Review by Ian Keogh

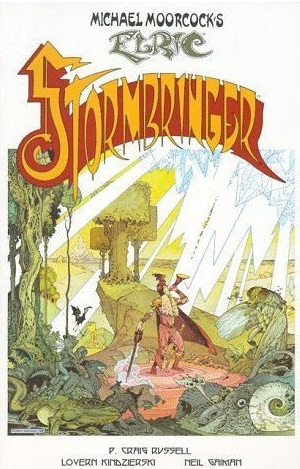

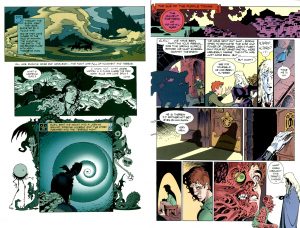

For many people P. Craig Russell has drawn the definitive Elric, The Dreaming City in 1982 setting the standard. He subsequently contributed pages to works primarily drawn by others, but Stormbringer in 1997 was his first full Elric in fifteen years. Chronologically, the story is Michael Moorcock drawing Elric to his final destiny over four novellas, yet completed in 1964, it predates most exploration of Elric’s earlier life. To differentiate him from the Elric of that earlier life, Russell now draws him as a more commonplace fantasy hero, no longer gaunt and frail, but of normal physique and with his hair flowing rather than tied back or hanging. In this incarnation he resembles nothing so much as 1990s WWE wrestler. It’s not the only difference between this and Russell’s earlier work. His style and approach had been considerably refined over fifteen years, and Russell now broke down his pages into multiple small illustrations, rarely opening up into anything occupying half a page, never mind larger. Each individual drawing is excellent, but they don’t convey Elric’s power and the expanse of his world. These panels also incorporate amounts of text that cross the line beyond being faithful to Moorcock’s original text to become excessive, and the drawing often matches the text as if an illustrated story rather than a comic.

Early in Stormbringer Elric’s partner Zarozinia is abducted. Despite vowing never to use his soul-sucking sword Stormbringer again, circumstances dictate. Elric soon figures out where Zarozinia has been taken, but not why, and becomes irritated that friends and foes are aware of prophesies about him that he’s discounted. The capricious god Arioch seems disinclined to come to Elric’s aid when petitioned, and he learns of even older gods with destructive purpose. Moorcock’s story is packed with verve and imagination, and he successfully introduces an atmosphere of doom and finality, well exploited by Russell. Stormbringer is episodic, a series of missions collecting artifacts, in which many people Elric had earlier met return for a valedictory salute.

Very much of note is the colouring. Russell had previously coloured his own work, producing a brightness distinguishing his pages from all others, but by 1997 he’d begun his almost symbiotic relationship with Lovern Kindzierski, and the bold and vivid colours are visionary. Kindzierski was an early adopter of digital technology, and time and again the richness of the colours catch the eye. Even with all the computer wizardry now available, Kindzierski’s not been surpassed.

When written, Moorcock intended Stormbringer as the final word on Elric, and he didn’t intend a happy ending as he explored the twins of chaos and fate. Prophecies about Elric have been dire and dreadful, and Moorcock sees they’re all fulfilled. It makes the final third of the graphic novel very grim reading, as this mopping up exercise lacks sentiment and is extremely thorough. There’s even the irony of a final chapter being titled ‘The Comedy is Over’, this in the bleakest and most introspective of fantasy series. There are times when Russell could have elected to let the story breathe a little, to depart from the rigidity of small panels, but only does so to incorporate blocks of text. Set against the overall beauty this will be easily overlooked by most in what’s a visual tour de force.

The long out of print 1998 graphic novel commands high prices, but with Titan reprinting all the earlier Elric adaptations alongside new versions, the patient will be rewarded. Just to avoid any confusion, the story told in the 21st century European Stormbringer is from earlier in Elric’s career.