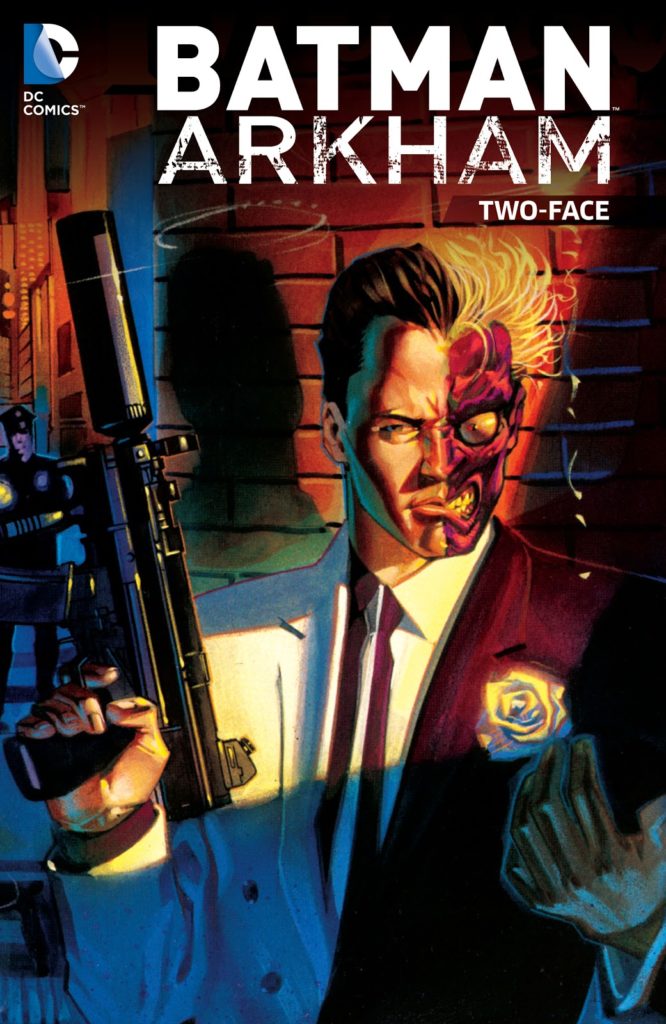

Review by Ian Keogh

Two-Face’s criminal career extends back to 1941 when Gotham’s handsome District Attorney Harvey Kent was hideously scarred by a criminal throwing acid in his face. The resulting scars were more than physical, and Kent became Two-Face, deciding his every action via the toss of a coin, one side scarred as he is. It’s been fleshed out, and Kent’s name changed to Dent, but that origin has remained essentially the same since Bill Finger and Bob Kane delivered it. The surprise is that although Kane’s art is crude and Finger’s writing tips into melodrama, their three part presentation of Two-Face still reads well. It draws on tragic horror cinema, and a scene where Dent attempts to reconcile with his fiancé over a candlelit dinner remains very powerful, while the conclusion is also well thought out.

Two-Face was discarded for being too hideous when the 1960s Batman TV show selected obscure villains, but he does appear in a 1968 teaming of Batman and Superman, where Batman declares him the foe he most fears due to his unpredictability. It’s otherwise of its time from Jim Shooter and Curt Swan. It’s the 1970 revival by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams that kickstarted Two-Face’s career, here presented in a recoloured version, but the Adams art still sumptuous. Subsequent 1980s Gerry Conway and Doug Moench stories have subplots never completed in this collection that nonetheless intrigue, which is a sign of writers doing their job well, with Moench right up to date in 1986 with a plot about computer hacking. However, while they’re all good storytellers, artists Don Newton, Gene Colan and Tom Mandrake’s versions of Two-Face are all ordinary, although Colan supplies a true grotesque for one splash page.

J. M. DeMatteis and Scott McDaniel contribute the longest story, originally released to tie in with Tommy Lee Jones playing Two-Face in a Batman movie, yet the quality transcends the purpose. DeMatteis posits that Dent was a fragmented individual long before he became physically scarred, and McDaniel accompanies this by presenting an enclosed Two-Face consistently in close-up, the visual symbolism indicating the narrative study. McDaniel also serves up cinematic posing and hyper-exaggerated action, while DeMatteis asks at what point do the sins of the past excuse the sins of the present. It’s powerful and uncomfortable reading.

A couple of fantastic art jobs follow, both accompanied by a good script. We’re more used to Sholly Fisch excelling on younger age material, but his prompting a crisis of conscience is a neat plot gorgeously drawn by Douglas Wheatley. Did David Hine name a disfigured character Holman Hunt because there’s something of the decorative Pre-Raphaelite style about Andy Clarke’s art? It’s a strange name to pick otherwise, but provides a compelling story of blackmail with a couple of nice endings. There’s an illustrative quality to Guillem March’s pages closing the collection, but Pater J. Tomasi’s plot ties in too closely to 2013’s Batman’s events, resulting in all sorts of irrelevant people interrupting Two-Face’s mad revenge plot.

It’s an unusual collection where the 1940s material has a resonance beyond the historical, but here it sets the right tone from the start for a decent collection of Two-Face stories.