Review by Woodrow Phoenix

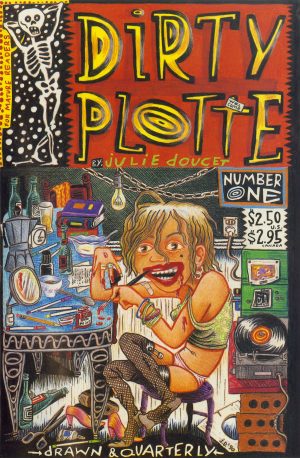

Julie Doucet’s fiercely brilliant Dirty Plotte series lit a fire under alternative comics in the 1990s that still smoulders today in the fingers of hundreds of creators. A restless, always experimenting force, she was determined to avoid being “stuck with the cartoonist label for the rest of my life” and quit drawing comics in 2000 to move onto other styles in other artforms: engraving, printmaking, linocuts, collage, sculpture and animation. She has since published books featuring her explorations in various mixed media: Lady Pep; Long Time Relationship and a visual journal, 365 Days.

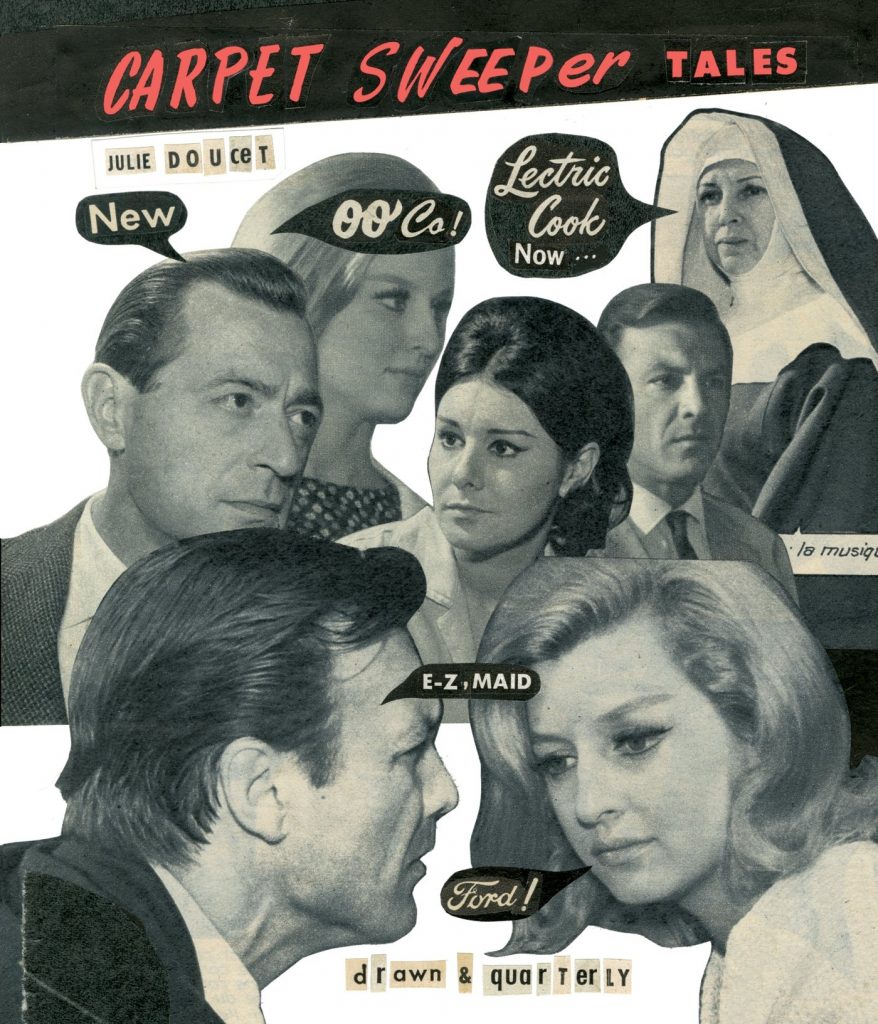

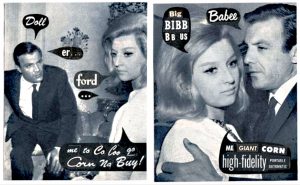

With Carpet Sweeper Tales, Doucet makes a kind of return to comics, combining her interest in found materials and collage with narratives more cryptic than her previous work. From working with old magazines and making montages that contained words, Doucet became interested in creating cut-up poetry, initially in German because, as she explains in an interview in the collected Dirty Plotte: “You’re less self-conscious when you work in another language. It’s difficult in French because everything has to be perfect. You have much more room to manoeuvre when you write in another language.” After finding piles of old Italian photo comics – called fumetti – from the 1960s, she began cutting out the images that interested her and adding text constructed from other magazines she’d assembled previously. “I also wanted to do something phonetic. And I wanted it to have meaning but not too much. I wanted the reader to have to work hard to find something else. You really have to read it out loud for it to make any sense at all.”

The narratives derived from this process are more like incidents than stories, images of men and women mostly travelling in cars, or staring moodily at each other in nondescript locations, speaking nonsensical dialogue made from ads, captions, headlines and sometimes just strings of punctuation marks. It seems pointless at first but if you do read it aloud as advised, rhythm makes the phrases begin to cohere. There is a line you can draw from Dirty Plotte to these cut-ups that feel like an alternate expression of the emotions driving her earlier comics, but these are a lot less forthcoming. You could just entertain yourself with trying to figure out which images come from which of the Italian fumetti sources she lists at the front of the book, including The Knocked Over Flower (1962), Young People Can Love Too (1965), and I Was Helpless (1966), and which are from old American magazines Better Homes and Gardens (1948-58), Mechanix Illustrated (1963-64),and Needlework & Crafts (1968-70).

Carpet Sweeper Tales is definitely not for everybody. It’s a beautifully designed book, the squarish shape feels nice to hold and the images are attractive and amusing in themselves with their odd array of balloon shapes and text styles, but readers looking for the familiar old Doucet style will find nothing here to reward their attention. If willing to go along with the experiment you may find these assemblages surprisingly entertaining.