Review by Frank Plowright

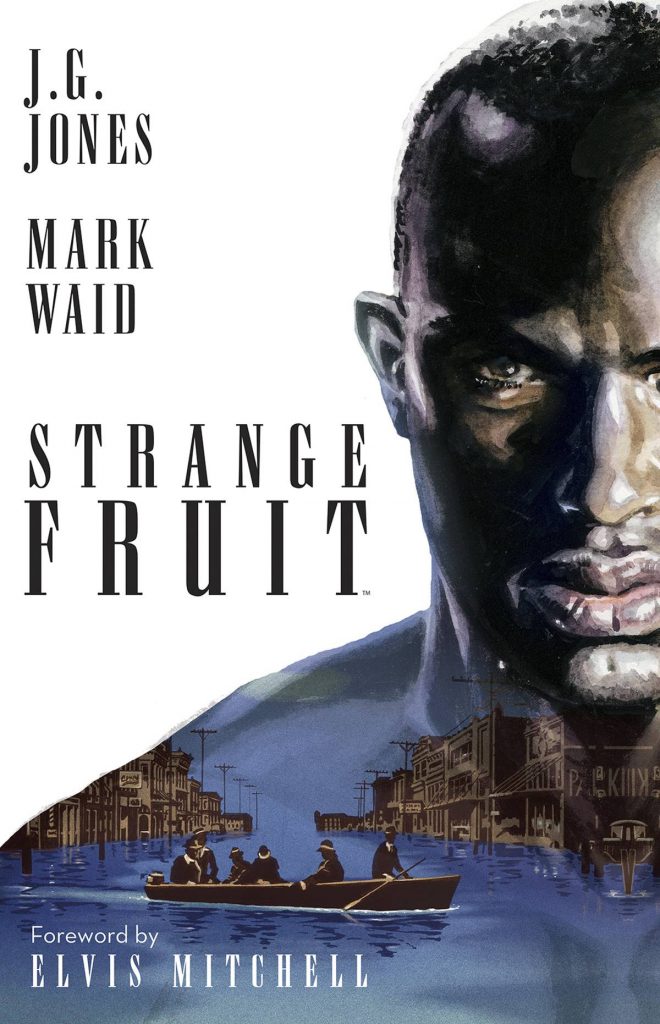

To those who’ve heard the song, Strange Fruit’s title instantly conjures up Billie Holliday’s unforgettable howl against the lynching of African-Americans, first released in 1939. Social activist Abel Meeropol adapted the lyrics from his own 1937 poem when composing the song, and the writing partnership of J. G. Jones and Mark Waid travel ten years further back to Mississippi in 1927 and the floods that blighted the state.

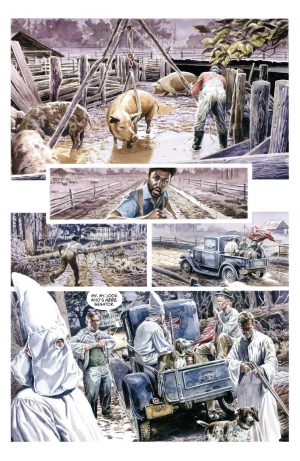

Jones deliberately draws the story in a figurative realism that brings Norman Rockwell to mind. Late in life Rockwell developed a social conscience, but for most of his career gave little thought to how his magnificent illustrations reinforced a comforting picture book form of reality far removed from how life was for the disenfranchised in the USA. Jones delivering scenes in that style is a marker from the start for a sequence showing white farmers attempting to pressgang the local black population into shoring up flood defences.

The disgusting inequalities of time and place are laid on thick over the opening chapter. It would take a bigot not to be uncomfortable, although there may also be some squirming from liberals about the language used. Not to use the terminology surely employed by the Ku Klax Klan to this day would cheapen the story. However, because the cover doesn’t really give much away, it’s only once the scene has been set that the writers kick in with one hell of a surprise. What if there was a black man who didn’t have to worry about Jim Crow laws and the KKK? What if that was because he’s ten feet tall, and an invulnerable alien who’s just arrived on Earth?

He’s given the name Johnson, and becomes a rallying figure in what’s a far more nuanced story than it may first seem. There are white folk in town who consider the KKK ridiculous and while racial tensions remain prominent, the folk of Chatterlee face an even greater threat from flooding. Cleverly, the best possible solution is the most politically inconvenient.

Jones and Waid keep escalating the tensions, and introduce some more to further divide people when their only chance of survival is to unite. It all adds up to a memorable character-based story with some stunning art.

A further comment needs to be made. There’s been online chatter about two white creators producing a story about racial tension using the language of the time, and how that’s apparently unacceptable. As Jones notes in his afterword, no-one else has written this story, so is it better that the wait continues? Really?