Review by Karl Verhoven

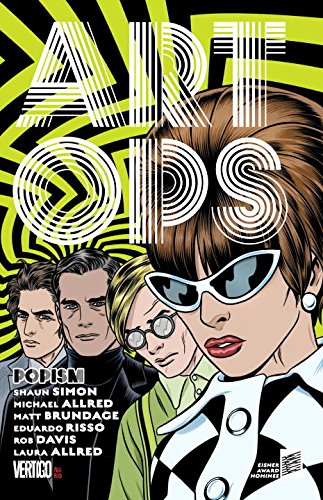

At the conclusion of How to Start a Riot Reggie Riot’s previously missing father reappeared deciding some bonding time was long overdue. Danny Doll once headed the Art Ops organisation, protecting the living art from theft, damage and destruction, but his was an eccentric form of guardianship as seen in the opening ‘Modern Love’, ironically titled as it’s set in the 1970s. Its two chapters pretty well disclose the background to everything previously seen. It reveals why there was a schism between Reggie’s parents, why Danny no longer runs the Art Ops, and what went wrong. It’s also a statement about art, about how it must be free to evolve and a plea that creativity can’t be shackled by possible consequences. As Shaun Simon’s already proved a knowing writer, he’s presumably well aware of the irony of this being expounded in what was originally a monthly serialised comic produced to deadline necessitating a replacement artist.

When that artist is as talented as Eduardo Risso there can be no real complaints, and for someone known for his shadowy realism he adapts extremely well to a surreal world in which art comes to life. However, the tone of Art Ops has already been set by Matt Brundage pencilling in the style of Michael Allred, with Allred applying the inks to ensure that’s the case, and it’s more effective over the remainder of Popism. For comparison purposes Allred draws the concluding chapter alone.

Two plot threads predominate, that of Reggie becoming involved in his father’s plans – “I’m asking you to bring scared, homeless and lost art here to me where I can provide a safe haven” – and the Body attempting to forge his way as a Hollywood screenwriter. Whereas most of the previous book concentrated on fine art, Simon now expands his plot to encompass many other forms of art from film to the written word, and in doing so diffuses any glue holding events together. In this world anything can happen just because it can happen, and it does. This makes for a stimulating plot in one respect and a tiresome one in another, where any idea that occurs can be thrown in without requiring any logic or explanation, because, hey, creative freedom is the truth of art. The deliberate satirical aspects are lost in the morass. The ending, however, is surprisingly conventional.

All this rather surprisingly leaves a fill-in chapter drawn by Rob Davis as the best in the book. Davis employs slightly out of kilter narrative techniques in his own work, and here illustrates a tale of necessity restricted to a single chapter with Reggie, the Body and J. Gorgeous investigating a series of murders. It says what’s needed briefly without justification or embellishment, and is an indication of what Art Ops could have been with greater discipline.