Review by Woodrow Phoenix

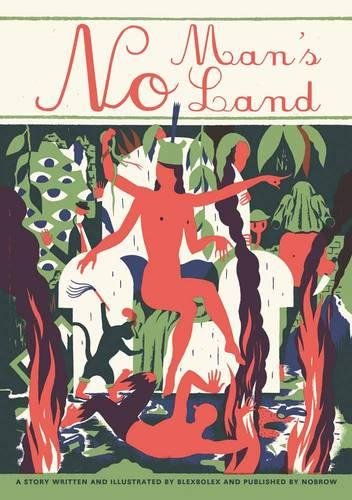

No Man’s Land is an unusual book in many ways. Its creator Blexbolex is an artist who is fascinated with the techniques of printmaking. He constructs his books as if reproducing screen prints in series, by sticking to a reduced palette of three spot colours which he overprints or holds to create complex compositions of shape and colour. Each page is one complete image. The text under each image is treated like another graphic element; blocks of capital letters that are very slightly uneven because they appear to have been made using a vintage 1950s John Bull Printing Set. Each letter has to be individually placed side by side in a wooden holder, the resulting groups of words pressed into an ink pad and then stamped onto the paper. It was basically a miniature letterpress for children. Using this naive tool (via a typeface) for the hard-boiled language of this detective existential noir crossed with some dystopian science fiction adds a layer of disorientation to his pages.

And then there’s the story itself. It begins directly where Dogcrime, which few of No Man’s Land’s readers are likely to have seen, ends: with the suicide of its protagonist. That book’s very final noir-style ending here becomes the start of a 140-page exploration of what happens in the synapses of a dying brain whirling through a barrage of increasingly strange scenarios, trying to stave off the inevitable. The first page sets up the story, showing the hero smashing a window in a burning building. The words say he’s dead: “The wounds resulting from my gunfire provoked an almost instantaneous death. At least I didn’t suffer.” But the image says something quite different, and the next sentence glides over this inconvenient beginning and carries on with the action: “The fire from the guild building has now reached the upper floors. I’ve gotta get outta here, and fast.”

Where can any story go from here? This is a detective story, so there’s only one way it can go. The crime has to be solved. The detective makes his way back to his office, where he is instantly kidnapped: “Everything looks intact, unchanged, and therefore incredibly bogus … by the time the trick is revealed, it’s too late.” From there it’s one bizarre encounter after another as he stumbles through a collapsing, militarised city on fire. The mordant narration mixes hardboiled 1940s detective novel with trippy 1970s new wave Ballardian science fiction. Blexbolex’s method of constructing beautiful images from vintage archetypes and symbols reduced to coloured silhouettes makes everything feel familiar and yet uncanny. He stretches, distorts and manipulates his shapes with colour mixes that unsettle the eye. They all work brilliantly in sequence as the action builds, halts and builds again to its conclusion. No Man’s Land is a trove of storytelling, imagery and design. The densely-woven tale takes some unpicking, but the re-reading is a pleasure with so much detail to comb through on repeated readings.

Blexbolex has made several books for readers of all ages, but like its prequel Dogcrime, this is emphatically NOT a book for children as it features violent and disturbing imagery throughout. It has not been reprinted since its initial publication in English, so although copies are not too hard to find they are very expensive. The original French edition Hors-Zone is still available and easily acquired online, so if you want to read this book, or settle for just enjoying the remarkably well-designed images, that will be your best option.