Review by Ian Keogh

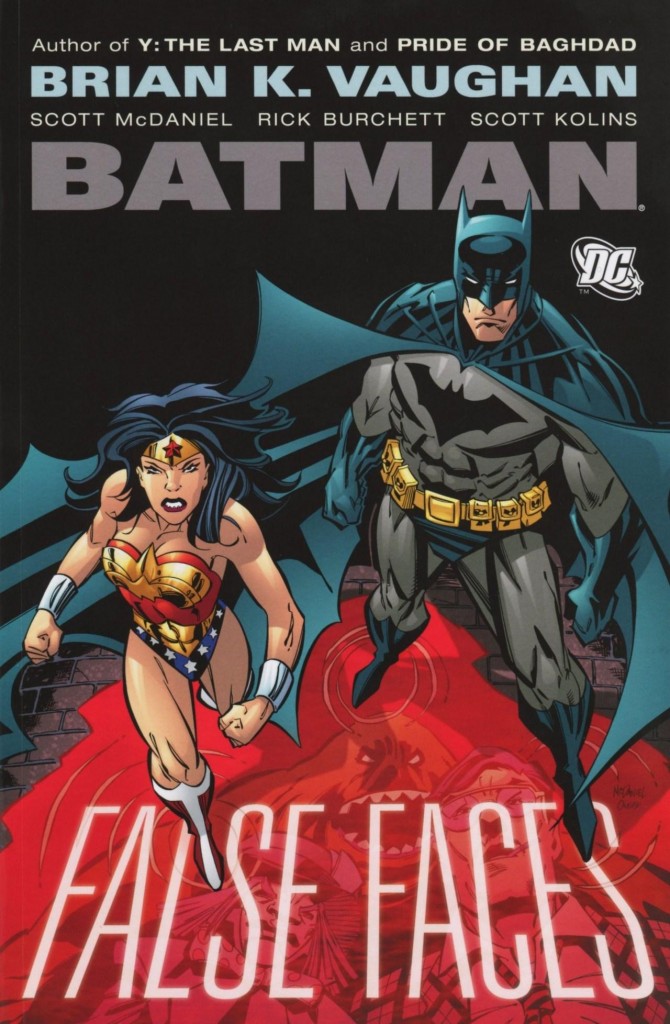

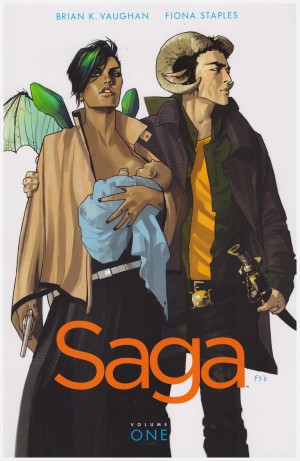

Brian K. Vaughan’s reputation as a comics writer rests far more on the series he’s generated than the relatively slim amount of superhero work he compiled beforehand. This collection is pretty much the entirety of that genre output for DC, who compromised when issuing a graphic novel under Batman’s name by including a two-part Wonder Woman story in which Batman is absent.

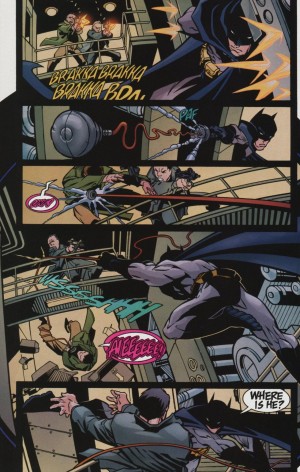

As Vaughan notes in his introduction and as the title indicates, identity is a common theme, and it first arises in the opening tale, which provides a surprise for readers already aware of Matches Malone and his purpose. To say any more would ruin matters for those unaware of the character, but suffice to say Vaughan uses the story to take a novel look at Batman early in his career. That it’s early in his career also affects Vaughan, as too much of the story is lengthy explanations, and the writer he became would compress this tale considerably. Identity is also explored via the villain of the piece, Scarface, accompanied as ever by the Ventriloquist. Artist Scott McDaniel (sample page) rarely draws a full figure, and when he does there are problems, as per a poor depiction of Barbara Gordon in her wheelchair, but when he has Batman swinging into action he’s just fine. The result is an okay Batman story, but people may have problems with the underlying issue, which is contrived to fit the plot.

Vaughan uses the Mad Hatter in his next piece, which turns on an interesting idea, but that’s the only remarkable element of the writing. Rick Burchett’s art is the stronger portion of the collaboration, at times almost veering into the 1990s animated version of Batman. Nothing wrong with that.

The Wonder Woman story provides the collection’s highlight, which has to be a first for a Batman graphic novel. Not only is there a fine art job from Scott Kolins, but Vaughan’s plot has a logically clever basis, makes good use of Wonder Woman and conceals multiple surprises. What’s excellent about the latter is that it’s with the same trick, brilliantly conceived every time. In his introduction Vaughan notes this as the earliest story included, and considers it the least developed. He’s wrong. It says what needs to be said, entertains and doesn’t overstay its welcome.

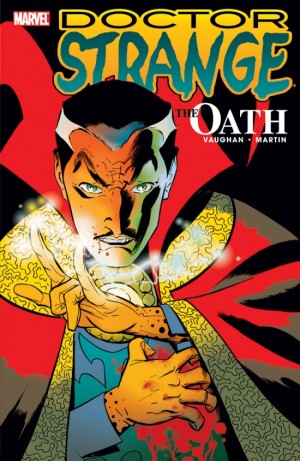

A sort of hidden bonus track is provided right at the end with the introduction of a new villain that no other writer picked up on, although Jeph Loeb was interested enough to expand on one aspect for the later Hush. Vaughan’s story is again neat, if a little wordy, and Marcos Martin’s art is exemplary.

Vaughan’s reputation is now such that DC knew they could sell this collection, but none of it is essential, and you’d be better off looking out his later work.