Review by Frank Plowright

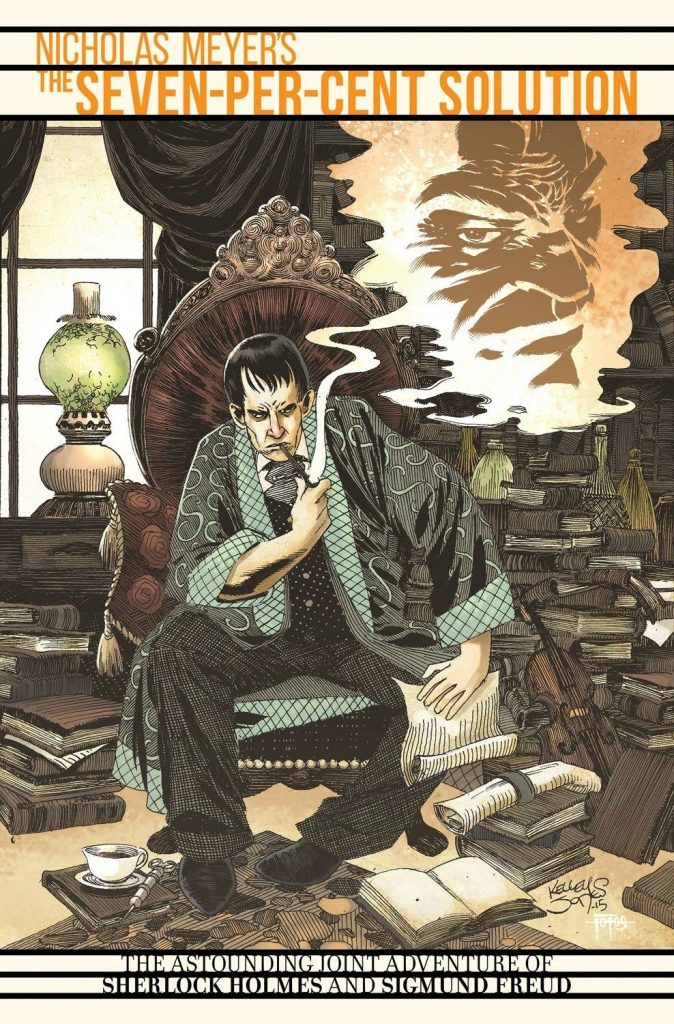

The Seven Per-Cent solution was developed by American screenwriter Nicholas Meyer to keep himself busy during a strike. He conceived the meeting of Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud as a novel, published in 1974, and two years later he wrote the screenplay for the film adaptation. In 2016 it was the turn of David Tipton and Scott Tipton, to adapt Meyer’s work.

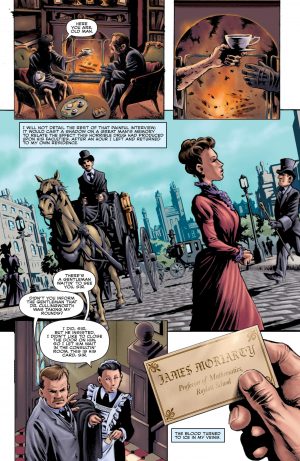

It begins with an 87 year old Dr Watson in 1939 confessing that two of the books he wrote about Holmes’ adventures are fabrications. There was no death at the Reichenbach Falls, nor a miraculous return. Instead there was the case he’s about to reveal, one that couldn’t previously be told out of respect to two parties, the then recently deceased Freud, and Holmes himself, who found the dissection of his own character distasteful. It’s certainly an iconoclastic depiction. To being with we rarely see the composed and intellectual Holmes, but a man paranoid about one Moriarty, a genius whose nefarious deeds he believes are being covered up. When Moriarty comes to call on Watson, it’s as a man claiming to be persecuted by Holmes. The conclusion Watson reaches is that Holmes’ cocaine addiction is gradually driving him mad, and his only hope lies in consulting with a psychiatrist who once endorsed cocaine, yet how will Holmes be induced to travel to Vienna, never mind unburden himself?

While well enough constructed to serve as a genuine adventure, much about The Seven Per-Cent Solution is also pastiche, exaggerating the already improbable methods Holmes uses. A dog follows a scent across a continent, Holmes used preposterous disguises, and his deductions are brilliantly impossible. If treated too disrespectfully the novelty might rapidly evaporate, but for all his eccentricities Holmes isn’t portrayed as an idiot. His deductive intellect remains intact, and while we eventually see a Holmes not seen before, it’s a largely respectful creative vision. Artist Ron Joseph skilfully depicts both attitudes, his style a halfway point between realism and caricature. His method with the many talking sequences keeps them visually interesting, and he piles in the period detail. The only times he fails to impress are with the big action set pieces, where the view needs to be from distance for maximum impact.

Via the use of cocaine addiction and intervention in some ways this is as modern a take on the great Victorian detective as Sherlock, but Meyer’s story eventually hinges on fitting everything into five chapters. In this context remaining faithful to Meyer’s novel requires considerable dumps of dialogue on the part of the Tipton brothers, and would have been better served by being extended to a sixth chapter. They bring through the need for Freud’s psychological expertise to be added to Holmes’ deductive intellect, and define Watson well, never used as a comedy figure despite this being part satire. A clever conclusion explains much about Holmes and his attitudes, and why Meyer’s book remains highly regarded. Anyone whose interest in Sherlock Holmes has been prompted by the 21st century TV series could do far worse than pick this up.