Review by Karl Verhoven

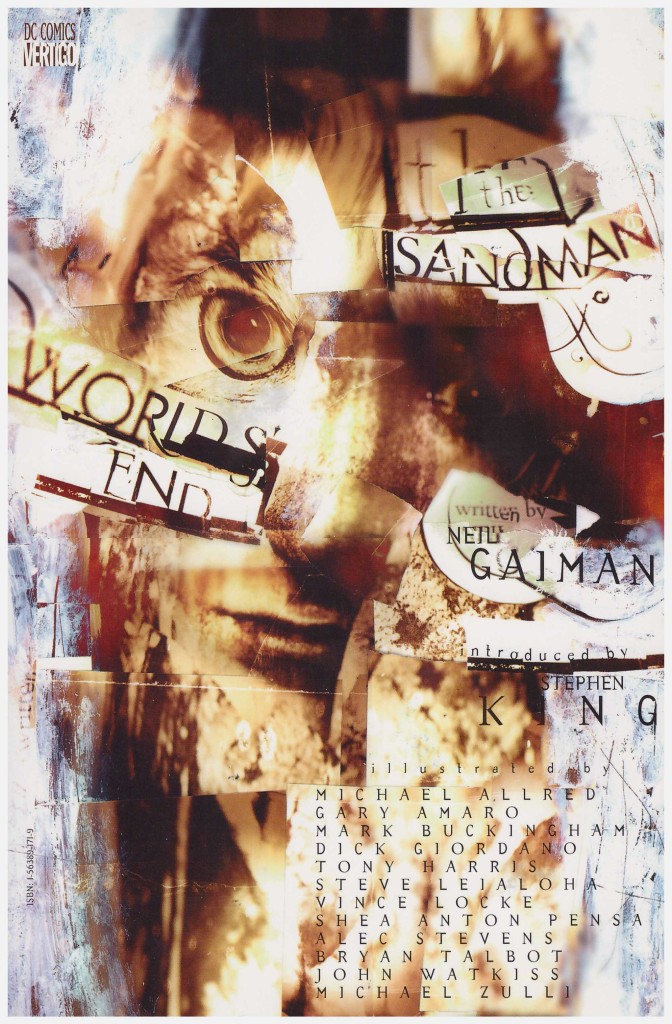

For World’s End Neil Gaiman adopts the framework of The Canterbury Tales, with the convivial company of a hostelry in which many are trapped. What human Brad had assumed to be an odd snowstorm in June, is identified by others, centaurs, faerie and the like, as a reality storm, and they’re passing the time by telling tales until it dissipates.

In the context of Sandman, much the same could be said of Gaiman, killing time before embarking on The Kindly Ones. If any confirmation were required at this stage that he’s a natural storyteller, the breadth and scope of World’s End provides it, even incorporating tales within tales. We have a cautionary fable about a scoundrel conjoining church and state, the dreams of cities, the clasp of silence, and even a re-imagining of one of DC’s wackiest old series, Prez. It’s as if Gaiman is exorcising himself by experimenting with material he’d not be able to relate in other comics. It’s almost all very engaging and satisfactory.

In his afterword Gaiman notes he constructed his stories around the strengths of the artists he was scheduled to work with, which is an interesting and adaptable approach to writing, not to mention confident given the vastly varying artistic styles. The structured formalism of Alec Stevens is employed to good effect with an updated take on Lovecraft and Poe’s paranoid mood of all not being as it should be. Stevens responds with an excellent sparsity and claustrophobic layouts reminiscent of Bernie Krigstein.

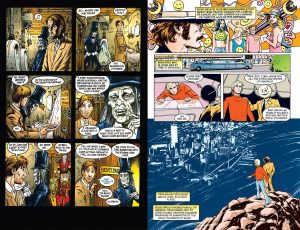

Bryan Talbot (sample art left) needs no telling what the inside of a pub looks like, and provides the character packed bridging sequences in his detailed fashion. The cast burst from the panels, rather than being awkwardly confined by them as they are in the work of John Watkiss. Talbot’s given a portentous set piece near the end, and delivers it in spectacular fashion. Michael Zulli’s on good form for the return of Hob Gadling, the man who will not die, and Michael Allred’s take on Prez is inspired (sample right).

This isn’t a perfect collection, though, as the forced pomposity and procedure of a land that ritualises funerals never quite pulls together. It lacks elegance, and Shea Anton Pensa’s art is very ordinary.

An interesting element occurs in the final chapter when a female character rants about the preceding content: “They’re all boys own stories”, and later “And I’ll tell you something else I noticed, there aren’t any women in these stories. Did anyone else notice that?” It’s awkward, as if this had been a late realisation on Gaiman’s part and he’s been overcome by a bout of political correctness. It’s a balance redressed in The Kindly Ones.

The content here has been re-mastered for volume three of Absolute Sandman, where it’s presented in an oversize format in a hardcover book and accompanying slipcase. Those re-mastered pages also appear in volume two of the bulky Sandman Omnibus, while volume three of The Annotated Sandman features Gaiman’s inspirations and references on a page by page, and sometimes panel by panel basis. There the art is in black and white.

For those on a budget whose preferred choice is the traditional paperback format, the production tinkering is relatively minimal, so the choice amounts to preference regarding the original colouring or the updated palette in post 2010 editions.