Review by Graham Johnstone

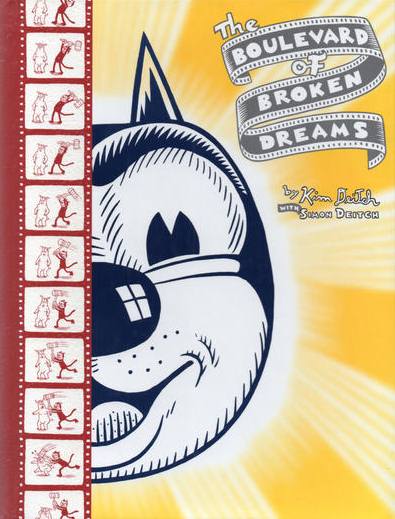

Boulevard of Broken Dreams is a fictionalised glimpse behind the scenes of animation in the USA – from its beginnings to the boom years, and beyond. It’s a compelling story of troubled lives, overlapping love triangles, tragedy, and, yes, broken dreams.

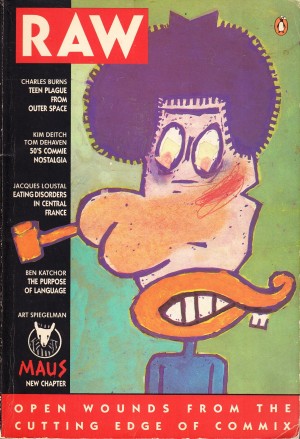

The title chapter was first published in Raw, and Kim Deitch is arguably the precursor of the younger Americans who appeared there. He’s born from American popular culture, yet has an ironic, analytical take on it. With his precise compositions, stylishly simplified figures, and razor-sharp brush lines, he pre-empted both the content and style of Charles Burns.

It begins with a hand lettered and illustrated introduction, explaining how the author was brought by his father to the animation studio he ran. Deitch is indeed the son of an animator – the lauded Gene Deitch – but fact and fiction, reality and delusion are already starting to merge.

The story proper begins in 1927, with fictional animation pioneer Winsor Newton delivering one of his animation with live action vaudeville shows – just as the real life Winsor McCay did. Watching this are animation studio boss Fred Fontaine, his production manager Al Mishkin, and the latter’s talented but troubled brother Ted. We also meet two female animators: Lillian, subject of Ted’s mostly innocent fantasies, and Reba, plucked from the production line to be Mrs Fred Fontaine. Each will unfortunately trigger breakdowns for the vulnerable Ted. Always at the scene of trouble is Dietch’s Waldo the cat – here he’s both the subject of Fontaine Fables’ increasingly saccharine films, and the supernatural or imaginary ‘friend’ of Ted and later his nephew Nate Mishkin.

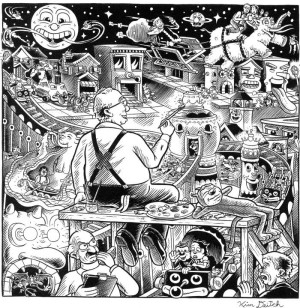

An intricate and hallucinatory double page spread of a cartoon theme park introduces ‘The Mishkin File’. It’s the notes of the psychiatrist at Berndale Acres, where Ted is a recurring inmate. The image, we’re told is from a set of murals he’s asked Ted to paint as a form of therapy, exploring his complex relationship with Waldo.

Always in the backdrop, is the fictionalised, but essentially true history of animation in the USA: the pioneering work of McCay/Newton; the juggernaut of Disney, and the pressure on rivals to produce similar material. Come World War II there’s the upbeat propaganda, as the heroic Rocket Rat thwarts Waldo and the Nazis. We see the politics through Lillian’s story – she works on experimental films, supports the Disney workers strike, is caught in the anti-‘communist’ hysteria and is blacklisted. The Gene Deitch figure in the story seems to be Bert Simon, Fontaine’s liberal new manager, who rates Lillian and applauds her standing up to the notorious Un-American Activities commission.

The final section ‘Waldo World’ is set in the 1990s, when the surviving characters reconnect at the launch of a line of Fontaine inspired ‘Lil’ Critters’ toys. They discuss the old days, with a series of flashbacks that elegantly complete the jigsaw. In the 1950s scene much of the gossip is of business matters, in particular Newton and Fontaine’s idea for a cartoon theme park – Waldo World. The loose-tongued Ted lets this slip to ‘a bigshot’. “This guy had the nerve,’ reflects Waldo, “to take our idea, and name it after himself!”.

It’s a fascinating story, brilliantly told, and full of vivid, telling details. Deitch’s artwork effortlessly conveys everything – from a row of artists drawing different moments of a scene, to rooms cluttered with memorabilia. The usual razor-sharp rendering slips occasionally – perhaps brother Simon, assisting here, can’t match Kim’s decades-honed technique.

Boulevard of Broken Dreams was included in Time Magazine’s list of the 100 best English language graphic novels.