Review by Frank Plowright

It was widely promoted that the current Batwoman persona was deliberately created to diversify DC’s characters. It might well be asked, however, that if the purpose was to introduce a high profile lesbian superheroine it’s hardly pushing the boat out if she’s also a wealthy white socialite. While Kate Kane’s gender preference drew all the original headlines, Elegy‘s quality soon ensured that issue was secondary, and it’s a graphic novel that remains a compelling read.

Despite few previous appearances (if her sappy 1950s predecessor is discounted), Batwoman was thrown into continuity as the complete article, fighting crime and known to Batman, with much of her backstory revealed here for the first time. Her odd relationship with her military father is established early. She refers to him as “Sir” or “Colonel” and notes he’s trained her and is aware of her costumed activities, if having a natural parental concern.

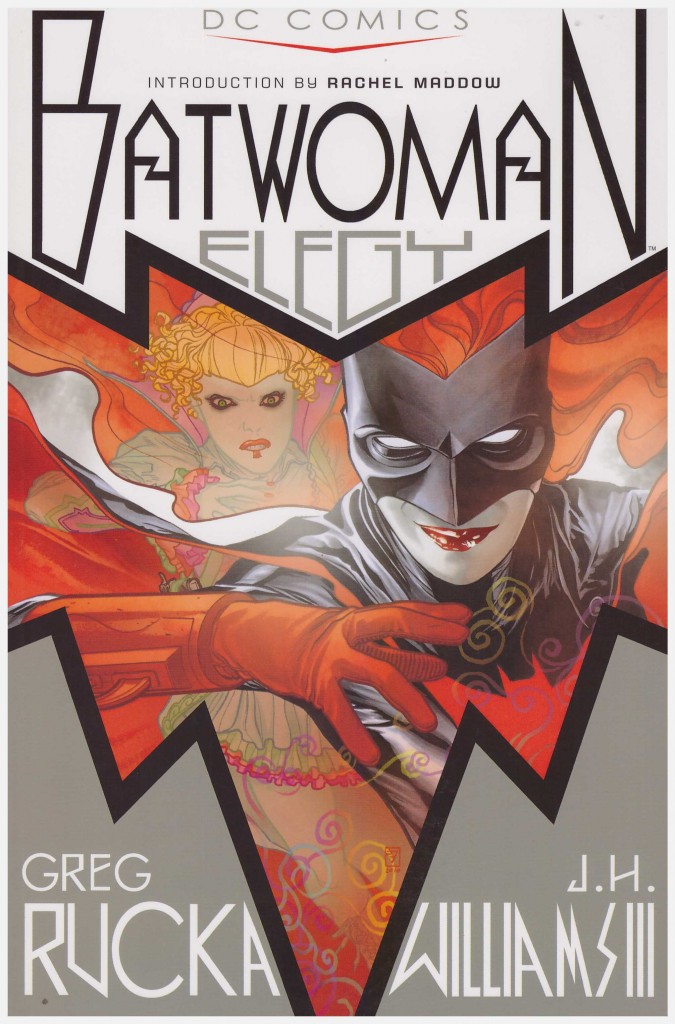

As the book opens Batwoman is on the trail of an organisation called the Religion of Crime, who’d previously almost killed her. They appear intent on completing the task, and with their leader due to visit Gotham Kate wants some questions answered. This leader is a pallid horror in 19th century dress calling herself Alice and delivering much of her dialogue in Lewis Carroll quotes. This could become arch and tiresome, but writer Greg Rucka ensures Alice retains her threat without ever descending into farce.

Midway through the book there’s quite the shocking revelation, although the observant might have made a guess, and from that point there’s a distinctly different tone when the past is spotlighted and the path from Army cadet to Batwoman is revealed. It also by necessity ramps up the role for Jacob Kane, who becomes a fascinating character. He’s completely supportive of his daughter, yet his military background has instilled an emotional detachment that’s led to mistakes being made.

The art of J.H. Williams III is a major factor in Batwoman’s success. While a more commercial project demanded he toned down his experimentation a little from Promethea, his layouts are bold and decorative, often within a bat motif. The ornate wonders abound. Early in the story there’s an almost hallucinogenic sequence featuring Corbenesque monsters, reprised to greater effect towards the end, there’s a wonderful juxtaposition of night and day over a double page spread, and there are plenty more beauties to gaze at. When sequences from Kate’s past are required Williams varies his style to distinguish this, turning in flatter art. He’s helped greatly by the colouring, with Dave Stewart thoughtful throughout, providing vivid red highlights on Batwoman’s costume standing out against the dark of her world. The manner in which Williams distinguishes Kate and Batwoman via posture and expression is very gracefully handled, with intuitive moments of strength even without the costume.

So, the art is stunning, and the first part of the story resolutely accepting of Kate’s nature without highlighting it as worthy, elements of the second section slip into exploitative imagery. As there were alternative methods of portraying the scene concerned it’s hypocritical, a case of DC (or the creators) wanting to have their cake and eat it.

This isn’t enough, however, to negate the power of Elegy overall. Rucka’s strength is character based crime stories, and Williams’ decorative interpretation of his material elevates it well beyond a standard superhero story.

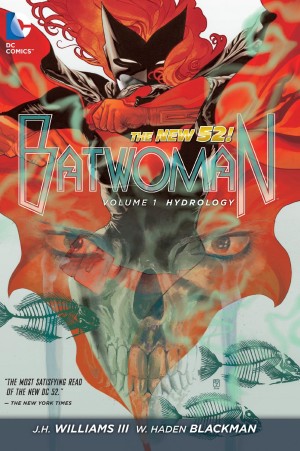

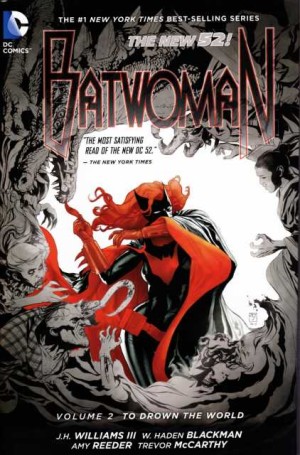

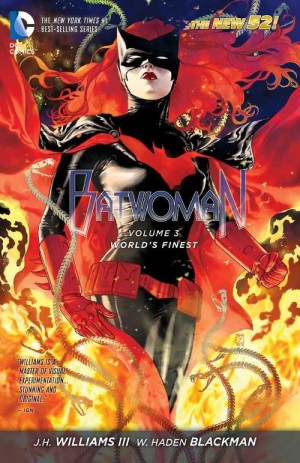

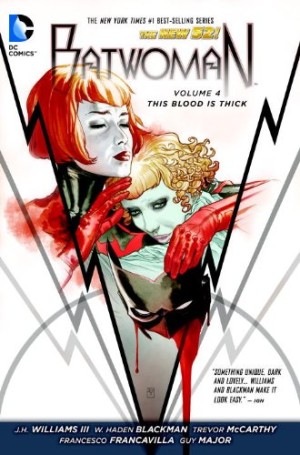

Success led to an ongoing Batwoman series with Williams III remaining on art, beginning with Hydrology, and Elegy was reissued with a new cover to coincide with the Batwoman TV show.