Review by Frank Plowright

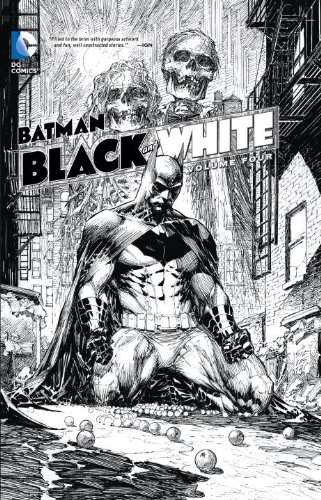

This collection of short, one-off Batman stories in black and white dips below the quality threshold set by previous volumes. Is this just a reflection of more conservative times, or just of the creators involved?

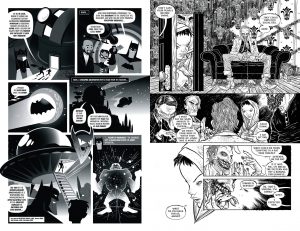

It’s not for want of top talents among the artists on display, which has always been the greatest strength of the series. Mike Allred, Lee Bermejo, Dave Bullock, Cliff Chiang, Michael Cho, Adam Hughes, Rian Hughes (sample left), Dave Johnson, J. G. Jones, Sean Murphy, Javier Pulido, Paolo Rivera, Andrew Robinson Kenneth Rocafort, Chris Samnee, Dave Taylor and Chris Weston deliver 136 pages of quality between them and that’s half the book.

The art is something to look at again and again, but the problem is the writing. There’s little imagination on display, with most of the strips having nothing to say that can’t be found in regular Batman titles, with few plots providing material that bears re-reading. Rian Hughes pushes the boat out, with a madcap tale of narrative structure and aliens. Keith Giffen themes his story, effectively illustrated by Pulido, around Batman striking fear into the heart of evil-doers, and Jimmy Palmiotti hits the charm button as Robinson portrays his story about a guy attempting to do the right thing. Marv Wolfman’s tale of ‘An Innocent Man’ packs a surprise ending, but Riccardo Burchielli’s Batman is so deep in shadow he’s barely visible.

Batman: Black and White has also been notable for an experimental tone, yet, good as most are, the artists all pretty well play to type, so it’s left to less familiar names to startle. It’s fair to say Damion Scott’s street art stylings are divisive, and the removal of the vivid colour he usually applies strips his art of much appeal. It’s Brazilian artist Rafael Grampá who provides the most astonishing interpretation of DC’s iconic Dark Knight (sample right). There’s a creepy quality to his stylised cast: a sweaty Alfred, a Joker with all teeth visible even with his mouth closed, and a Batman whose sweeping costume rumples around him. In a book with a fair percentage of great art Grampá’s work is disturbingly memorable.

After their absence in volume three, it’s pleasing to see biographical credits restored.