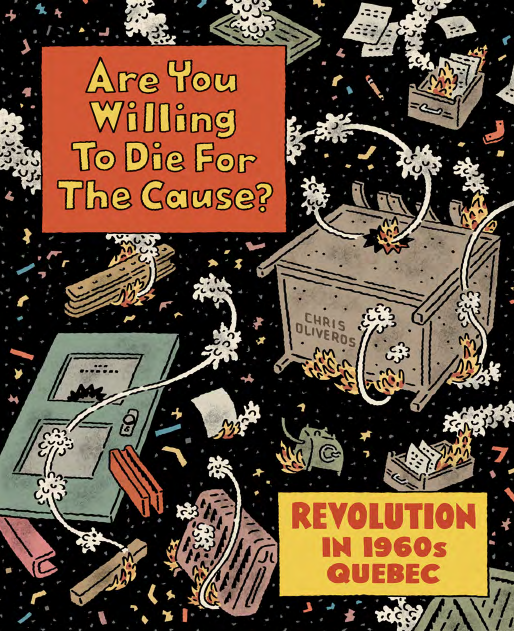

Review by Frank Plowright

The movement for French-speaking Quebec’s independence from the remainder of Canada rumbles on in the present day, but has waxed and waned for decades. The most inflammatory period, though, was during the 1960s and 1970s when various incarnations of militant organisation Le Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ – Quebec Liberation Front in English) carried out a campaign of direct violent action.

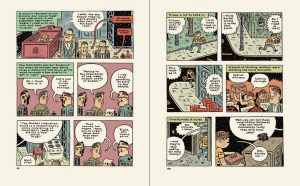

In this well researched reportage about the period, Chris Oliveros identifies contentious comments made in 1962 by Donald Gordon, President of the Canadian railway system as pivotal in sparking the movement. He saw no reason to promote French-Canadians above what he perceived as their talent level. Using the fictional artifice of recently discovered interviews recorded with the relevant people, Oliveros supplies the historical continuity. In the early days primary FLQ organiser Georges Schoeters resents the patronising attitude of the English speaking Canadian establishment to his province, and much of what angers him will be familiar to many in Scotland. Schoeters and two like-minded colleagues create a manifesto for an independent Quebec, and celebrate by attacking Montreal’s barracks with a single Molotov Cocktail apiece.

It appears Oliveros has little sympathy for the FLQ’s methods in any incarnation. Revolutionaries are portrayed as idealistic at best, and deluded at worst, reduced to resolutely ordinary and unheroic, and sometimes comedic in his precise cartooning. Were it not for the tragedy of people eventually dying due to amateur bumbling, it might seem the way events are portrayed is slapstick. Set against that are the copious end of book notes supplying additional information and context for depictions and the words placed in the dialogue balloons, with incompetence, delusion and plain bad luck decisive. Without those notes the comic section suffers from a lack of subtlety.

This could have been countered by including more examples of the attitudes and practices that prompted the FLQ. After the initial comments from Gordon grievances are less specific, such as poor treatment of factory workers. However as far as biographical information and the functioning of the FLQ’s assorted incarnations go Oliveros supplies detail and explanations in a communicative manner retaining the interest.

This is the first volume of a proposed pair with the conclusion featuring the altogether more vicious and relentless version of the FLQ.