Review by Frank Plowright

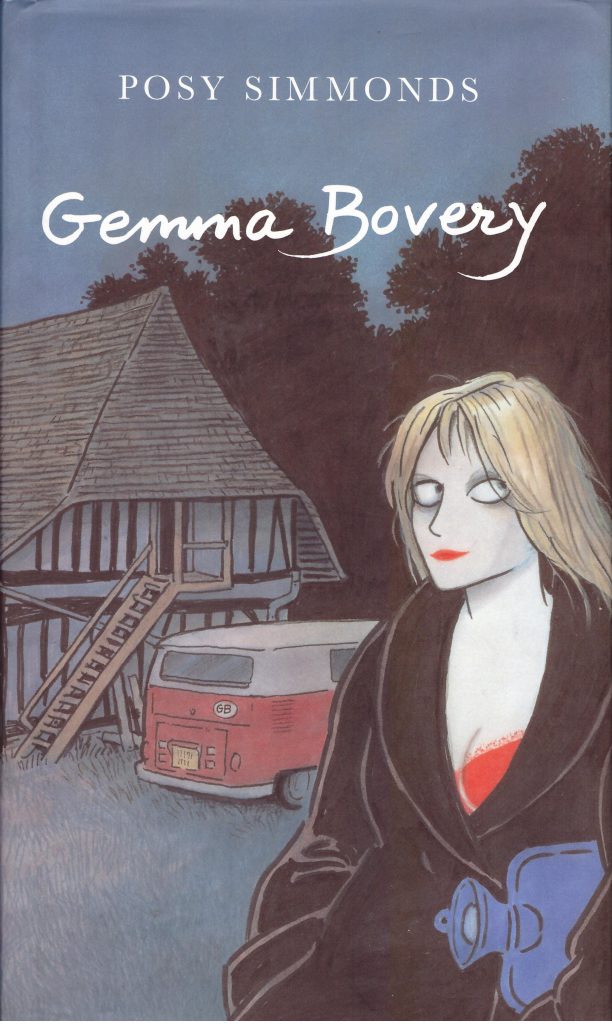

Gustave Flaubert’s début novel was the tragic tale of Madame Bovary, and Posy Simmonds adapts the broadest elements, acknowledged in her title character. Gemma Bovery is a young English woman who moves to Normandy with her furniture restoring husband, and is ill suited to the tranquillity of small town life, rapidly becoming bored and frustrated. Unhappy when she first met Charlie Bovery, she’s aware she’s made the wrong choice of husband and home. Flaubert’s story ended in tragedy, and Simmonds’ opening statement ensures we’re under no illusions Gemma Bovery follows the same path, and she underlines this throughout.

The narrative voice is that of local baker and freelance literary critic Raymond Joubert. Via his complicity and Gemma’s diaries, which he’s purloined, the past unfolds second hand, filtered through the extra layer of Joubert’s judgemental comments. He’s a man with a vested interest and his guilt about how events played out hangs heavy.

Simmonds modified her tale considerably for book publication, editing, adding and correcting, and in terms of style it’s a strange beast. Passages of text are accompanied by emotionally appropriate illustrations, with the more traditional looking comics content gradually incorporated. The combination permits Simmonds’ customary observant detail, and Gemma’s former lover Patrick, food critic, is constructed from his work and possessions. He’s introduced via her diaries with Joubert’s acerbic commentary on his nature and work. Much of the cast fit into the common British character types Simmonds satirised for years in her previous newspaper strips, and there’s a wonderful precision about both her language and her illustration, which combine to greatest effect in Judi, Charlie’s manipulative and controlling ex-wife. She can hone in on a victim and lacks any compunction about making their lives worse. Several other base characteristics receive airings in passing, not restricted to snobbery, xenophobia and self-interest, here not the exclusive province of the British middle classes. There are also some glorious small observations. Joubert notices the GB sticker on the Bovery’s car corresponds to Gemma’s initials, and he’s enraged that British moving to France never consider French people a reason.

On one level this is very familiar territory for Simmonds, microscopically spotlighting the delusional self-pity of people for whom hardship is the local supermarket lacking asparagus and persimmons. What raises it above that is the attention to character, and the clever way in which Flaubert’s novel is both followed and parodied. The financial problems that beset Madame Bovary receive a 20th century transformation and there’s a post-modern application of the idea that the cast are fighting to escape the fates of their Flaubert counterparts. Not all do.

What for Simmonds is an almost frenetic finish occurs after the leisurely escalation of tension, and there’s a joyous perception in how she subverts reader expectations with regard to the final pages. Joubert has frequently referred to his conviction that Gemma’s death is his responsibility, and the way Simmonds brings this home to roost is magnificent. But then so is almost all the remainder. Gemma Bovery is a graphic novel anyone with intelligence and a sense of humour should love, and it shouldn’t be confused with the well-meaning, but somewhat tepid later film adaptation. That just underlines how much comics have to offer as a storytelling medium.