Review by Frank Plowright

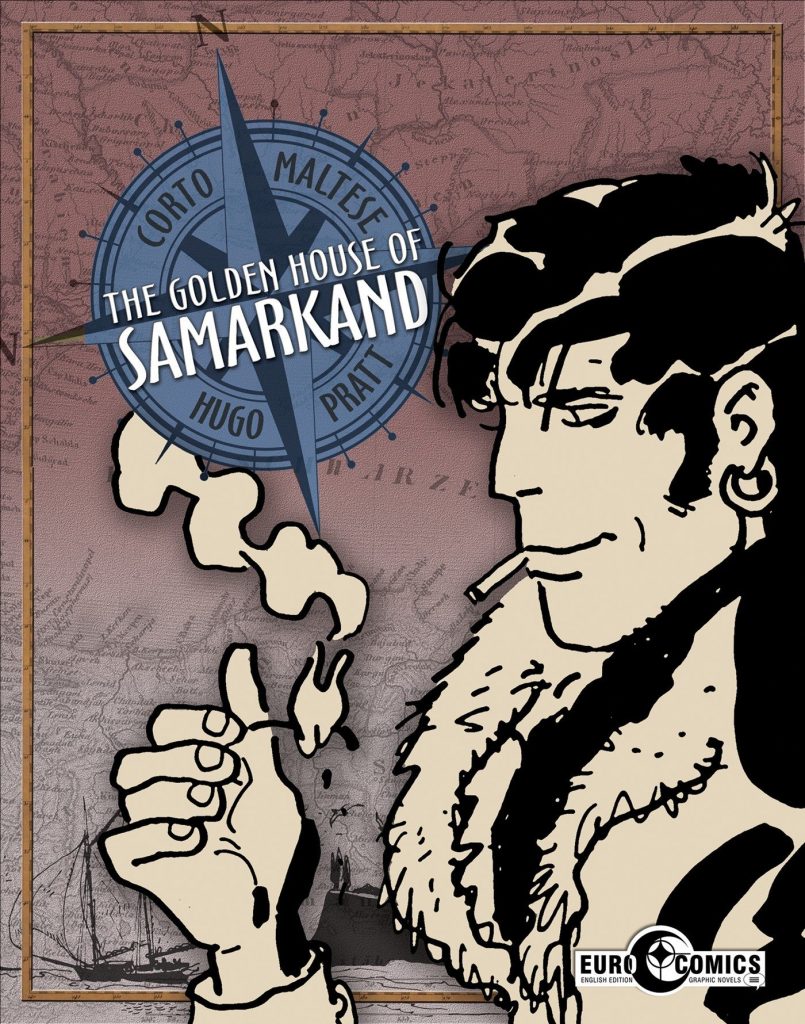

No-one has ever created a synthesis of languid adventure and atmospheric personalities that comes anywhere close to Corto Maltese, and a consistently delightful aspect is how Corto himself just drifts into trouble. It’s a matter he ponders briefly midway through. Investigating a rooftop location at night, his problems begin in Rhodes when he’s mistaken for someone else by a Turkish group who consider themselves patriots. As ever, Hugo Pratt weaves historical turbulence around Corto, who’d rather distance himself from any cause. This becomes more difficult as other incidents involving his doppelganger affect his ability to operate anonymously. The doppelganger is hardly an original story device, but Pratt’s use of it is thoughtfully applied as we hear of Chevket from several sources, all considering him a dangerous man.

Corto arrives in the troubled intersection of Armenia, Persia, Russia and Turkey due to something found in Fable of Venice, prompting a journey with two purposes. One we learn at the start, the other soon after, but just how did Corto know his sometime ally Rasputin was imprisoned? Rasputin isn’t the only character making a return from earlier adventures, but he’s the most significant, his spirit seemingly free to roam despite confinement. Pratt was never shy of spiritual content, an acknowledgement that Western society hasn’t yet learned all there is to know, and an early sequence has a form of dream contact between Corto and Rasputin.

While Pratt at this stage of his career is no longer using chapter separations for Corto Maltese, there’s still an episodic structure to The Golden House of Samarkand, distinct places where the location or style shifts radically. Almost as a game, Pratt introduces one figure of historical importance after another, mostly in small cameo roles, but all in Corto’s orbit. The struggles against which the story plays out would result in the modernisation of Turkey, looking westward for influence, but the constant flux of allegiances, both personal and military, ensure uncertainty prevails. The complexity has its modern day equivalent in Syria.

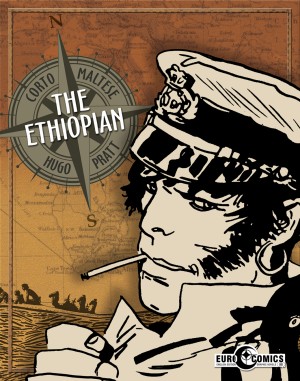

The art is glorious. Loose, yet evocative and often shadowy figures populate a well realised world. Pratt loves machinery, so this is always fully detailed, but the wonder of some other backgrounds is that it’s not until pausing to focus on them that it’s obvious how simple their construction is. Both Gilbert Hernandez and Alex Toth work in the same way, deceiving with a few squiggles and a few lines. As drawn by Pratt, Corto himself is always impassive, deliberately enigmatic, but other people ooze personality, with Rasputin topping the list, his trousers becoming ever baggier as the story continues.

A slight problem with The Golden House of Samarkand is much is too whimsical. Rasputin’s self-serving cynicism is funny, and we’re used to the enigma of Corto, but apply random motives to too many others and the construction begins to weaken. Marianne floats through scenes unless a shock is required, and is there a purpose to the presence of another woman? Balancing that are fine scenes of quiet reflection and profundity, considering the poetry of clouds for one, and a wonderfully maintained sense of the ground constantly shifting. The complexity ensures this isn’t the ideal introduction to Corto Maltese as there’s a dependence on understanding the world of magical realism Pratt’s established for Corto, as otherwise the anchor is sometimes missing.

All EuroComics Corto Maltese editions present Pratt’s work at its best, in large format on thick, bright paper stock that defines the art. Pratt next looks in on Corto in Argentina two years after these events with Tango.