Review by Frank Plowright

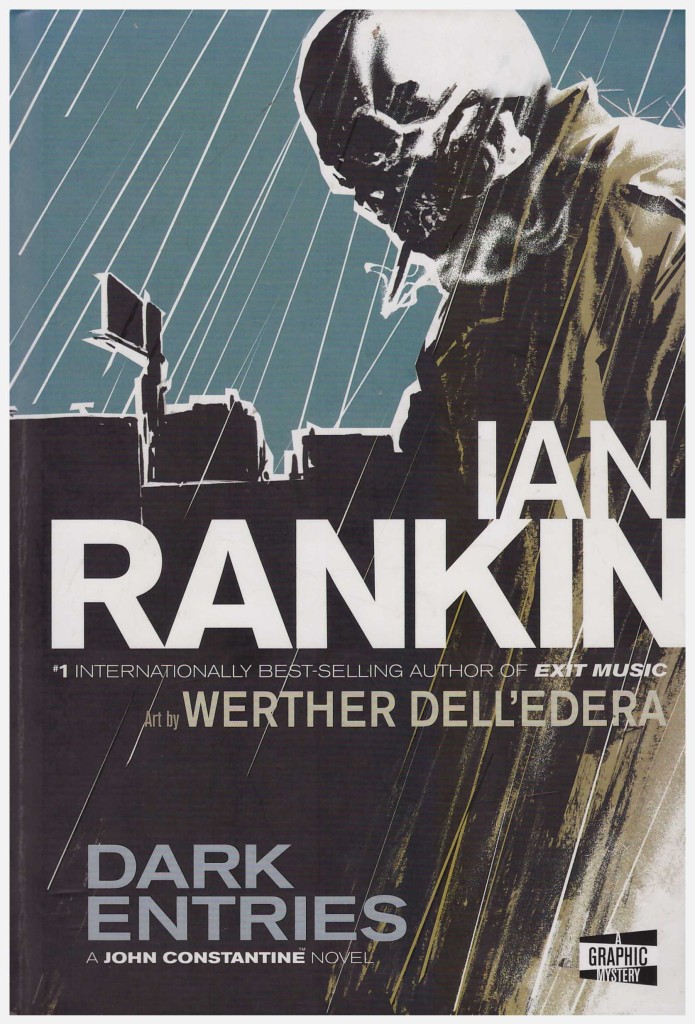

Acclaimed crime novelist Ian Rankin starts with a brilliant concept: stick John Constantine in the Big Brother household. It’s a natural, isn’t it?

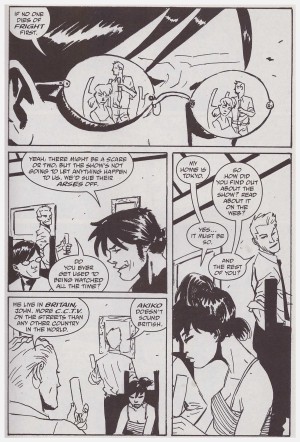

Constantine is visited at home by a TV producer who explains that his reality TV show in which a group of young people are locked in a house and filmed 24 hours a day is experiencing problems. The hook is that the volunteers are to be scared while in the house, but can escape via secret rooms and tunnels. The first week of the show, though, is for acclimatisation and introductory purposes only, yet the six contestants are each seeing a frightening manifestation invisible to the others. This is not CGI generated by the producers. The solution appears simple enough. Constantine should enter the house and work out what’s going wrong. With all the due paperwork and waivers signed, in he goes.

Although there have been Constantine stories that could also be categorised as crime, his milieu is horror or supernatural, and that’s what Dark Entries is. It therefore seems odd of Vertigo to launch their black and white pocket-sized crime series with Constantine, even if Rankin is known for his crime stories. It transpires that Rankin isn’t very interested in crime this time.

Having supplied a great concept, it seems for a long time as if Rankin then doesn’t know where to take the plot. Around half way through, Constantine arrives at a conclusion, and the mood changes rapidly, indicated by the rather neat split of the previous material being printed on white bordered pages while it’s black borders for the remainder. Astute readers are likely to figure out most of what’s going on well before the big revelation, and from there it develops into a slightly more clever version of a teenage slasher movie.

Italian artist Werther Dell’Edera is competent enough to illustrate a story relying on talking heads for a significant percentage of the page count, but not special enough to prevent this from looking dull. This is partly because, beyond a good splash page, he doesn’t move beyond a minimum of four panels per page, and he often swamps his faces in shadow for no good reason. On the positive side, his cast is easily distinguished.

There are decent elements, the way Rankin works out connections his plot requires, for instance, but by and large there’s nowhere near the invention and compelling suspense that characterises his novels.