Review by Karl Verhoven

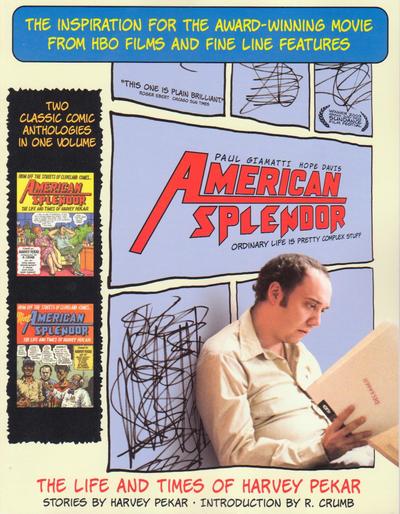

When the American Splendor movie was released in 2003, two previous collections of Harvey Pekar’s anthology were combined under a cover picturing actor Paul Giamatti portraying Pekar for the cinema screens.

The work here all dates from almost twenty years prior to the movie’s release, and there’s been no editorial tampering to the original running order of American Splendor and More American Splendor. This means the first half mixes the artistic contributions, while the second largely gathers them together in blocks. At the time Pekar had limited funds to pay artists, so not all achieve professional standards.

It’s also now noticeable that the realism Pekar strived for and demanded from his artists has already transformed some of the strips to period pieces twenty years later, as Pekar plods the street of Cleveland surrounded by the Detroit monster-size cars of the era.

So, why is this worth getting? To begin with, Pekar almost single-handedly invented autobiographical comics. There had been contributions to anthologies and Justin Green’s allegory-heavy Binky Brown, but there was no previous equivalent to the realism that Pekar made his byword. While having a passing familiarity with comics, they certainly weren’t his obsession, and he was surprised there was no equivalent of the respected autobiographical literary genre.

Pekar went further, though, in some ways pre-empting today’s personal blog. He delivers conversations, recollections, observations, and dips into his own past. There is no limit on what he covers, which can range from a pithy overheard remark to an anecdote about the joy of locating a pair of Stetson shoes in a charity shop.

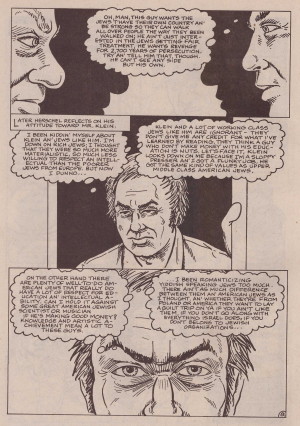

A noteworthy exemplar of Pekar’s style is ‘Free Ride’ detailing the rise and fall of his relationship with a Jewish co-worker. Pekar’s torn between disliking the man and the convenience of him providing a ride to and from work, for which he doesn’t pay. “As time goes on Herschel (Pekar’s given name) realizes that Mr. Klein isn’t interested in him. Their conversations become more and more Klein’s monologues”, and Klein is a hectoring fellow who’ll do unasked favours, but expect something in return. “It’s O.K. to screw around mit shiksas, but you dun’t vant to marry vun. You can’t trust ’em” is one of Mr Klein’s less offensive pronouncements on others.

Pekar’s contributions are almost all fine for those who enjoy his character and observations, which is, admittedly, not everyone despite the variety and insight. The artists are a different matter. Pekar was able to call on favours from an old friend, who developed into one of the most celebrated comics artists of the 20th century. Almost all of Robert Crumb’s work here is great, and he bends himself to Pekar’s material. Val Mayerik, better known as a fantasy artist and for his Marvel work is also good, and there’s a case to be made for Gerry Shamray’s method of tracing from photographs. Sean Carroll, only represented by a single strip here is up to scratch, but much of the remainder is barely functional in terms of comic storytelling. It looks basic and unappealing. Mine through it, though, and you’ll read gems such as the tale of Mr. Klein.

Beyond the material here, Pekar would never work with anyone as talented as Crumb while self-publishing, but the overall artistic standard was raised considerably by the time of 1991’s New American Splendor Anthology. The Crumb-illustrated stories alone are collected as Bob & Harv’s Comics.