Review by Frank Plowright

The acclaim for An Anthology of Graphic Fiction’s first volume in 2006 presented editor Ivan Brunetti with a weighty decision when a second volume was suggested. Thankfully he prioritised the quality, meaning we’re predominently treated to more work by many of the same creators rather than considering anyone represented in the first volume to be duplicated. Once again, the work spans just under a century from Winsor McCay’s 1913 Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend, a guiding principle being that quality, honesty and individuality are timeless. It enables the energetic rushed fever dreams of the rediscovered Fletcher Hanks to feature validly in the same publication as the time consuming precision of Chris Ware.

Brunetti’s in places pretentious introduction may be a joke that doesn’t transmit, but once again, his sequencing is something to be marvelled at, each strip leading into the next smoothly and thematically. As previously, he greatly admires toying with form, applicable to many contributors, but beautifully achieved on the Daniel Clowes cover, and the feeling is that the greater the density of small panels, the more Brunetti is inclined to like a strip. What then are the differences between this and the first volume? This selection features considerably more colour, and fewer excerpts from longer works, although that’s how we experience Charles Burns, Clowes, Gary Panter and Seth, and there’s immense gratitude for a traditional content listing rather than illustrations as before. The biggest difference, though is a feeling that Brunetti believed the first volume had to be representational and crowd pleasing, but a sequel can be more personal. He feels free to include less traditional work from the likes of Gilbert Hernandez.

A second volume enables the inclusion of some greats missed the first time round, with several pages devoted to the work of Harvey Kurtzman and eulogies about him, but the more recent content is likely to be polarising. Other anthologies are heavily mined for 21st century work, and what to some is personal and experimental will to others be pointless and poorly drawn. Many strips are observational rather than creative, and what stands out is work by the likes of Martin Cendreda, Megan Kelso, and John Porcellino who can draw and have something to say. It’s not that polished drawing is essential, as Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s strips work just fine, but many strips have a hollow core. What is evident is that the pre-21st century inclusions have stood the test of time and collections of those creators’ work are widely available, while more than a decade after this anthology that applies to very few of the younger creators represented. Exceptions are David Heatley, Tim Hensley, Kevin Huizenga, Anders Nilsen and Dan Zettwoch.

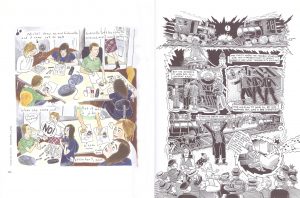

The sample spread showcases the wild variance, combining the autobiographical snapshots of Vanessa Davis with the strangely disturbing cartooning of Kim Deitch, who found his style in the early 1970s and has never diverged from it. They appear relatively early, but Vol. 2’s second half is stronger than the first, although predominantly dependent on well known names. Chester Brown’s strip on schizophrenia is a highlight, complete with explanatory notes, and there are long Robert Crumb and Clowes sections, interspersed with notable strips from Bill Griffith, Ben Katchor, Jaime Hernandez, Seth, Adrian Tomine and Carol Tyler.

While this doesn’t match its predecessor, it’s an extremely thoughtfully compiled anthology, certainly a viable contrasting of the classic and new, and at its best there are some phenomenal strips, if largely from well known names.