Review by Colin Credle

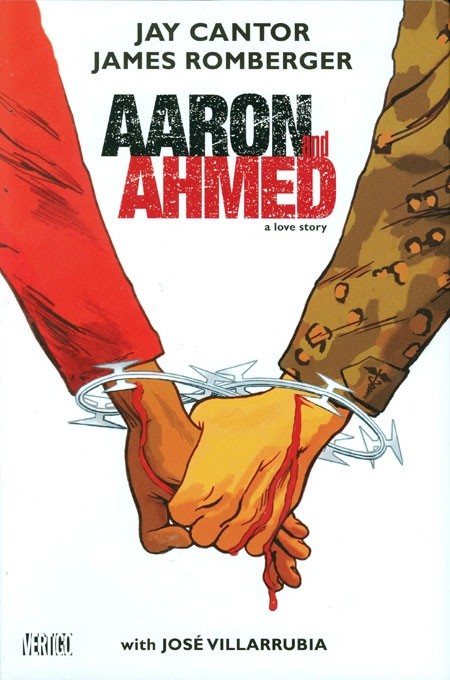

Aaron Goodman is a US military psychiatrist working with trauma patients when his wife dies in the 9/11 attacks. Feeling helpless to avenge his wife and grief stricken at his powerlessness to protect her, he joins the Global War on Terror by participating in the interrogation of Taliban prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. Amidst the prisoners, Aaron adopts a particular interest in Ahmed, deciding to single Ahmed out for a different approach in interrogation. And so the journey of Aaron and Ahmed begins.

Much like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, both are alienated, but still very much a product of their place of origin. What a strange journey it is. Although there are hints of homo eroticism, there is so much going on that their relationship remains more platonic, ideological, and based on a cameraderie of confusion, infection and propaganda than love.

Writer Jay Cantor has an interesting theory to guide us on their journey – of ideas resembling memes that can infect you like a virus, even when you don’t realise it. Initially, Dr. Goodman wants to figure out what motivates suicide bombers and fanatics. The expert at hand is a weird caricature of John Negroponte, the former US Ambassador, who supplies the meme theory. Ahmed and Dr. Goodman eventually escape Guantanamo and smuggle themselves into Afghanistan. Goodman becomes infected with the viral memes of the Assassins, an ancient order that actually existed.

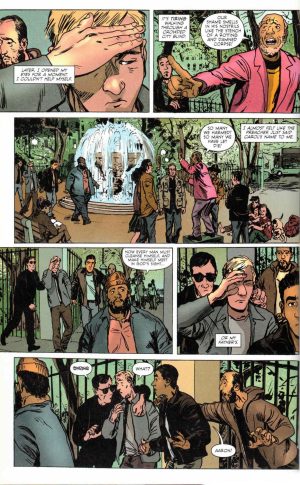

Artist James Romberger performs some adroit caricatures. The start focuses on generalizations about the war against terror, playing loose with facts and throwing them all into a blender. For instance, although it’s set at Guantanamo Bay, the torture depicted occurred at the notorious US Military prison at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Off-site interrogations committed by the US in friendly countries is also seen as taking place at Guantanamo. Some satire includes methods of questioning prisoners being inspired by comics. The psychological impact on the US soldiers doing the torturing is also off kilter in an ironic way. With this hurried and nonchalant blending of facts, it’s no longer clear where facts and history begin, where theory has a place and where the imagination of the author goes off the rails. To continue the journey with Aaron and Ahmed the reader must just go along with it.

Much disbelief needs to be suspended. The journey of Aaron and Ahmed is clearly an allegory, one that refuses to be slowed down with minor details like crossing international borders or travelling to remote locations undisturbed and unnoticed. After infiltrating the Assassins in Afghanistan, eventually, Aaron and Ahmed end up in New York City. Their progress is confusing, disjointed and lurches from strange event to stranger event, but all with a tenuous foothold on reality. It doesn’t end well.

Cantor makes his point: if you accept that adhering to an ideology is the same regardless of the ideology, there are similarities between the fanaticism of both sides of the war on terror. Are we all Manchurian Candidates? Do we accept that everyone’s moral code is relative to their subjective outlook, or is there a greater justice out there worth pursuing? The journey to understand your enemy is certainly a worthy one, usually if your intention is to win them over or defeat them. These fellow travellers end up together, confused, delirious and looking very much like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, but with less to tell us and not as entertaining.