Review by Karl Verhoven

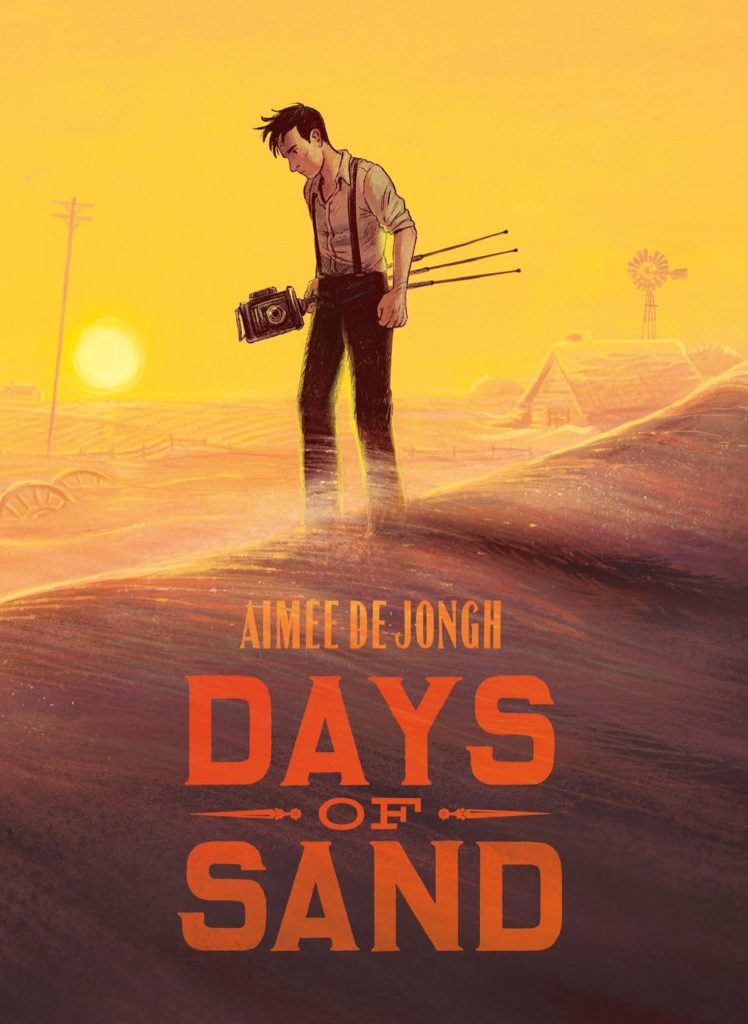

Aimée de Jongh prefaces Days of Sand with photographs of massive dust clouds sweeping over farm buildings in the Mid-West United States during the 1930s. It bestows an immediate realism on her subsequent illustrations, which might otherwise be taken as fictional exaggeration.

Those clouds are seen through the eyes of novice photographer John Clark, assigned by an agency to Oklahoma to document farming communities during the depression years. He’s sent to a drought area known as the Dust Bowl, where the dust is sometimes so dense it blocks out the sunlight. Before heading there de Jongh also draws the Eastern cities of the 1930s, rendering them in attractive detail using the same dulled Earth tones used for the remainder of Days of Sand. In comics such iconography is almost indelibly associated with Will Eisner, but de Jongh relies less on cartooning for similarly evocative results.

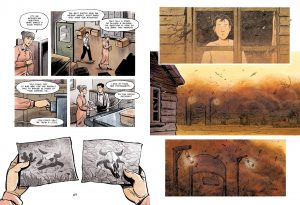

A little too much obvious exposition informs both John and readers what might be expected in Oklahoma and the reasons for it, using large panels over several pages, partially accounting for a story length of over 280 pages. De Jongh is more economical when illustrating the journey there, producing beautiful pages of the changing scenery, and including the “pictures” John takes is a worthwhile touch. The stunning illustration is accompanied by interesting personal observation adding depth, such as “I noticed that sand and dust are very different things. Sand has weight and mass. Its grains will seep through your fingers, one by one… Dust, strangely feels more like water”.

The more John becomes embedded in the Dust Bowl, the more truths he learns, and the ethical compromises he’s been advised to take in order to present a more effective truth sit ever more uneasily in the face of real people and their problems. De Jongh presents a vivid picture of what it’s like to live in an area where plates need to be washed before meals as the dust seeps through everywhere, and how lung disease and resulting death is common. She hangs a tension over Days of Sand by starting with a scene of John burying someone, and then presenting possible candidates as he gradually befriends people.

Days of Sand engages, the art is great, at its best there’s insight and poignancy, John’s realisations are credible, and it should be noted that there are joyful interludes. However, for all the humane fictionalising of hardship and casual death, de Jongh takes the same path as she has John warn about, by becoming too close to her subject and lingering too long. It’s especially true on the extended sequence where someone becomes ill and we learn who John buries. Given what a resonant topic Days of Sand introduces, it might have inspired a great compacted graphic novel, but this is too leisurely and just a good one.

An informative afterword details the history of the organisation employing John, the Farm Security Administration, which did employ photographers to report on conditions for people in remote and troubled areas. A dozen evocative photographs accompany the essay, and more separate the story chapters.