Review by Ian Keogh

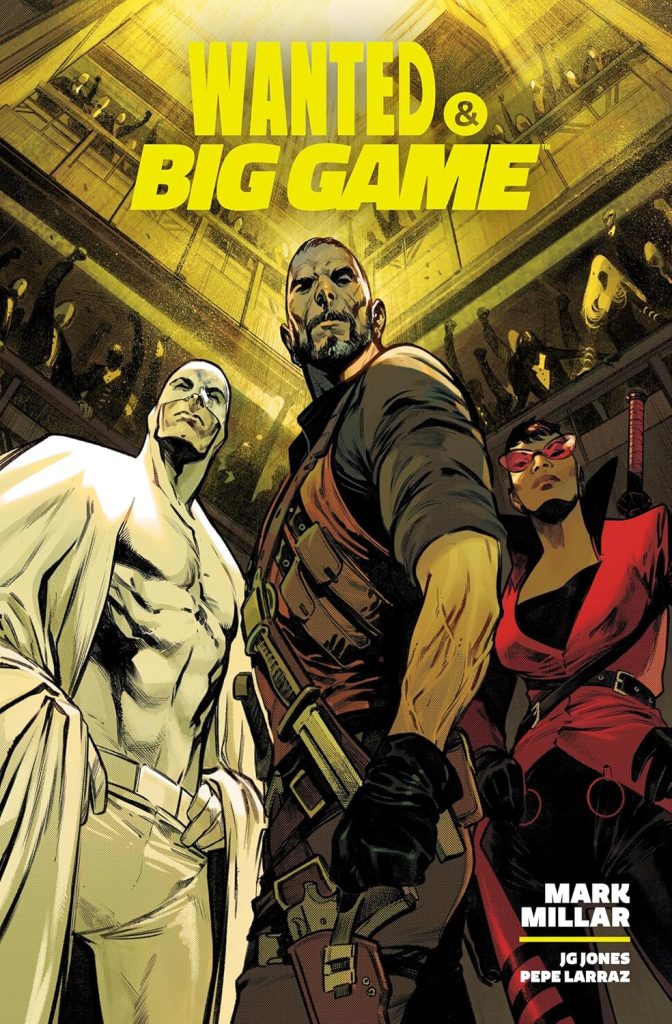

Wanted & Big Game combines two Mark Millar thrillers featuring Wesley Gibson, the first being his rise arc, and while he’s not the focus of the second, he sets events in motion.

Wanted was the first Millar project to be filmed, with very acceptable results, but the comic version is better for having no budgetary constraints. Instead of being surrounded by menacing people in more or less ordinary clothing, J.G. Jones surrounds Wesley with the full super power diaspora. The prospect dangled before Wesley is that he can have so much more than everyone else in life, but in order to claim it he must reject any ethical principles and concerns for others. The father that deserted him in infancy was the world’s pre-eminent hitman, and he’ll inherit his father’s vast fortune, but only if he’s able to convince his father’s colleagues that he can transform from put-upon pawn to someone strong enough to carve his own destiny.

Propelling a first rate plot, Millar and Jones revel in Wesley becoming utterly despicable in a series of events the faint-hearted should avoid. It’s deliberately provocative and offensive from start to finish in a biting the hand that feeds fashion as it lays into superhero culture. Innocents die, the slightly wayward are judged and condemned, and your youth is trampled in the dirt as Millar spurts out every resentment he’s stored since his early childhood. It’s puerile, fantastic and an orgasmic catharsis for writer and reader. Better still, it’s drawn by Jones as if a classic superhero story.

Wesley has come a long way by the time the sequel begins. The original story stood alone, but a sharp bit of plotting pulls Wesley and his companions into the world occupied by all Millar’s subsequent projects, which is an exciting prospect. These have been so disparate in style that there’s considerable ambition to connecting them all together, but Millar pulls that off, incorporating the fantasy of Empress, the supernatural stylings of The Magic Order, and even lighthearted galactic bounty hunter Sharkey alongside the standard superheroes, such as The Ambassadors and Kick-Ass. In fact use of the latter, seen now in his early thirties, is one of the finer moments.

Pepe Larraz is very different artist to Jones, not least out of necessity as he has to feature dozens more characters, and so often on a single page. He opts for a loose style, defining what’s necessary, but expressionistically with frequent use of shadow and bursts of colour instead of background detail. It means that artistically, this combination is very much a game of two halves.

There’s a base level enjoyment to Big Game, but no more. It ticks boxes and pulls the plots together, but never surprisingly. Readers with a broad knowledge of Millar’s projects are going to figure out how a dire situation will be resolved, but there was a time when Millar was well ahead of his readers.