Review by Karl Verhoven

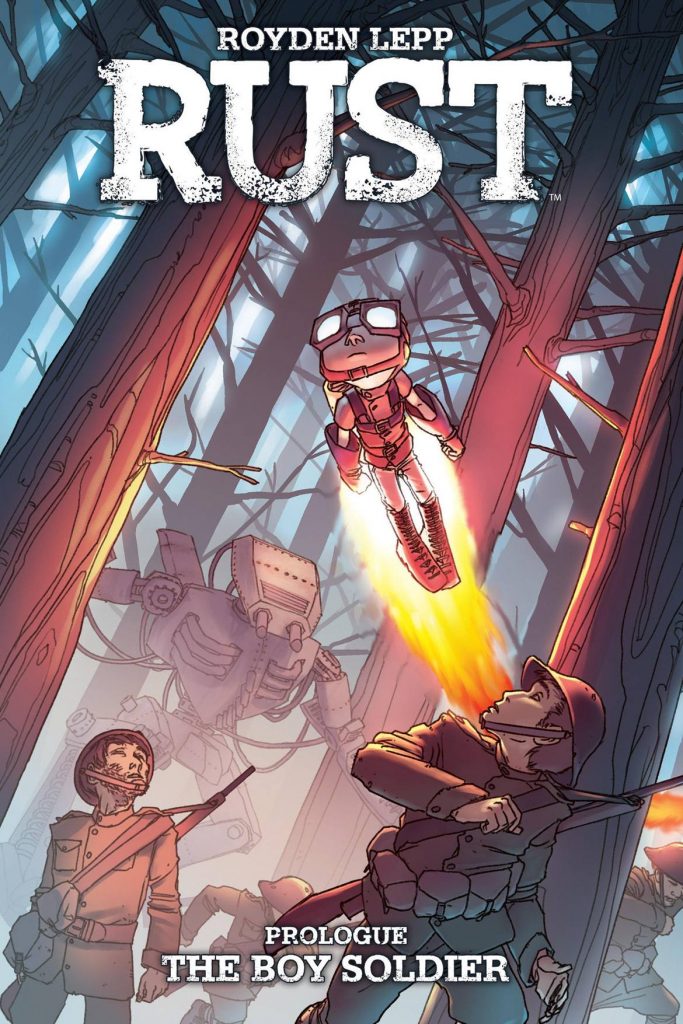

This is a prologue to the Rust series, and probably best experienced once Rust has been read, as the mood is very different from the primary story and it also clarifies significant elements kept under wraps for a while. In that, a young boy with a jet pack arrives on a remote farm, proves a hard worker, and is rapidly integrated into the farming family. This is more action based and moves at a faster pace.

The Boy Soldier combines a considerable amount of new material with the stories of Jet’s past, which feature as prologues or epilogues in the primary series. These begin with a war that occurred 48 years previously, what appear to be mid-20th century soldiers fighting a clunky looking mechanical terror, yet one still capable of scything through them. The new pages, over half the book, restore a narrative weight to the reprinted sections, which would otherwise lack impact when stripped away from the present day story that follows in Visitor in the Field.

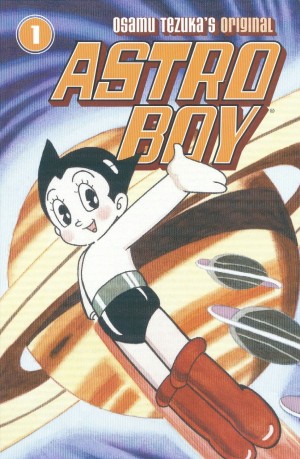

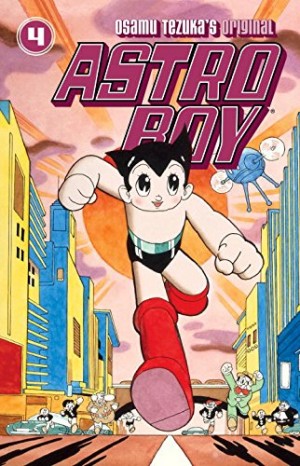

Jet is a robot constructed to resemble a young boy, with sentience well beyond the primitive, programmed killing machines he fights against, and these sequences draw far closer ties to the inspiration of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy than before. What separates them is the darkness of this story. Royden Lepp shows the horror of war without any quips or humour to distract from it, in what’s also a narrative of progressive realisation. Being more intelligent than other robots enables Jet to question the validity of what he’s doing, and the conclusions he arrives at set the course for the events of 48 years in the future. So do his actions right at the start, when Lepp shows an incident referenced in the main series. “What happened?” Jet is asked. “I don’t know. I was trying to help someone. It was an accident”, he responds in a moment of horrifying self-awareness.

Lepp’s sepia toned art effectively evokes the past, and he supplies an exceptionally sympathetic personality to a robot whose eyes we never see. As with the main series, as much as possible is presented visually, and when dialogue is used, it’s clipped and to the point. While a different type of story, it shares a prevailing melancholy with the main series, and exploits that well. Anyone who’s enjoyed the remainder is likely to enjoy this also, even if they’ve read almost half the content, as Lepp adds to and recontextualises those pages.