Review by Frank Plowright

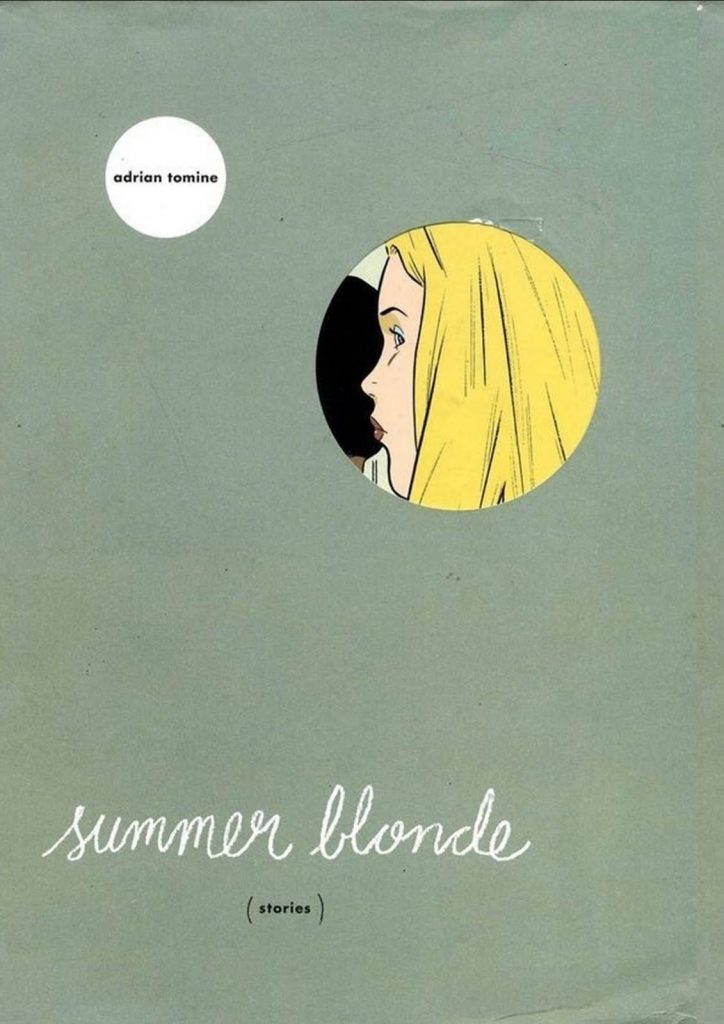

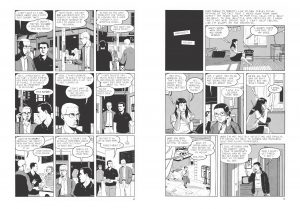

Adrian Tomine’s speciality is character dissection, introducing someone then pulling them to pieces via observation, and the four stories comprising Summer Blonde deal with emotional distance via people unable to express themselves. Martin’s lonely teenage years have become the recipe for literary success, but he’s no better at dealing with reality as he ages. Neil skulks in his room addicted to pornography with no idea how to relate to people. Hillary can do that over the phone, but in person she’s tongue-tied and intimidated by a manipulative mother, working out self-esteem issues in spurts via hurtful pranks. Scotty is fairly well living the life Martin writes about, the torture of high school.

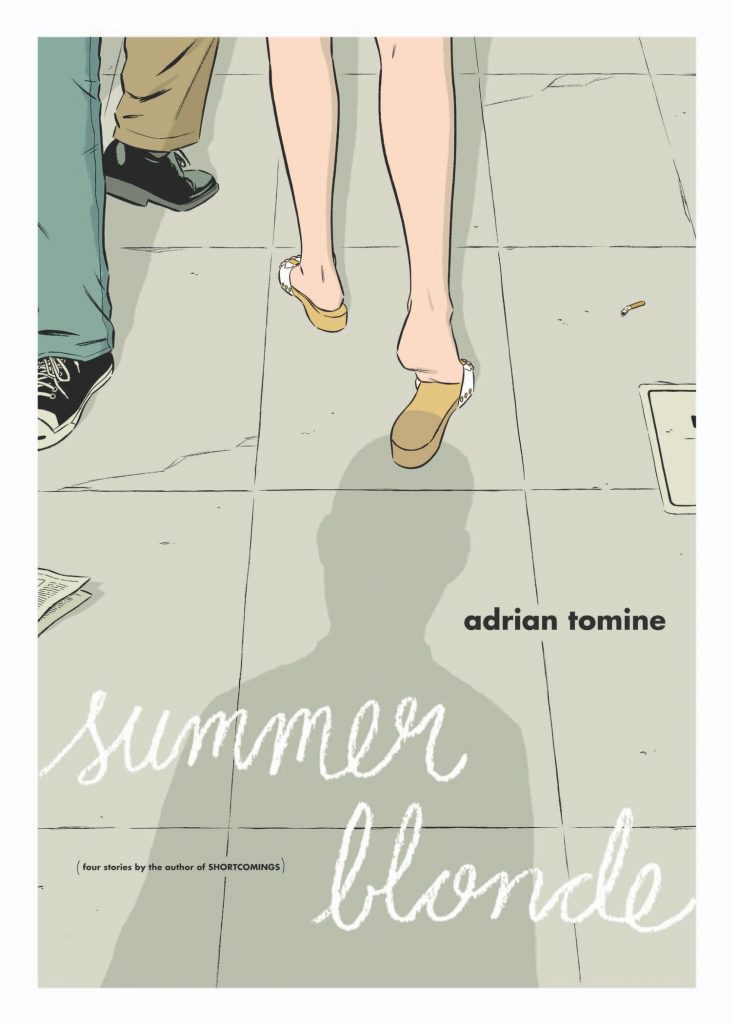

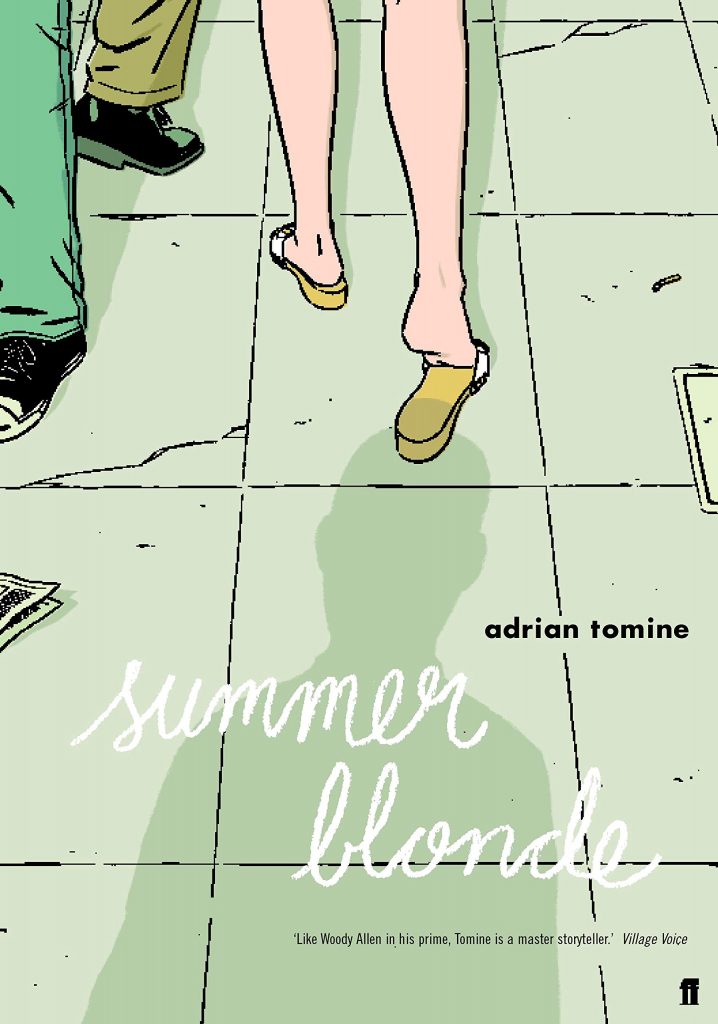

As of writing, Summer Blonde has seen four additional printings since its initial 2003 publication, which makes it a perennial success. It shows Tomine very much under the influence of Daniel Clowes, thematically, narratively and artistically, but that’s no bad thing as everything by Clowes is well drawn and he’s an expert at sucking an audience into his stories via the people.

Summer Blonde is an almost painfully self-aware selection, each story possessing a judgemental presence to reflect the self-pitying lead, and while not all feature self-inflicted and repeated wounds only one suggests any form of learning process. Additionally, the four lead characters may be different ages and genders, but via a slight difference here and there they could be the progression of a single person through life. Collectively they’re perennially disappointed despite low expectations, can’t engage and three of the four contribute greatly to their less than ideal circumstances. Here the sequence becomes important, with Scotty, the youngest of them placed last. It’s as if Tomine is suggesting that life can be different, although both we and Scotty know his joy will be brief and temporary.

Tomine is an even better artist than Clowes, his panels incredibly tight and precise catching people in a moment as if photographed, yet his art is as emotionally distanced as his characters, rarely expressing the intensity of their dialogue. Still, everything is beautifully drawn, and if the emotional content’s not there, Tomine ensures the detail of their surroundings rounds out the people.

Despite the attractive art, Tomine’s nuanced work is never going to be universal. Anyone who’s long forgotten their own younger awkwardness and frustrations will have no time for an exploration of dysfunctional people. Yet those who recognise parts of themselves are likely to find Tomine’s observations compelling.

Pages from Hillary’s story are excerpted and featured in the first Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons & True Stories.