Review by Frank Plowright

Moses Lwanga is a tortured man who turned from Doctor to fighter when confronted with the reality of life in Uganda in 2002. Although he no longer needs the bandages that cover his face for healing reasons, they remain as a means of establishing an identity, but after undergoing a cleansing ceremony in Easy Kill he’s found a form of stability and has remained in the refugee camp where he returned former child solider Paul.

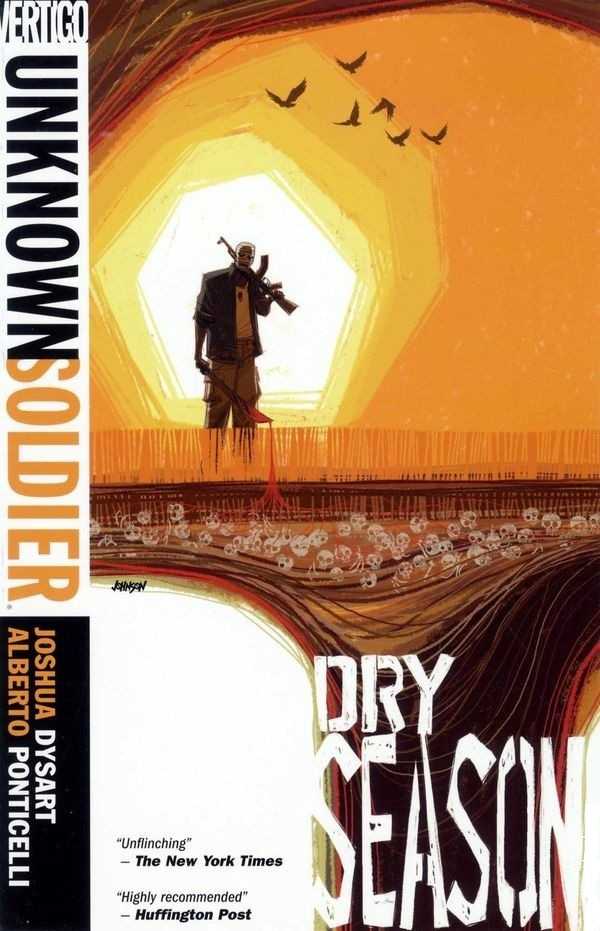

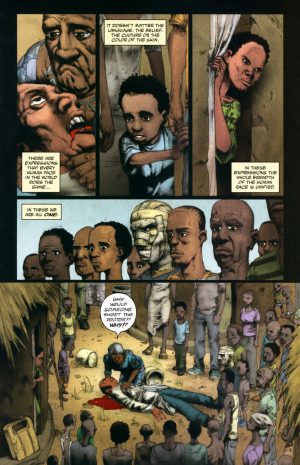

Dry Season looks different because Alberto Ponticelli has changed his artistic method. Instead of using pencils and ink the art he’s painting the pages in watercolour. While the art is good, it’s not as expressive as his previous style, and that coincides with Joshua Dysart’s narrative captions emphasising expressions, which is unfortunate. Otherwise, though, the switch to watercolour is a sensible choice. The ability to draw looser, slightly less defined figures conveys the heat, dust and grime of the refugee camp better than the previous style would. The only other problem is Ponticelli unable to keep Paul looking a consistent age. Over the course of a single page he can vary between child and teenager.

This will be an eye-opening graphic novel for most. Until relatively recently the general assumption has been that while refugee camps might not be comfortable, at least they provide protection and minimal levels of food and water. Dysart’s version of a Ugandan refugee camp in 2002 is near enough a cesspit of simmering resentment, unfounded beliefs and corruption. When the camp’s medicine supply goes missing to coincide with the area’s dry season the difficulties are ramped up. Then someone respected and with influence is killed and Moses finds himself in an unexpected role. Dysart’s admirable commitment to authenticity involves considerable research, and the constant background of deprivation to what’s essentially a mystery story adds a desperate atmosphere. The other tragedy is that the medicine supplied for the needs of the camp, life saving medicine, is to some just another currency, just another way to make money, and Dry Season explains that in distressing detail.

Toward the end, Dysart takes a strange turn. In earlier volumes Moses has heard a festering, poisonous voice in his head, one that revels in action and killing, but since undergoing the cleansing ritual it’s no longer prominent, although Moses feels a presence. It’s a major factor in the conclusion, interesting and frightening, but not necessarily credible. A final chapter has a Western feel about it, which is an interesting achievement given what Unknown Solider is, and leads into the series conclusion found in Beautiful World.

Despite the minor quibbles noted above, this version of Unknown Soldier remains a passion-driven series confronting readers with the appalling combination of genocide and apathy, while also being compulsively readable.