Review by Frank Plowright

Spoilers in review

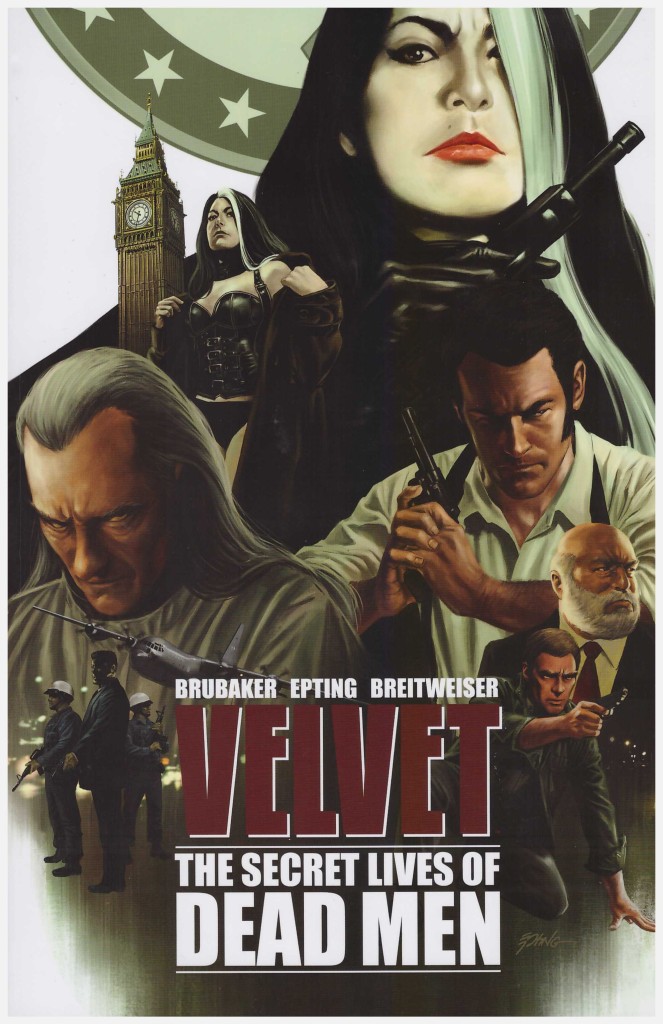

As The Secret Lives of Dead Men continues directly from Before the Living End, how much would it have cost to provide the senile and perpetually addled with a re-cap page? Yet… seeing as that’s the primary criticism of this excellent spy thriller, then perhaps all is well.

Those preferring not to know about events of the first volume, should avoid anything below this paragraph. Steve Epting’s art continues to impress and to evolve. There’s less emphasis on smooth photo-realism here, although he continues to drape his cast in shadows, reflecting their murky occupations. Memorable character design also persists, with a new cast member reminiscent of the viscerally disturbing Bob from Twin Peaks.

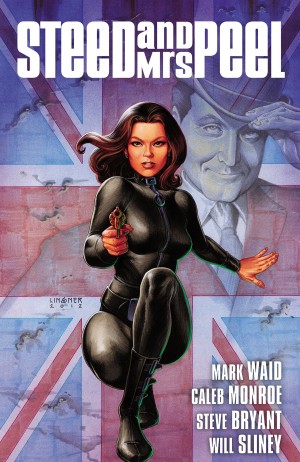

In the preceding book Velvet Templeton was framed in connection with the murder of one current operative and one former operative of Arc-7, a secret agency that carries out assassinations to keep the world safe. In 1973, when the present-day sequences are set, Velvet was an office secretary, yet her past was as an agent, stretching back to the 1950s. She has many contacts, is extremely resourceful, and a desk job hasn’t dulled her reactions. Only age differentiates her from Modesty Blaise at this point, and that’s not a bad thing. The conclusion to Before the Living End saw her having discovered, if not the full story, then that its roots extend back far beyond a recent death.

This reduces the likely suspects who may have framed her to four men, all very senior, and all with considerable resources at their disposal. Revealing any of them as compromised is going to be an extremely difficult, and possibly fatal exercise. One intriguing element slipped in almost unobtrusively, is that Arc-7, the covert agency so far presumed to be British is actually an international organisation with a base in London.

There is a departure here as Velvet isn’t the sole focus of every chapter. Roberts is a tenacious and smart agent dedicated to his job, and Cole is a field agent used to considering what might be a false trail and what might be genuine. Both add to the narrative.

When you reach the “To be continued…” message after the tenth chapter leading you out of the book, you realise that Brubaker’s playing a very long game here. It’s been over 200 delightful pages so far, and Velvet’s story concludes in The Man Who Stole the World.