Review by Frank Plowright

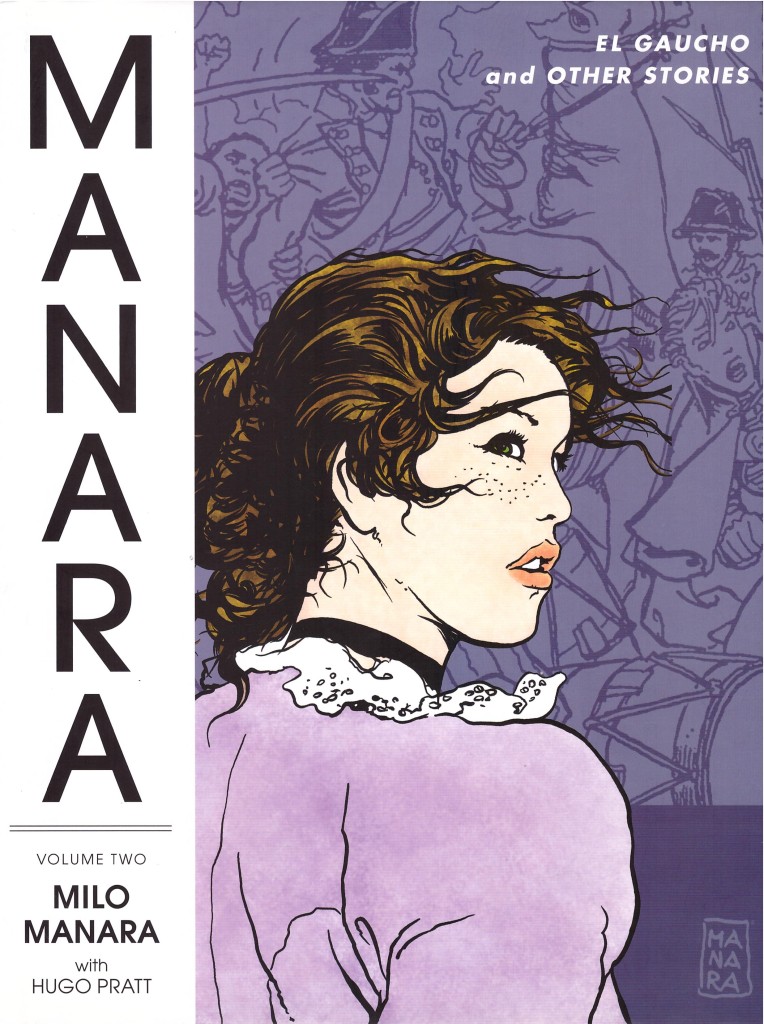

This second volume archiving Milo Manara’s career again features a collaboration with fellow giant of European comics Hugo Pratt, again on a historical drama, but the major attraction for some will be the second feature ‘Trial by Jury’, never previously seen in English.

Pratt and Manara’s collaboration on the historical drama of El Gaucho took three years to complete when originally serialised in Italy from 1991, and Kim Thompson’s new translation is far superior to that provided for NBM’s 1996 English language edition. There’s a nuance and ear for colloquialism absent from the previous version, but El Gaucho still isn’t as satisfying as volume one‘s Indian Summer. A review of the individual graphic novel provides greater detail, but the fault lies with Pratt, whose plot meanders while incorporating a multitude of extraneous detail and several cast members whose influence and purpose is minimal. Where it works, there are great sequences, and Pratt’s writing skills are evident on a couple of occasions where he provides memorable scenes seemingly without greater purpose that are actually pivotal to the story. Manara’s contribution is gorgeous, with convincing historical detail and a lively cast depicted with real character. There’s a certain similarity to Manara’s universally attractive pouting women, and that detracts from how good he is at distinguishing the male members of the cast, each provided with a different look and characteristics.

‘Trial by Jury’ is an oddity created in the mid-1970s, largely twelve page tales in which historical figures are brought to court to answer for their transgressions. Mino Milani’s scripts identify some obvious slaughterers such as Roman Emperor Nero, Latin America conqueror Hernàn Cortés and Attila the Hun, but an interesting aspect is the European view of people still revered as heroes in their homelands. Admiral Yamamoto is one, and the only colour strip places George Custer in a far from flattering light.

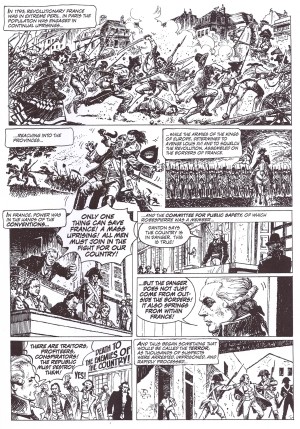

The format followed is an opening text statement accompanied by Manara’s portraits of the accused in the dock, and a further text exchange prior to the strip content. This, though, can be interrupted again for more conversational exchanges. This hybrid method is unsatisfying. Whether due to a limited page count or Manara unwilling to draw a page of talking heads to convey the longer exchanges, it interrupts the flow of what’s happening. When both sides have presented their case there’s a text summing up from prosecution and defence, and the reader is cast as judge to deliver the verdict.

It’s a clever conceit, educating via the having one’s cake and eating it method later so successfully employed by Horrible Histories. There’s enough gruesome content to keep the reader interested if Manara’s glorious rendition of battles and other historical wonders isn’t enough. A clue to Manara’s future artistic career is provided when Helen of Troy is charged for her infidelity starting the Trojan War, then hauled back into court for a second strip when new evidence emerges. This is early Manara, and while there can be no complaint about the art, it’s fascinating to see the visual elements he’d later discard. These are, often of necessity, extremely packed panels. Just look at the detail in so many panels of the sample page (French Revolution hardliner Maximilien Robespierre’s trial), and the stippling Manara applies to faces in these strips is a novelty.

This is the Manara Library, and his work throughout is first rate, if in different styles. As comics, however, the contributions of others don’t match his.