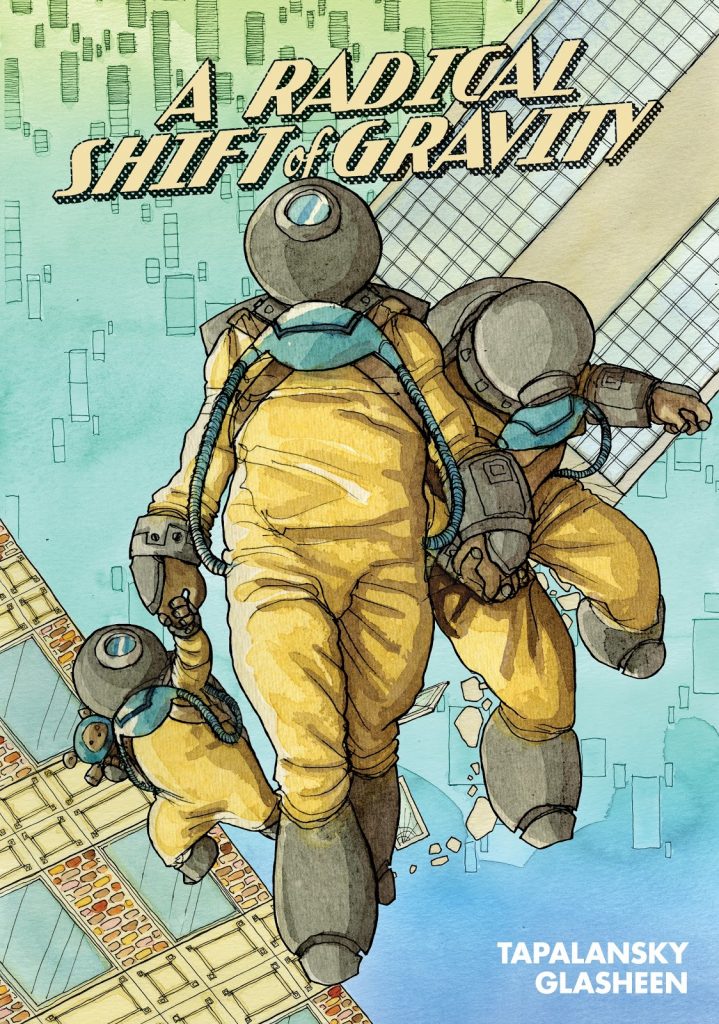

Review by Ian Keogh

A Radical Shift of Gravity uses science fiction ideas to tell an incredibly poignant family story set on an Earth that’s changing. The first modification supplies the title. Very suddenly, gravity reduces and humans are able to float. A big change in one way, it proves minor in another as it only affects humans, and after a period of change life continues as almost normal. However, scientists can’t supply any certainty, just speculation regarding the change, and over time it also becomes apparent that all is not well.

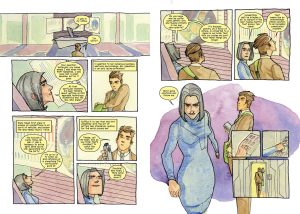

Nick Tapalansky tells his story over the lifetime of reporter Noah Hall, not chronologically, but dipping back and forth to different periods. We first meet him shortly after gravity has changed, a newspaper intern ambitious to be something more, but a succession of shunts forward in time show him as a voice in the wilderness, his relationship with his daughter fractured. Kate Glasheen’s sample art shows him meeting the story’s other prominent character, technological entrepreneur Isolde Spedmore. She’s single-minded, in her own way as ideologically driven as Noah, but focusing her interests on predicting the future. Her vast resources make her even more formidable, and we see the heartbreaking path her contacts with Noah take before meeting her properly. It exemplifies the nuanced characterisation Tapalansky applies, which may guide readers in one direction, but ultimately reinforces that with the unknown. There is no right or wrong, just differences of opinion. That applies to the strongest tie, that between Noah and his daughter Ely.

Intelligent storytelling over the different times spotlighted means readers can fill in gaps, but it takes Glasheen’s artistic poise to really cement who people are. This may surprise, because her watercolour pages with thin outlines seem too sketchy and ethereal at first, but there’s a solidity to the people, who via Glasheen let you know how they’re feeling. This is over several time periods, Glasheen ageing them well. Also notable is the subtle way she she slips in visual symbols.

For a long while Noah’s wife Sarah seems neglected, but she’s actually a pivotal character in a quiet way. This is a reflective story, meditating on what is, what can be and possible dangers, and hers is the calm voice of reason and sense. If asked, that’s probably how Noah would also view himself, and the captions formed from his columns and his interviews gradually fill in the gaps, as we follow him at different stages talking to people to fill those columns. The SF elements, though, are just the peg onto which a human story is hung. Tapalansky and Glasheen provide a thoroughly immersive experience with sophisticated storytelling that eventually builds into a complete understanding of the people concerned and their motivations.

This was created before covid swept the world, and was perhaps always conceived as an ecological allegory, yet it’s difficult not to draw completely unintended comparisons with the real world in 2022, society polarised about what the truth may be, and authority uncertain. Readers will have lumps in the throat and tears in their eyes by the end of a terribly moving story with humanity at its heart.