Review by Frank Plowright

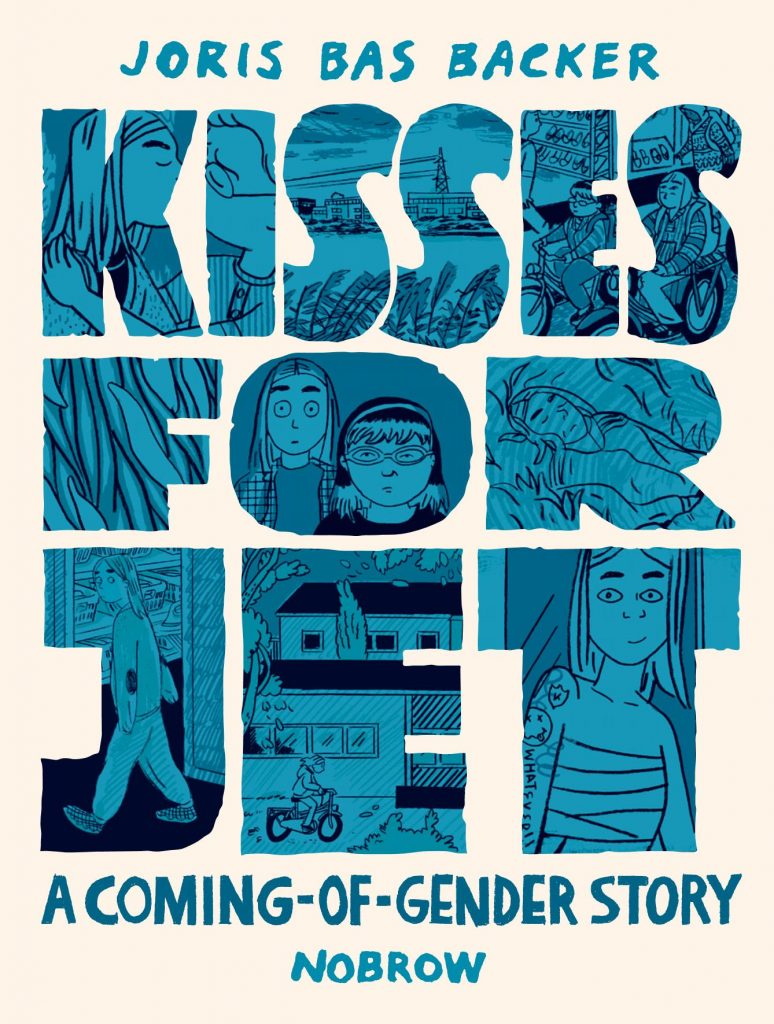

Jet and Sasha first meet in their early teens, both upset at learning of Kurt Cobain’s death. Jet, raised as female, takes a selfie and pastes the head over Cobain’s body, the resulting picture so meaningful it accompanies her when she’s sent with other students to a boarding house in 1999. While not everyone there is tolerant and friendly, an atmosphere of creative freedom prevails, enabling the shy Jet to experiment with identity. Joris Bas Backer has a light touch with the presentation, not spelling everything out in words, but letting the illustrations show how Jet and others are feeling. Sparingly used caption boxes add emotion, as do occasional comments on Jet’s part, such as a defensive response when Sasha raises Jet never wearing tight clothes. Sometimes, though, the visual allegories are just too obvious, such as Jet becoming trapped in a cupboard.

Backer is a tidy cartoonist who fills the panels with detail. The boarding house rooms look lived in, the towns have life, and a changing room looks like a changing room. The same diligence is applied to the cast, their personalities carefully defined, often by what they’re doing rather than what they’re saying. However, his style comes with caveats, and a lapse into a song and dance number at a crucial moment is misjudged, no matter how imaginative and well choreographed.

Both Jet and Sasha are uncomfortable, and one of several interesting connections first has Jet bemoaning that people ought to know what’s she’s feeling, and later there’s a glorious flourishing of just that on Sasha’s part. It turns out Sasha has a pretty good handle on what Jet is going through.

Jet’s uncertainty about identity is mirrored by most of Kisses for Jet being set in 1999, and the social uncertainty about what might happen to computer technology come the millennium, and Backer builds smoothly toward a confluence in the new year. While Jet’s doubts are the primary issue, there’s a narrative necessity to set plots around that, so several other topics are introduced, but Backer just lets them drift. While verité doesn’t demand closure, the musical number removes that explanation, so some consideration for readers regarding issues surrounding supervising staff, for instance, might have been attempted.

Despite a considerable broadening of graphic novel topics in the 21st century, those dealing with gender themes are hardly common, so anyone interested will find plenty to latch on to in Backer’s work. However, although readable and sympathetic, and at times far more, it’s decent enough, but what’s also apparent is how a little more thought could have improved Kisses for Jet.