Review by Frank Plowright

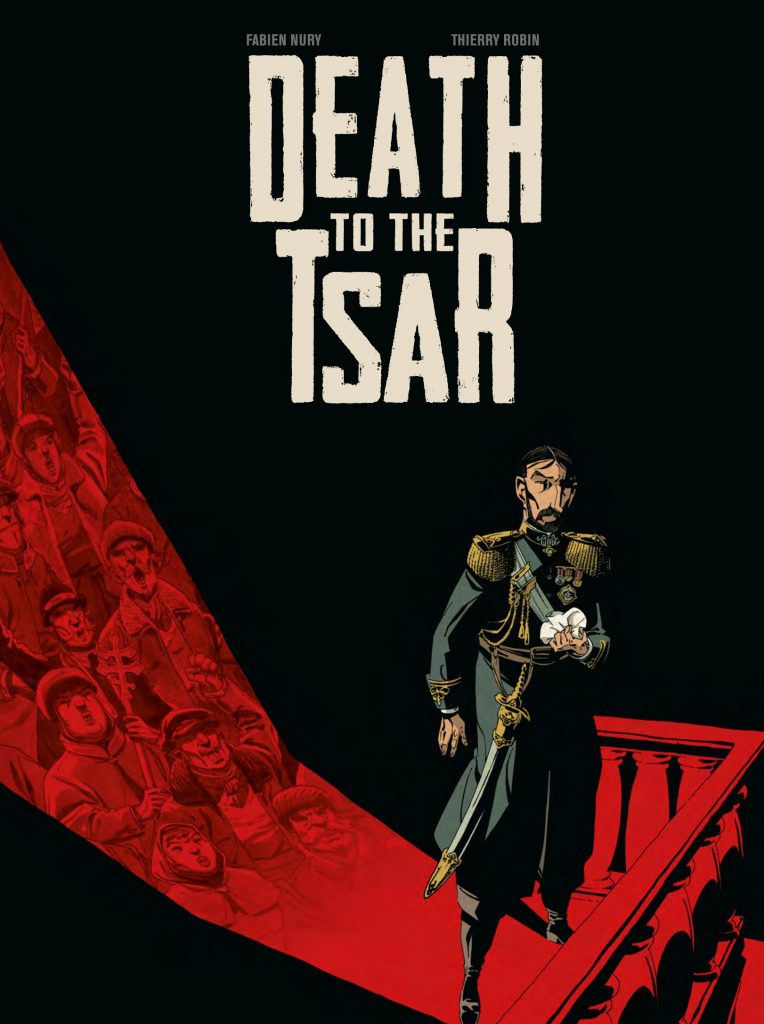

Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin’s Death of Stalin was a delight from start to finish, a dark black comedy about a person whose departure from the planet few genuinely mourned. Can they repeat the same trick dropping back a few decades and looking Sergei Alexandrovich, Governor of Moscow in 1904?

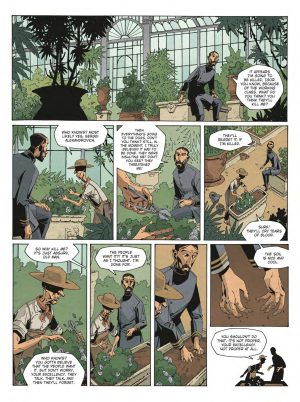

The title is a mystery, as Sergei is actually Tsar Nicholas’ Uncle, and the circumstance of the Tsar’s later death during the Russian Revolution remain in the future. Starting with the tragedy initiated by a handkerchief Nury and Robin stitch together a complex series of segues between scenes as Sergei goes about his daily routine puzzled about why people hate him. It’s actually more the system of privilege that he represents that the population have come to despise in times of hardship, the creators depicting Sergei himself as a bumbling idiot who’s been bred with expectations and can’t understand why those expectations aren’t met. While he’s entirely disconnected from the people he in effect rules, those in positions of power beneath him are aware of circumstances and reasons, and over the first half of a compelling character study, we become so. Sergei remains ignorant.

Having shown us Sergei’s life and trepidations, Nury switches focus for the second half of the graphic novel, now following the movements of Boris Aznikov, a committed revolutionary who’s survived an attempt to hang him. These movements occur over the same period as the first half of the book, and offer an alternative view of some scenes, revealing how they came about. Of interest is the opposition being depicted as well organised and well funded, not a random rabble. Boris, or Georgi as he’s popularly known, is a complex character, at times someone from a Dostoevsky tragedy and at others almost a James Bond of improbable escapes. It’s a neat trick comprehensively pulled off.

Robin’s meticulous cartooning ensures similarities between Death to the Tsar and The Death of Starlin, but they’re very different propositions. This is equally a confluence of atrocities, but there’s very little to laugh at, with just an occasional bleak joke punctuating what’s otherwise a study of two personalities of opposing ideologies. Far moreso than the Stalin story, Nury extrapolates around history, with Aznikov a creation representing an ideal rather than being an actual historical figure. The dramatisation is effective, but there’s also a feeling of playing fast and loose to achieve that dramatic effect, with the memorable aspect of the handkerchief contrived as a continuing motif without a historical basis.

Death to the Tsar is an immensely readable character study, but the greater element of fiction and missing humour render it a drier and marginally less compelling work than The Death of Stalin.