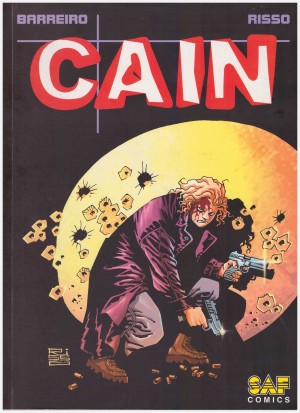

Review by Frank Plowright

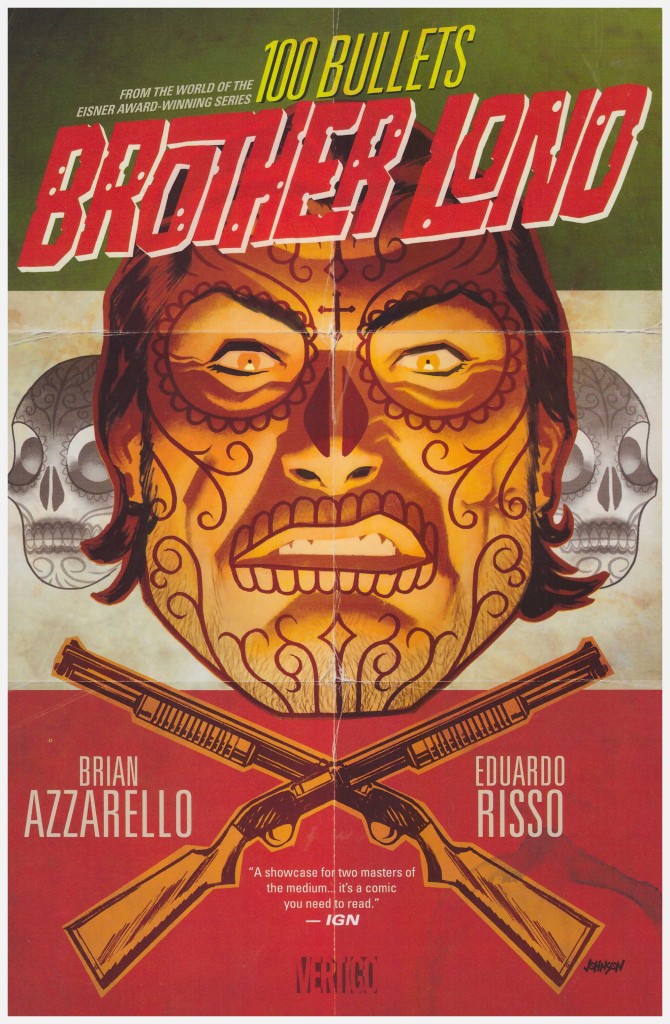

Five years after they wound up the stunning 100 Bullets, Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso reunited for a spotlight on that series’ most popular character. Lono was like a bulkier Wolverine, big, but not the biggest guy on the block, and a scrapper who never quit, with a high tolerance for pain and injury. He revelled in what he was, yet while he could bury his psychotic tendencies for a while, there was scant warning of that facet of his character breaking out, and little regret when it did. The only snag regarding him starring in a new graphic novel was that he’d perished in the bloodbath that concluded 100 Bullets. Apparently not.

Three years prior to the opening pages a giant of a man staggered into a confessional in Durango, Mexico. The man who emerged remained in one of Mexico’s most dangerous cities, among the drugs and deprivation, living in the church’s vastly overpopulated orphanage. As he notes, his most dangerous enemy is himself, so he keeps his head down, his nose clean and his fists open. He claims to remember nothing of his past beyond his name.

Lono’s not quite the Man with no Name, but Azzarello is playing a familiar tune in a stylish manner. The quiet loner that eventually breaks loose with catastrophic consequences is a fiction icon, so what will tip him over into his inevitable old testament retribution? The surrounding atrocities are catalogued in appalling fashion, so there’s plenty of choice. That, though, is the smart double-edged sword when this card is played. What for the reader or viewer is catharsis is damnation for the protagonist.

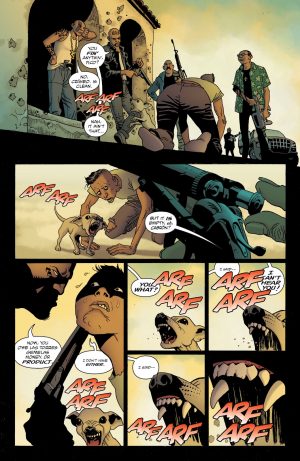

A moral quandry was prominent in all the best 100 Bullets material, and a further question in play here is whether or not you can truly suppress who you are. Azzarello signposts other elements of his narrative, but with a knowing wink, and surely no-one will be surprised at the outcome. It’s that lack of surprise, though, that renders Brother Lono a weaker work than 100 Bullets. We head from A to Z, although the distance is possibly greater than required, with precious little intrigue, a sense of inevitability, and an almost caricatured villain. On the plus side, the dogs of Durango are no more likely to survive than those seen in the previous series.

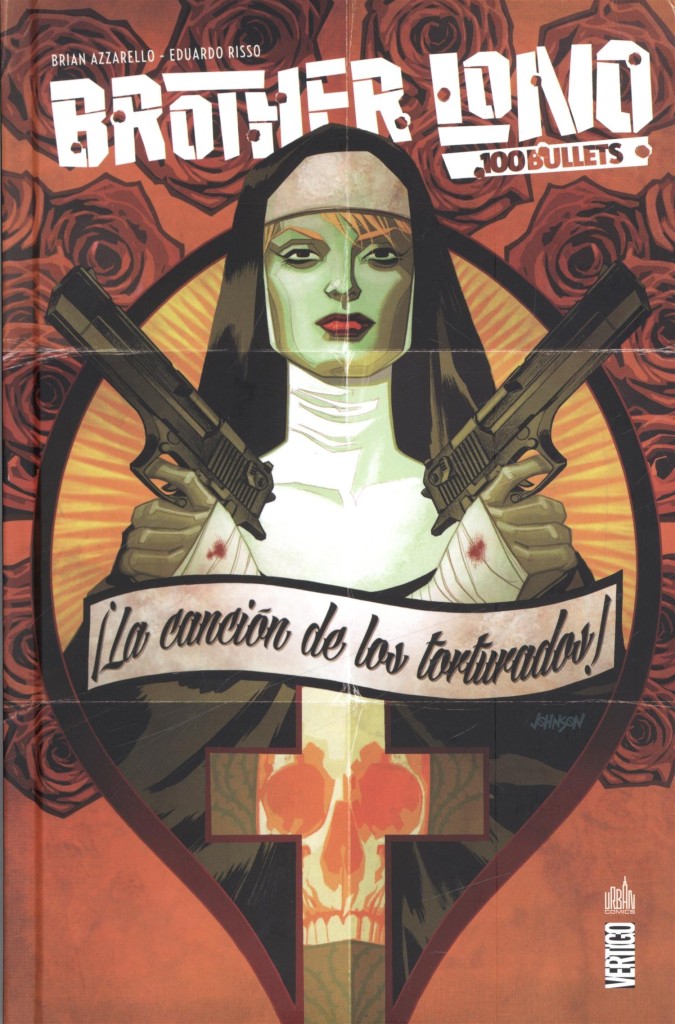

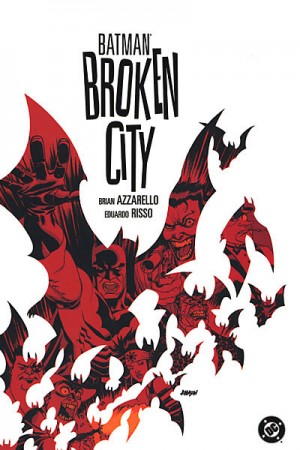

If Eduardo Risso’s ever turned out a bad page of art it was long before he was seen in the USA. He’s asked to be more graphic than previously (or perhaps that was his choice), but the effect is to weaken the plot by underlining it. That’s also the case with regard to one of the character designs, which is too obvious.

If Azzarello and Risso didn’t have such a fine track record this would be decent enough, but as it is, it comes across as half-hearted.