Review by Frank Plowright

When José and his wife Silvia go to empty his family’s holiday home signs of decay and neglect are apparent after it’s been empty for a year, but the memories of occasions there remain fresh. These are different for each of the now dead father’s children. Writer José remembers the constant work needing doing as akin to arriving at a slave labour camp, while the more practical Vicente enjoyed the summers spent helping out, and Carla is too young to remember holidays before the house was built.

Reflective, gentle introspective and above all humane, Paco Roca explores the tensions that exist within all families, both between siblings and between children and their parents. We see the present generation as adults, now with their own responsibilities, reflecting on the past, yet still not really understanding their father and his values. It’s a clever aspect of Roca’s writing that we understand him better than his children by combining the views and recollections each has of him. He might not have been an expert craftsman, but there was a pragmatism about his work, and what was mistaken for isolation was actually a desire to gather the family, except no-one shared his vision. Eventually we can conclude the house his family are now considering selling, in effect was their father. As his children reflect on his personality, they’re unconsciously creating the unpleasant memories their own children will one day complain about, Vicente’s teenage son hating the idea of crapping in the wild because his father’s fixing the leaky cistern.

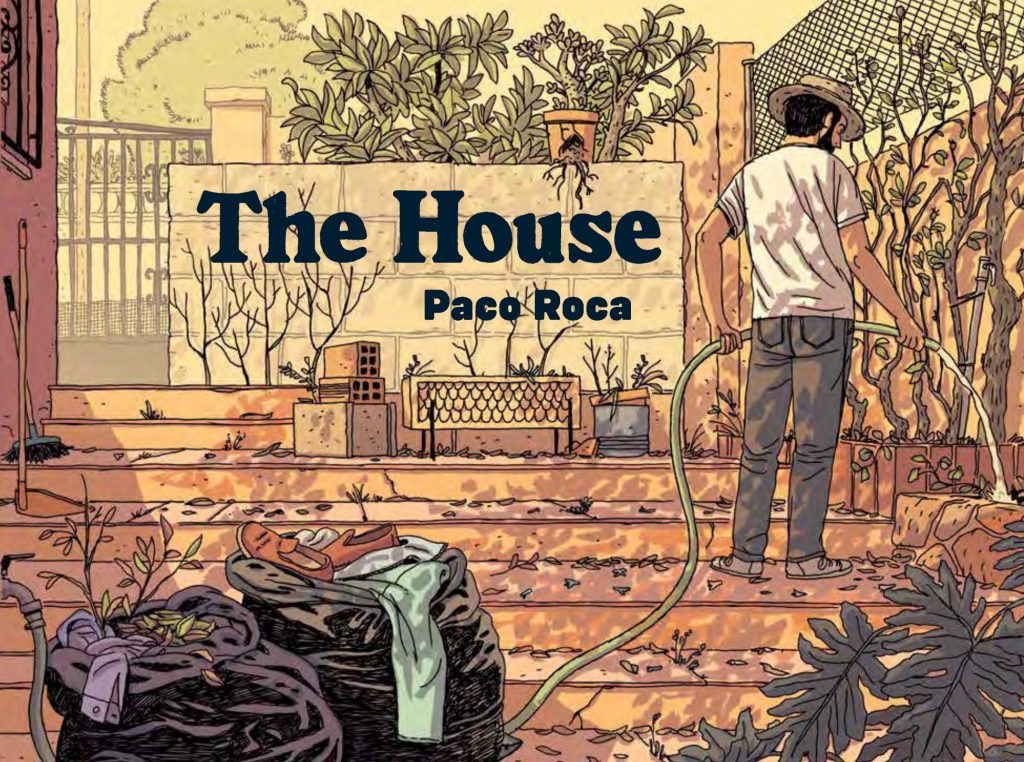

Roca’s art is impeccable, everything simply drawn, the viewpoint rarely straying from the middle distance, placing readers as observers as the family go about their business. For all the simplicity, though, the emotional connection is there in the way Roca poses his cast, and with the slight differences and adjustments in the house, past and present. That aspect alone indicates the care Roca takes.

The House is dedicated to Roca’s father, and ends with a photograph of the two of them sitting together on a bench that could be outside a holiday home. It can’t be coincidental that Roca draws José in a shirt similar to the one he wears in that picture, yet there’s no description of his work as being in any way a memoir. It’s a landscape format graphic novel where the observations at first seem too ordinary, yet The House becomes something very special, an intimate immersion to be cherished and re-read.