Review by Karl Verhoven

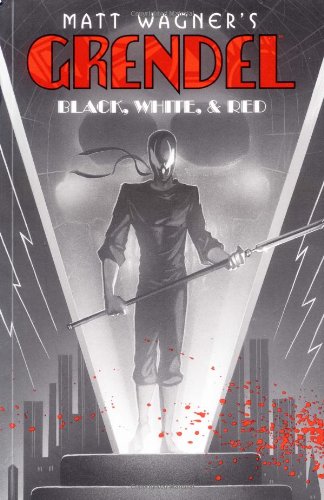

By 1998 Matt Wagner had long been content to bequeath Grendel to assorted other creators, presumably rejoicing and groaning along with us at the results, but always happy with the individuality. Grendel’s one incarnation remaining resolutely his was the original, Hunter Rose, the admired celebrity author a mask for the deadly underworld kingpin, both routes away from boredom for the exceptionally talented Rose. In Black, White & Red, Wagner returned to his creation a dozen years after detailing the circumstances of his death in Devil by the Deed, but restoring him to his prime in a series of twenty short stories, each drawn by a different artist.

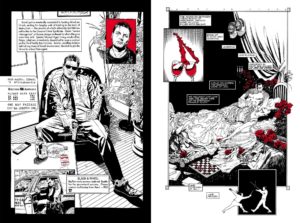

As he always did for his Grendel collaborators, Wagner selected artists with an individual vision, whether their style was figurative, cartooning or more abstract. Some he’d previously let loose on other Grendel incarnations, others were relative newcomers he gave a break, but they’re all distinct. The twisted manic energy of the Pander Brothers contrasts the calm precision of Paul Chadwick. Teddy Kristiansen’s brittle angularity opposes John Paul Leon’s imitation of still photography. There are Picasso-esque touches to Stan Shaw’s pages and an illustrative density to those of Guy Davis. It’s surely safe to say that few people other than Wagner are going to like the look of every strip included, but the scripts are thoughtfully tailored to the strengths of the collaborators, their forms as varied as the art, and their totality forming a patchwork glimpse into Rose. The sample art contrasts Tim Bradstreet’s illustrative portraiture on a journalistic trail and David Mack’s fine art designs accompanying a fragmented and poetic musing on love lost. An especially clever piece loaded with symbolism is the collaboration with Chadwick, although the power is dependent on having read Devil by the Deed. The closing lines of “I never imagined growing up. Or old. Only solitary. And serene.” possess an exceptionally vivid echo given what we know.

In some he barely appears, but each story offers insight into Grendel’s personality or working practices, some possessing greater depth than others as Wagner is working with the artist’s limitations as well as their strengths. Shaw, for instance, fails to bring the most out of Rose’s first editor’s rise and fall reduced to a smart chapter by chapter novel synopsis. Being present as Wagner dances around so many aspects of Grendel’s life using so many voices alongside so many different contributors is like watching a world class conductor manipulating the orchestration. Along the way he creates bit parts, the witness, the firebug, the ordinary man, often memorable, while Stacy and Argent are often seen. The easiest comic touchstone to apply is that of Will Eisner and Jules Feiffer’s Spirit newspaper strip in the late 1940s where not everything shone, but most did, and the sheer inventiveness of the average strip is joyful.

Dark Horse were no mugs, and three years later Wagner had conceived enough further glimpses into Hunter Rose’s world to offer Grendel: Red, White & Black. Both are now also found in the first Grendel Omnibus.