Review by Karl Verhoven

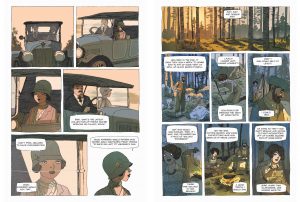

Emma G. Wildford is a poet, forthright and unconventional, even for a 1920s era slowly shrugging off the constricting Victorian mentality, her character beautifully established in an opening sequence set at her sister’s opulent home. It’s been five months since anyone heard from her fiancé Roald, following the family exploration trade by undertaking an Arctic trip for the Royal Geographic Society. His unfortunate ancestry features many explorers who’ve died at their passion, and the common feeling is that he’s now shared their fate, but Emma retains faith as further months pass. When she receives no help from others she decides to mount her own rescue mission.

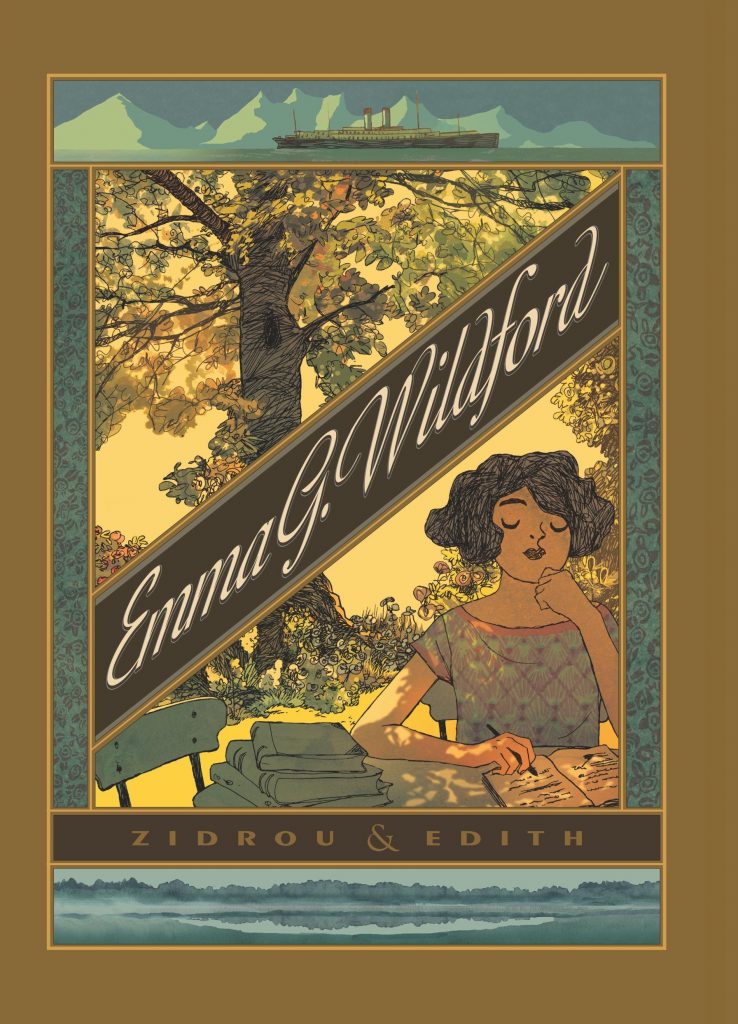

Benoit Drousie writes under the alias Zidrou, and very little of his substantial output has been translated into English, which on the basis of Emma G. Wildford is a considerable oversight. Emma’s speciality is the cutting quip or pithy comment over one or two lines, possessing insight and humour – “What can you know of it brother-in-law? Have you been pregnant before?”. Writing a maverick convincingly requires a considerable wit, and in Zidrou’s case it’s matched by a facility for poetry, and some interesting comments about nature (“The first snows always come as scouts. Then they go fetch the rest of the army”). The subtlety that Drousie brings to the dialogue and narrative captions is also evident in the plot and pacing, as he weaves a fabulous adventure about a fabulous woman. His delicacy is matched by artist Edith (Grattery) whose visual characterisation matches the verbal sparkle and brings opposite landscapes to life. There’s great beauty about both her sweltering English summer and her frozen Finnish views, the use of lighting to accentuate what nature provides exceptional, making these views to become lost in, deeper than the fog enveloping the ship on which Emma leaves Newcastle.

When a French creative team produces a quintessentially English story featuring a British cast, the enquiring mind wonders why the story wasn’t set in France during the 1920s when surely all prerequisites were present. That has no answer, but everything is so perfectly judged, does the answer matter? Hanging over Emma’s adventure is a letter. It’s almost the first object we see, and has been left by Roald to be opened if he doesn’t return from his expedition. Emma has refused to open it, her faith in his survival absolute. There’s a rule about writing plays that no prominent object should be shown if it doesn’t have a later purpose, and the letter’s purpose is revelatory and enabling, a fantastic twist permitting what most readers will surely have by then considered inevitable. However, Zidrou ensures events don’t play out as predictably, in a wonderfully judged spiritual and humane ending.

A final shout out needs to be given to Mark Bourbon-Crook, translator from the French, whose task guarantees there’s a richness to be savoured in this English language edition. A poor translation would have sabotaged it. Emma G. Wildford is a superb evocation of a bygone age, a paean to nature and a plain wonderful story. Don’t miss out.