Review by Frank Plowright

When she was very young Lucia Castillo adored her eccentric grandfather’s tall tales, which opened her imagination. He claimed to be a knight of old, protecting the innocent and helpless, and Lucia took on board his values about helping others. Unfortunately, the rest of the neighbourhood just considered her grandfather nuts.

Their view of Lucia also moves in that direction after a particularly disastrous day in which she wrecks the Mayor’s car when trying to help someone, then compounds the mistake by unintentionally throwing her friend Sandro under the bus. Not literally, you understand.

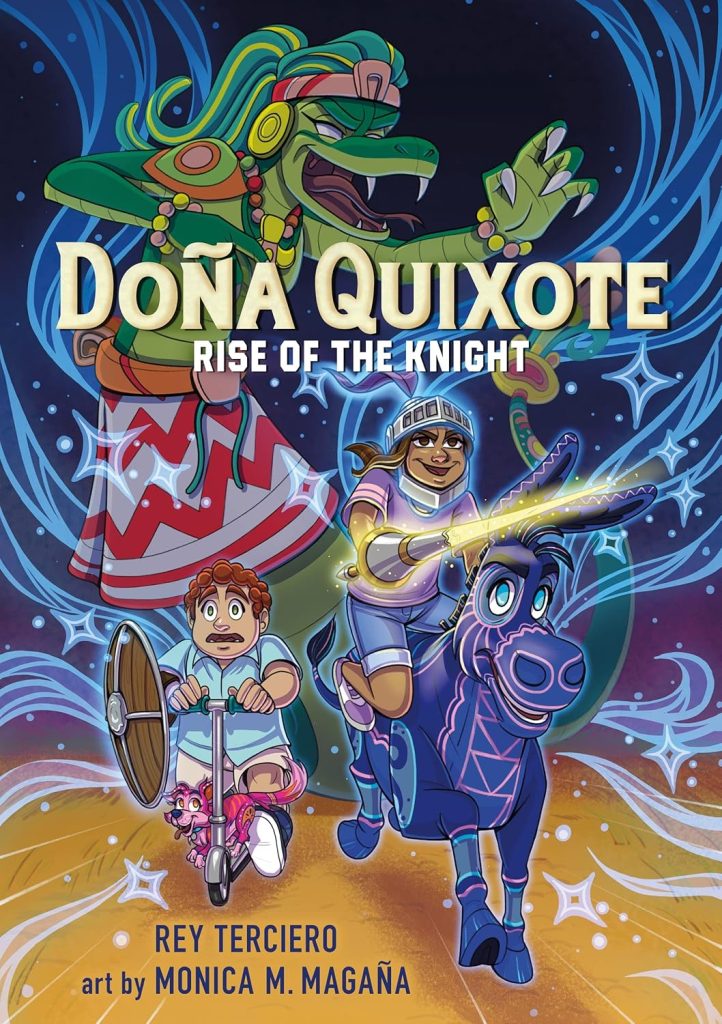

When completing the list of chores assigned to make up for her mistake, Lucia comes across an old helmet, shield and broken lance combination and learns she’s descended from history’s greatest kindly soul looking out for the helpless, Don Quixote. Putting on the helmet enables her to see a different, magical world, and it also reveals the reality of some locals. Contrasting that are real world problems, such as Lucia’s grandmother being an illegal immigrant.

Rey Terciero and Monica M. Magaña create an immediately friendly and inviting world based on ours, except featuring slight cartoon exaggeration. Rocky, the donkey Lucia’s grandfather bought her as a foal is the only real anomalous element, but then there are still horses kept on Dublin estates. Via dialogue, posture and expression Lucia is constantly likeable, and sympathies increase via Terciero’s plot being based on constant misunderstanding, with Lucia held responsible for what others can’t see. This being the case makes her relationship with Sandro all the more touching as he has faith despite not being able to see what she can. It’s a credible updating of Sancho Panza’s relationship with Don Quixote.

The reality of families where Spanish is the first language is recognised by frequent use of Spanish phrases, although none beyond the understanding of young readers given the way they’re used. They’ll quickly pick up abuelo and abuela as grandfather and grandmother, and the meaning of other phrases will filter in. Terciero gradually introduces Mexican myths, as supernatural entities, supplying some great stories even if all the creatures in Lucia’s book aren’t yet seen in the wider world. Some are, though, like the toenail eating duende, used to good effect.

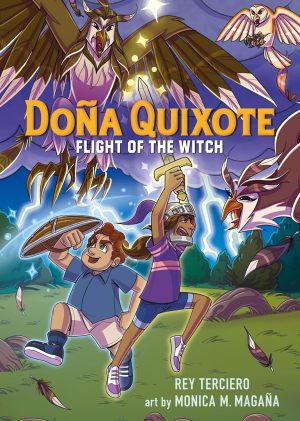

Rise of the Knight is cheery despite setbacks, and Lucia’s belief and persistence is a powerful engagement tool. Readers will be rooting for her to somehow combine her knowledge with a way to persuade her disbelieving mother that danger is imminent, and Magaña’s pages deliver the spectacular for the finale. All in all a solid all-ages read, and there’s more to come in Flight of the Witch.