Review by Karl Verhoven

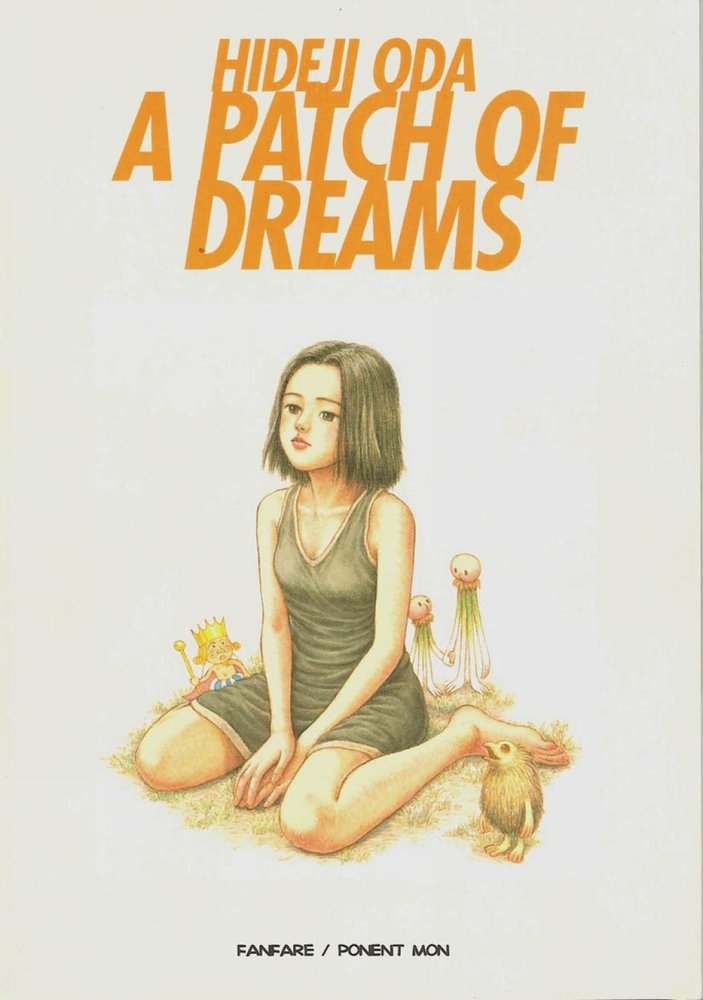

Renei Hayashi is troubled by the return of dreams continuing night after night, almost as if a TV serial. In these dreams she’s in a fantasy world where her dead step-brother is still alive, although referring to himself by different name, and very keen that Renei remain. Strange, possibly symbolic characters appear, including God, and what she experiences may also be symbolic. It’s certainly open to interpretation. At 22 there’s been a fair amount of tragedy in Renei’s life, and that of her friends, as others she’s known are also dead, and she has a constant feeling of being watched, making her life one of anxiety even before she begins seeing the people from her dreams when awake.

By introducing Renei in the opening pages, then immediately retreating to her dreamworld for an extended passage of mystery and strangeness, Hideji Oda throws readers in at the deep end. Renei’s dream persona is constantly questioning, and given the opportunity, she’s not shy when confronting God. “Why are people so complicated, so selfish…? What’s the meaning of life? There’s sorrow, misery, people hurt and kill one another! Why did you make people like that?” Disappointingly, neither God nor Oda can provide a satisfactory answer. Ultimately Oda’s not in the business of providing answers at all. There’s a certainty to his peeling back a very disturbed young woman, but tidy explanations are few. At one point during an art class, surreality is compared to a form of hyperrealty and that’s about the best we get, that some have a heightened sense of what is, and Renei is among them.

Oda’s art is problematic for a tendency to draw his cast looking far younger than they’re intended to be. The adult Renei appears pre-pubescent, and the 40 year old lecturer she sleeps with seems in his early teens. It could be a deliberate visual reference to the way people see themselves as younger when internalising trauma, a theme of the story, just as his way of drawing slightly indistinct people could be interpreted as blurring the margins between dreams and reality.

It’s not just the art that’s unsettling. For all her questions Renai is extraordinarily passive, letting herself be used and abused by others who exploit her confusion. She’s retreated inward in response to tragedies, and is now manipulated by the resulting ghosts. The only friend who offers practical advice is the one she shuns in preference to the ghosts of those who haunt her. For all that we can sympathise with Renei, there’s too much disconnection, with Oda asking us to accept a great deal without any real explanation for it. The bleeding of realities may be real, or it may be a dialogue Renei generates, and a possible reset button introduced right at the end adds to the confusion rather than dispelling it. It cements A Patch of Dreams as intriguing, but unsatisfying.