Review by Ian Keogh

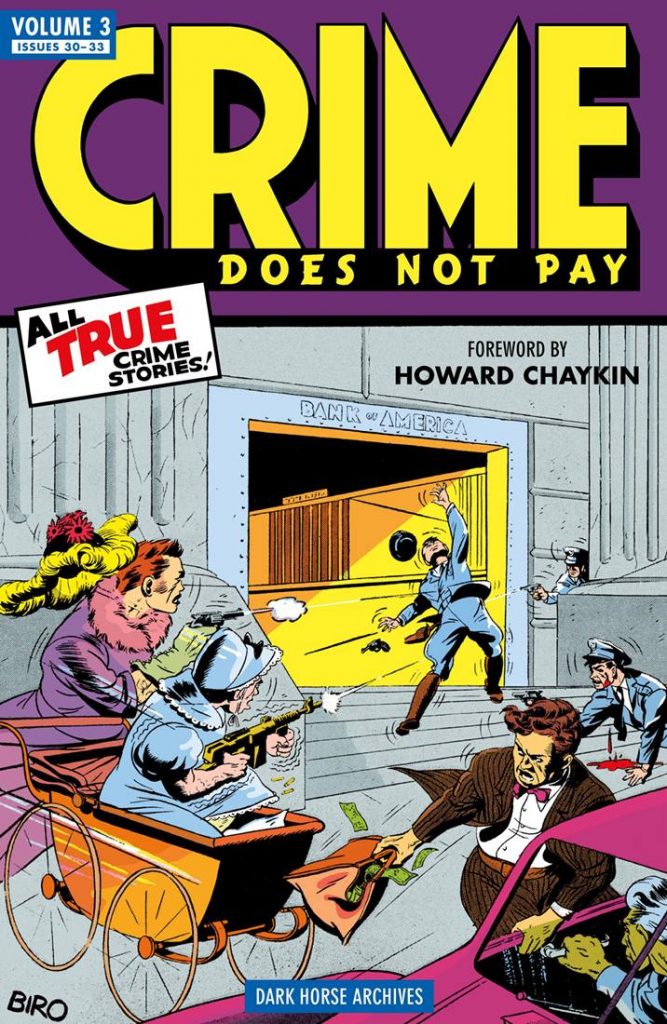

The luridly sensational cover shows that by 1943 any veneer of the hypocrisy ensuring the content managed anything other than the slightest nod to the title was rapidly slipping away. Unrefined in tone and execution, it’s utterly hilarious. So is some of the content within. Crime might not have paid by the final panel, but its exponents certainly had a ball of a time attempting to prove otherwise in these stories.

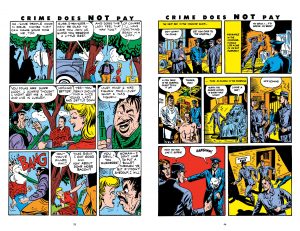

Howard Chaykin’s introduction notes that not only are these stories crude of intent, but they’re also crudely executed, with few of the artists any more than journeymen, and he suspects some of the more obscure names mask illustrators who’re hacking out the pages for a few extra bucks. He singles out Jack Cole and Dick Briefer as rising above. Despite Briefer’s standards slipping by the end, the editors obviously realise this, as by 1943 he’s allocated to two strips per outing (sample spread left), his ‘Whodunnit?’ feature closing each issue. As before, the inconsistent Jack Alderman (sample spread right) and Alan Mandel are the other standouts. Alderman’s story is unusual in writer Milton Kramer also being credited on a well designed splash page resembling a cinema poster. There’s very early art from Carmine Infantino, but it’s not great.

A selection of the usual gangster biographies feature, but while the gist of them is dramatised truth, there was no fact checking. Monk Eastman’s story has him a kid in 1900, when he was actually 25, and Jean Cavaillac’s notes that for “obvious” reasons the names of certain characters are fictitious. After that warning what should we make of the only character named in the entire story being Cavaillac himself? Could it be this entire “true”, but generic, story was made up? A later story also makes the point of using an alias, this time to “protect” a woman who’s seemingly happy enough to hang around with a couple of thugs who tell her they’re planning a robbery. However, just when a succession of vaguely named criminals like Marie of France and Nolan the Notorious have convinced every story is a figment of the writer’s imagination, a quick online search reveals there actually was an early 20th century serial killer with the unlikely name of Herman Mudgett. Court papers now available online also reveal the career of Farrington Hill, sentenced in 1943, as being much like Rudy Palais’ story, so the writers have to be given credit for honesty at least part of the time.

The bigger truth is that from a shocking enough start as seen in Vol. 1, the stories are becoming ever more violent and sensationalistic, the artists emphasising the shootings and other killings. That, though, is largely irrelevant as readers will come to wallow in the squalor as so luridly portrayed with unfettered joy.