Review by Karl Verhoven

The Walking Dead has become such a phenomenal success that’s it’s quite the sobering experience to revisit the origins. These were as a black and white comic of which there were no great expectations other than the hope the creators that it might break even.

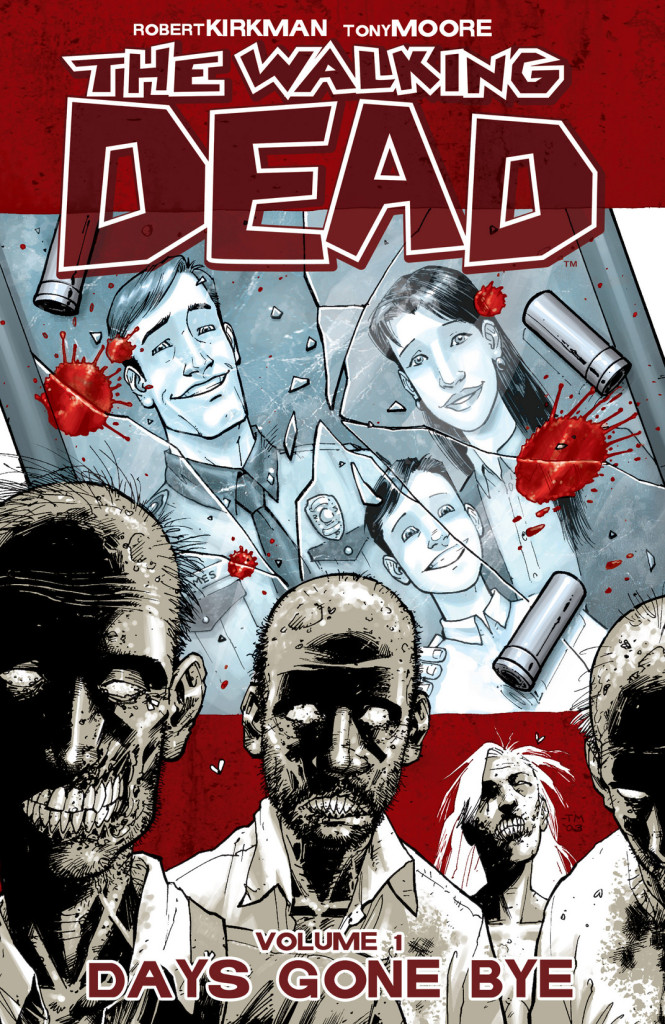

With many never aware that the TV show was adapted from a series of graphic novels, it’s astonishing to see how much of Days Gone Bye transferred directly to the TV screen – most of it, in fact. Both versions open with Officer Rick Grimes awakening alone in hospital unaware of how much the world has changed while he was comatose, recovering from injury sustained in the line of duty.

Tony Moore’s first scene of the zombie infestation is chillingly gruesome, and we should be thankful the pages are black and white. It won’t be the last time in the series such thanks are due. Moore’s work has a cartoon quality lacking in his successor Charlie Adlard’s more naturalistic portrayals of humanity, but this does nothing to draw the sting from those first zombies chewing on remains in the hospital lobby.

Grimes adapts rapidly to the new world, bringing his police training to bear in unexpected situations and learning about zombies from those humans who’ve survived. “No, leave him be”, Grimes is advised, about to shoot a zombie through a fence, “It can’t get to us in here. You may need that bullet later.” It helps that Grimes is able to access the local police station’s weapons cache.

Robert Kirkman at that point was a relatively unknown writer, but an indication of his advanced narrative instincts is provided by the use to which Grimes does put that bullet. He surprises on several other occasions, not least by providing Grimes a rapid happy reunion with his wife and son, located as part of an encampment just outside Atlanta. They were ferried there by his also surviving police partner Shane Walsh.

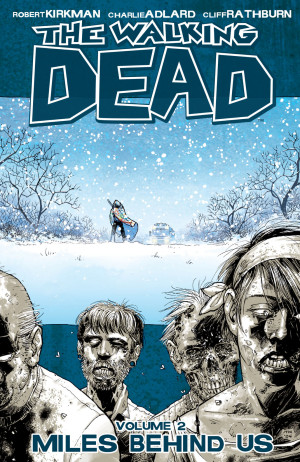

The other members of this small commune are an eccentric bunch that may as well have neon arrows with ‘cannon fodder’ lettering hovering above their heads, but Kirkman surprises again, establishing a largely likeable cast. This is because for all the danger of the environment and the occasional terrifying scenes, he’s primarily writing a soap opera. Grimes’ world may appear to have been rapidly restored, but there are emotional schisms that only escalate in the following Miles Behind Us. And that’s after a shocking ending here.

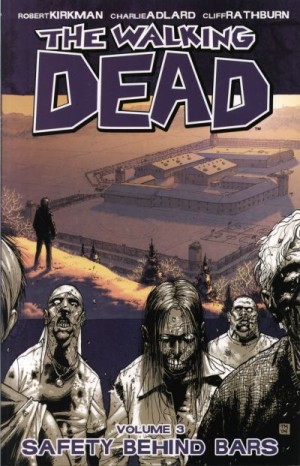

Kirkman supplies an extremely balanced cast, and it would be interesting to know the percentages of instinct and contrivance. They blend ages and races, while at this stage gender orientation isn’t an issue. Has there ever been a gay zombie story? Each cast member has a background to relate, and by the end of the book the group have an awareness of how long it takes to become a zombie following infection, and techniques permitting safe passage among them.

For all the deft construction, anyone who’s not previously experienced The Walking Dead and feels it’s the type of material that will appeal to them is better advised to bite the bullet – never know when you might need it – and shamble in the direction of the first Walking Dead Compendium. It compiles the first eight volumes of the series into well over a thousand pages of life lived on the edge.

Success, however, breeds multiple formats, so the material here can also be found with the next three books as volume one of The Walking Dead Omnibus, and with Miles Behind Us as The Walking Dead: Book One, also in hardcover.