Review by Fiona Jerome

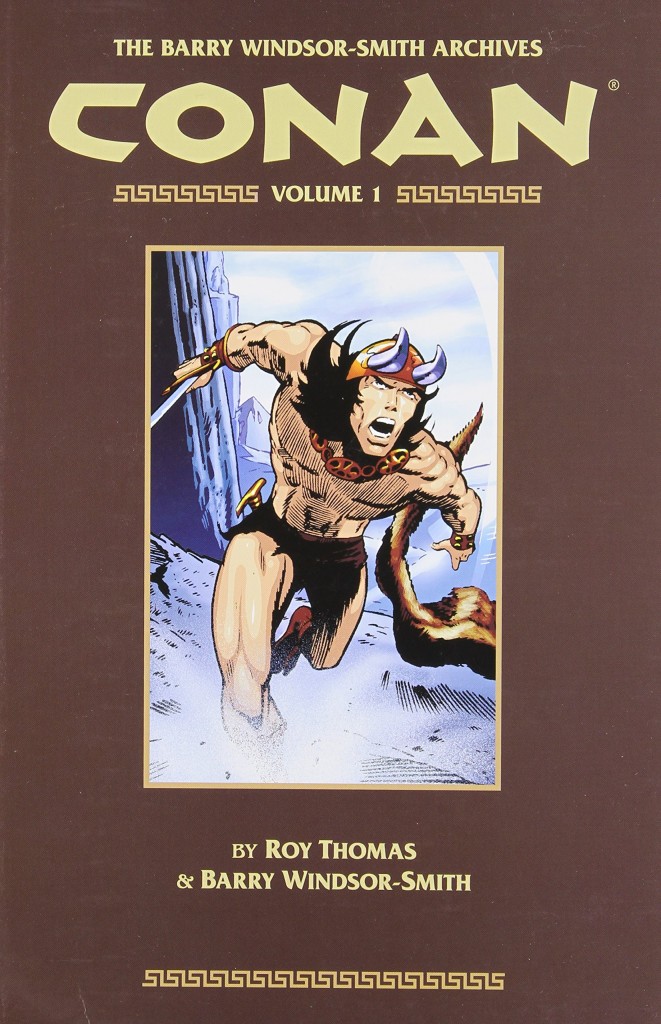

Back in 1970 Roy Thomas had begun fulfilling one of his great dreams by writing the comic version of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories, and plain old Barry Smith was a young British artist attracted to the freshness and dynamism of telling stories through comics. Their coming together for several years to produce Marvel’s Conan comic was greeted as a miracle.

Thomas was a massive Howard enthusiast who would mine the author’s works for many years, incorporating scraps and stories of other heroes into the Conan mythos to feed the seemingly-endless desire for more Conan comics. Thomas took the best elements of the existing Conan stories and gave them a dynamism only comics could really carry off. Oily biceps and furry nappies on film don’t come off, whereas comics add just enough visual excitement to really ignite the prose reader’s imagination. Thomas was a reverent and well-read storyteller, and in Barry Smith he found someone willing to embrace the romanticism of his vision of the young warrior still finding his feet, steered by an innate sense of chivalry and a burning desire to survive at all costs. Smith’s version of Conan’s world was lush and ornate, with decadent cities and crystalline wildernesses.

At first Smith was heavily influenced by classic comic artists, most notably Jack Kirby (and if you’re going to be influenced by any one of the old guard Kirby is surely the one to choose). In his first stories you can see his devotion to Kirby tussling with his desire to bring what he had learned from fine art to the medium, with his interest in British art and illustration just starting to seep through. Much has been made of his influences from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, largely because of the style of his later poster work, but he’s also heavily indebted to a number of English and European illustrators from Beardsley through to Mucha and this element went from strength to strength as he drew more stories.

Smith’s art starts off very dynamic, if a little dodgy when it comes to anatomy; his distortions of the human body don’t seem to come, like Kirby’s, from a desire to create visual tension when depicting action, but more from a clumsiness in drawing bodies. But it rapidly becomes fine lined and ornate, with lots of patterning, not just in background, ornaments and fabrics, but even in how Conan’s hair is drawn as individual, flowing strands. Rarely has barbaric fury looked so decorative, yet as images they work. The place they fall down is in storytelling. Sadly for all the beautiful individual panels, Smith’s storytelling is disjointed, his angles often seemingly chosen at random: they look exciting but trying to work out what’s actually going reveals them obviously there for effect.

This collection does reasonable justice to Smith’s artwork, the detail of which was often lost between blobby, garish colours and being printed on newsprint in the originals. Between the covers and attractive sepia-toned packaging you can see how Smith develops rapidly as an artist, but sadly not a storyteller. It’s a great pity because Thomas is on great form, writing ‘Know, O King…’ like he’s Moses coming down from the mountain, and obviously enjoying adapting some of Howard’s best stories, like ‘The Tower of the Elephant’, alongside the more humdrum fare necessary to keep up the Conan chronology.

Volume 2 presents more of the same, but this content is now more easily found in the Epic Collection, The Coming of Conan, or, if you have the money, in the oversized Omnibus The Original Marvel Years.