Review by Graham Johnstone

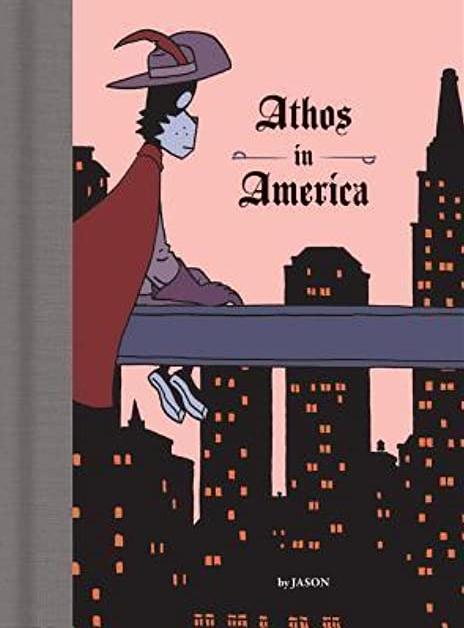

Athos in America is a collection of six short but concentrated stories by Norwegian John Arne Sæterøy, better known as Jason.

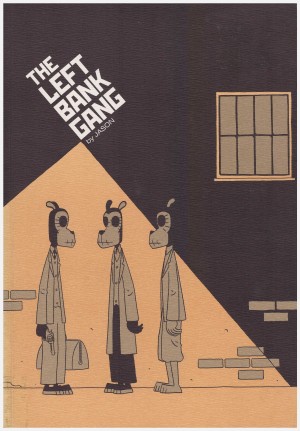

His anthropomorphic dogs, cats and birds are instantly recognisable. The drawing looks like a simplified version of Hergé’s ligne clair style, with suitably flat but subtle colouring. Different stories and scenes each have a distinctive palette.

Few people, though, will be buying this for the art alone. Jason is an intriguing writer, drawing on other cultural works, yet invariably adding his own character stories. If this were prose, we’d probably call these vignettes. They’re brief glimpses into lives – telling moments that hint at bigger stories.

For example, ‘A Cat from Heaven’ begins with a dog drawing comics. He’s being shouted at by someone out of the panel – the cat, and she’s leaving him. We don’t know what’s led to this moment, but the events that follow, quickly shift our sympathies to the cat. The dog turns out to be called ‘Jason’, so this is presumably about a real relationship. If so, it’s a brave, unflinching portrait of him at his worst. After the split, he pursues the cat to her mothers to carry on berating her. He’s arrogant about his work and casually dismissive of aspiring creators. It’s reminiscent of Joe Matt, who writes about his every vain, selfish, petty and deceitful act so frankly that we can credit the author with more maturity and sensitivity than his on-page persona.

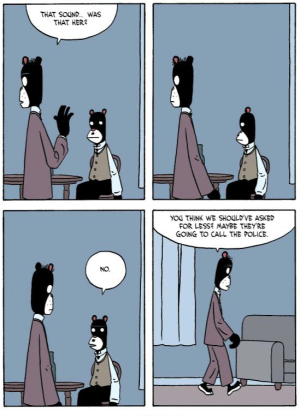

‘The Smiling Horse’ (pictured) similarly, drops us into the middle of something. Two guys are in a room waiting, we find out, on a call. The scenario, together with the lack of exposition, silent acting and minimal dialogue, is reminiscent of Waiting for Godot. Jason would reference that Samuel Beckett play explicitly in his next collection If You Steal. As we read on, we find out we’re in the endgame of a crime – it mostly happened off-stage, but we arrive just in time for the consequences.

The title story follows Alexandre Dumas’ famous Musketeer, alone and out-of-place in the USA. It surely reflects Jason’s own experience as a European, living in the States. References to other creators and their work, though, are more cryptic.

‘The Brain that Wouldn’t Virginia Woolf’ is at least the third work of fiction to reference this pioneering author in the title. This time the woman shouting at the man in the next room is a disembodied head: “Go out and get me a body! Someone young this time… Not some old wreck!” Several pages are split between them separately ruminating on their situation, then we move forwards and backwards in time to see both how it resolves, and what happened to her in the first place. There’s a mean, sardonic humour here: “A girlfriend with no body but a big mouth! Can I choose them or what?” Maybe he thinks Virginia Woolf, as a writer of the internal world might flourish as a disembodied head in a room, so why (he’s devilishly asking), can’t this woman!

‘Tom Waits on the Moon’ separately follows four struggling characters – perhaps that’s the link with singer-songwriter Waits? It takes a drastic, and exaggeratedly contrived, incident to bring them into the same panel. It ends there, and we’re left to imagine if and how they might further connect with each other. Jason’s skill, to borrow a phrase from Samuel Beckett, is to “[leave] out as much as he can.”

You can read these stories quickly, but you can come back to them often.