Review by Ian Keogh

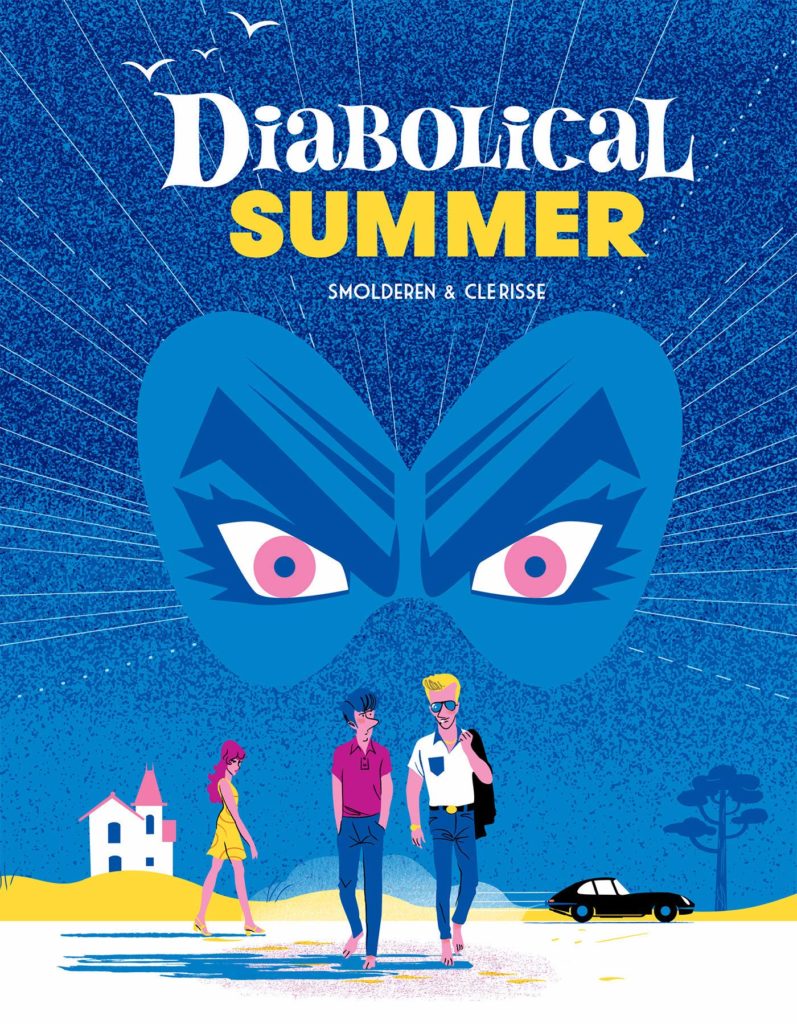

Moving forward a decade from the wonderfully stylised Atomic Empire, Thierry Smolderen and Alexandre Clérisse also switch genres. The cover suggests a spooky and mysterious horror story, yet Diabolical Summer doesn’t slot into any neat genre classification, the spy thriller being the closest while not covering everything. It’s an almost perfectly pitched story, art and revelation combining to intrigue and beguile.

As it opens, Antoine is competing in a tennis tournament, accompanied there by his father, after which a number of disturbing events occur, not least his father being approached by someone he knew years previously from the French Secret Service. His fifteen year old hormones jumping, Antoine is toyed with by nineteen year old American visitor Jean, and befriends his opponent from the tennis match, Erik, far more adventurous and possibly with his own agenda.

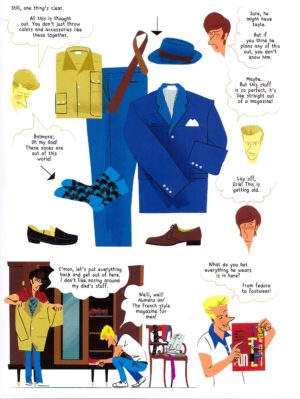

The trappings of the swinging sixties are supplied by Clérisse every bit as beautifully as he previously gave us the what’s now the retro-future of the 1950s. He seizes on the progressive design elements of the times, the stylish cars, the fashions, and James Bond, creating the art in a succession of flat panels, vividly coloured, using a twilight selection, the purple, dark red and dark blue setting the atmosphere so skilfully cultivated by Smolderen. Despite moments conflating Warhol prints, acid, the Kennedy assassination and Danger Diabolik, Clérisse’s refinement always prevents Diabolical Summer slipping into the parody that in some ways it is.

Having introduced a mystery about Antoine’s father, Smolderen then replaces him with the more worldly wise and boastful Erik as an alternative influence, but not before disclosing tantalising information about what will unfold via Antoine’s first person narrative captions. These provide a smouldering emotional backdrop to a singular coming of age story with the truth perpetually just beyond Antoine’s reach. Diabolical Summer, however, is a story in two parts. Antoine’s narrative is revealed to be taken from the book he wrote about events in 1985, and as that concludes readers will join some dots that he doesn’t, either from being too close or unwilling to believe. Smolderen has also supplied a convincing reason for Antoine to doubt some later events.

Antoine’s novel prompts further revelations, and more follow in 1990, opening new doors. Smolderen’s revelations are clever, as is the path he takes. There must have been a temptation to provide Antoine with a comforting closure, but that’s not achieved as Diabolical Summer eventually spans over forty years, going back as well as forward. What Antoine perceived in that late 1960s summer is revealed to the audience, if not always to him, the only disappointment being the big revelation for the finale is something sharper readers may have already figured out. Smolderen rescues that with a nice coda letting us know Antoine’s destined to remain tormented, just via a different source. It’s an appropriate downbeat ending to what’s been a compelling read.