Review by Ian Keogh

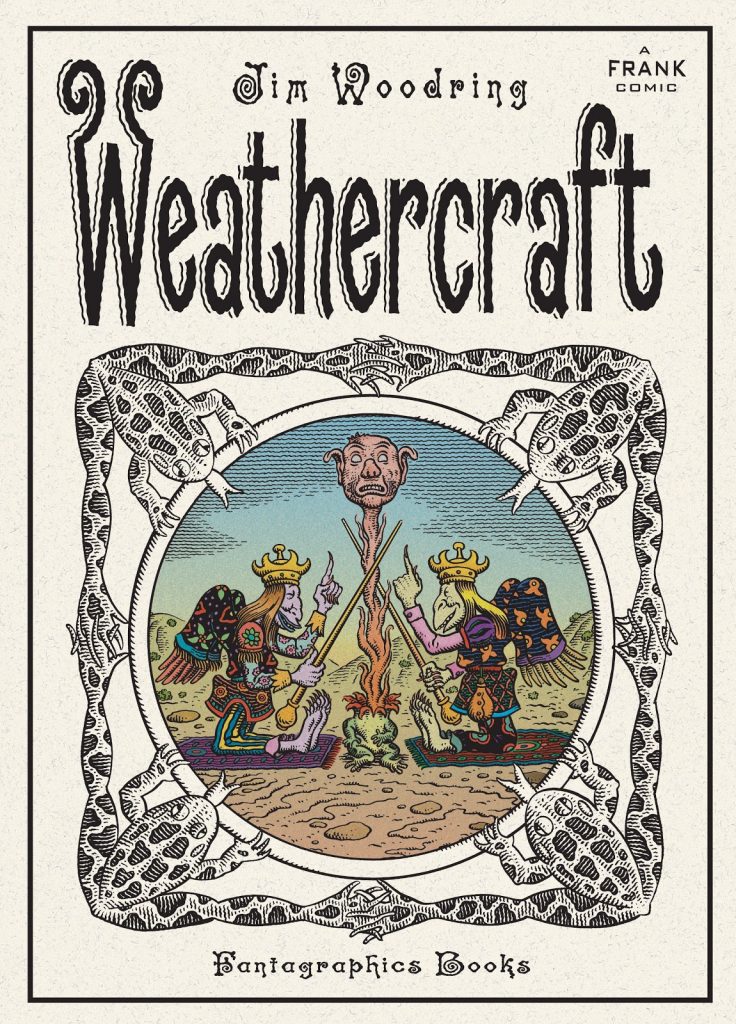

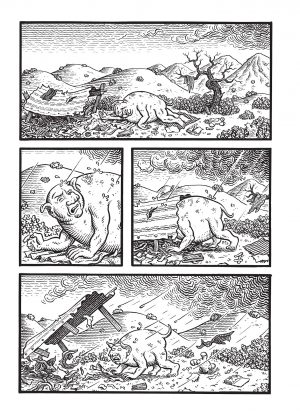

Throughout Jim Woodring’s Frank stories, Frank, and everyone else is plagued by the Manhog. He’s previously been the irredeemable villain, sneaky and vindictive, but finds the tables turned when he wanders into the wrong cave attempting to shelter from a hailstorm. It’s payback time for everything the predatory brute has inflicted on others, as he stumbles from one horrendous situation to the next. Anyone picking up Weathercraft with no knowledge of Woodring’s previous work, and it’s entirely possible to enjoy it this way, may even feel sorry for the tortures the Manhog endures.

Woodring ploughs a very narrow furrow, but exceptionally well, presenting the phantasmagorical scuttling and cavorting in front of your eyes as if glimpsing through a veil into another world. He’s an exceptional artist and designer, refined penmanship capable of creating the most intricately composed creatures and plants, squirmy horrors that mutate and transform, often with no logic other than a possibly imagined symbolism. Transformation is key to Weathercraft, though.

All earlier work by Woodring had previously been serialised, but Weathercraft is his first project in a long career conceived as a standalone graphic novel. Perhaps that why the central narrative is far less random. Instinct has always propelled the Manhog, whereas his primary victim Frank acts with far more intent, but in Weathercraft there’s a definite pattern of cause and effect, even if the means remain unclear. Events are prompted leading to a creature crawling down the Manhog’s throat. It’s only removed with a pincer like grip on something internal that’s also expelled, and with it the Manhog loses something but gains far more, now able to see and appreciate beauty in the world. He experiences life as it’s lived by others, Woodring generating cameos for his stock characters, and is given cause to contemplate the way he’s been. This shouldn’t suggest that we’re overburdened with plot. Woodring’s speciality is the serene passage through hallucinogenic environments where the wonder rests in the imaginative creations populating the panels, any protagonist often just a guide through them, and that pattern is followed.

It’s fair to say Woodring’s unique form of visual imagination is an acquired taste that will never have universal appeal, but anyone wanting to explore something different should sample Woodring’s work, and this is as accessible as it gets.