Review by Ian Keogh

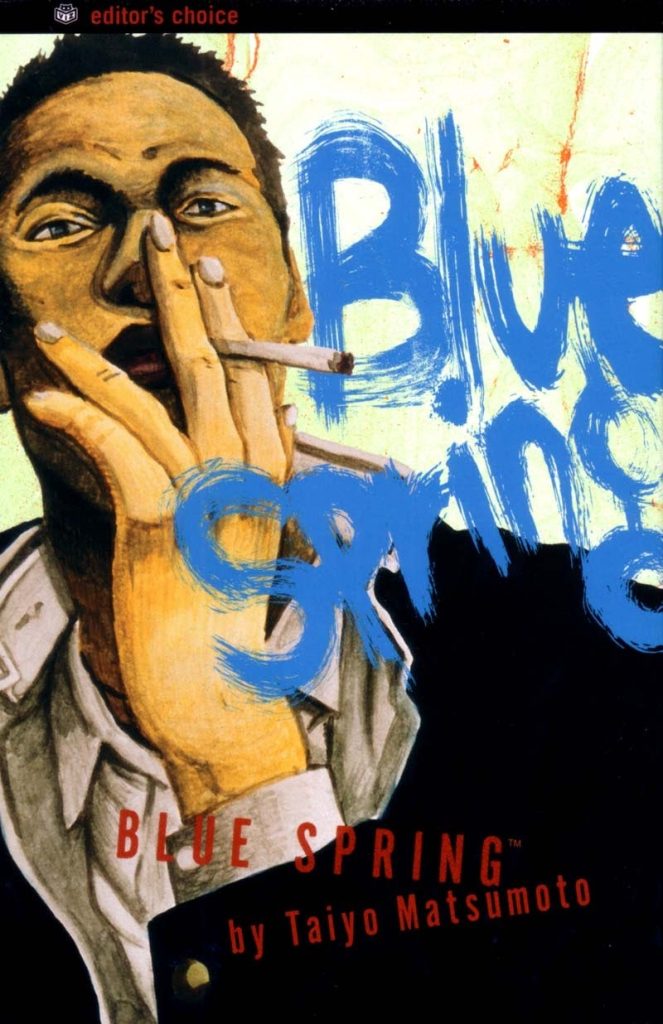

Blue Spring is a drama told over individual chapters following Kujo, the edgy high school kid everyone else looks up to. He’s on the verge of leaving school, which can’t happen soon enough as far as the staff are concerned, and a selection of short stories follow him and his gang around as they try to fill pointless days in a decaying neighbourhood.

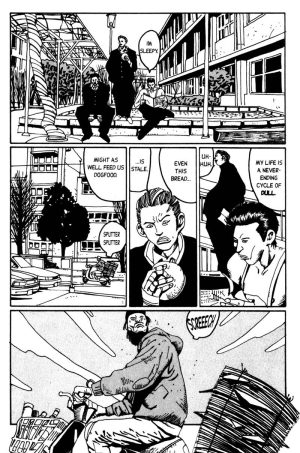

Compared with most manga translated into English by 2004, Blue Spring was surely groundbreaking. Despite an exaggerated form of art, it’s rooted in reality, and there’s an allure about Kujo and his nihilistic lifestyle, certainly one that captivated Taiyo Matsumoto when observing the real life equivalents he used as models, as revealed in his notes. He elevates a mystique via stylistic touches such as redacted eyes in the opening story. Another is the universal graffiti surrounding Kujo, although that loses some effect for non-Japanese readers by being translated via asterisk and footnote. Matsumoto almost acts as a documentary maker taking a naturalistic approach in just following Kujo and his gang around as they shoot the breeze, cause trouble, and avoid the police.

For all the commitment to realism, the storytelling isn’t always straightforward. There are the occasional moments of confusion as Matsumoto slips into Kujo’s power fantasies, but for the most part realism is the order of the day. It’s not immediately apparent, but that also applies to a story where the guys are playing mah-johnng, but their minds are on a baseball game and why it was lost. The experimentation is most extreme on the penultimate story, when jaggedly cut panels slip into each other as Matsumoto follows multiple narratives starting with a restaurant bill being short. It’s violent, absurd and complex.

Spread over three chapters, ‘Revolver’ is the longest story, credited to Caribu Marley, an alias for Garon Tsuchiya, best known as writer of Old Boy. Kujo and his gang are given a map to a location where they find a gun with three bullets. What will they do with it? As the sensationalism of Blue Spring doesn’t encompass a leap into crime fiction, Kujo’s plans are distinctly bereft of ambition, which makes ‘Revolver’ stand out. It’s not a springboard for anything other than messing about, but the way Matsumoto tells the story there’s a constant suspense generated by the theme of Kujo being a danger to himself and others.

Anyone expecting the refined artwork now associated with Matsumoto is going to be surprised by the pulp aesthetic applied here. It’s heavy on black outlines and close-ups.

The documentary following of largely aimless lives isn’t going to appeal to everyone. This isn’t the storytelling of set-up, mystery and reveal, and the characterisation is applied to a group rather than individuals, and even then the only real motivation is briefly dispelling boredom. Buy into that and there’s power to Blue Spring, but you could also find it as dull as Kujo’s day to day life.