Review by Frank Plowright

Road to Perdition was adapted into an acclaimed and popular film starring Tom Hanks, deliberately cast against type as the 1930s hitman whose activities are the subject to the nostalgic glow of hindsight as narrated by his son when an adult.

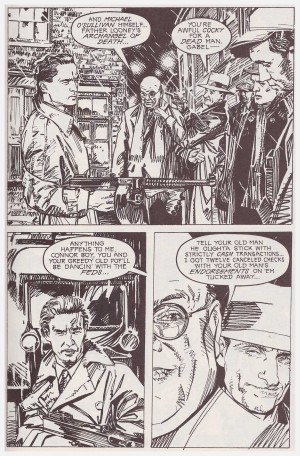

As good as the film might be, it still pales in comparison with the story’s original form, which offers a far richer experience. The creative team are excellent in setting the scene in the opening pages, describing life in Illinois’ Rock Island under the control of gangsters. Max Allan Collins supplies the spartan narrative captions while Richard Piers Rayner provides the accompanying snapshots, heavily photo referenced, bringing to mind the turn of the 20th century illustrators. Rayner never short-changes, but of necessity this work-heavy style diminishes, while making a fine introduction.

Collins constructs a brilliantly conflicting portrait of Michael O’Sullivan. His son’s adoring narrative speaks of a kindly family man, yet we also see him killing without remorse on the instructions of the Looney family (modified in the film to Rooney). O’Sullivan is everything we see, and everything we hear. Feared as a hitman known as the Angel of Death, he’s an honourable man who considers himself a soldier in service to the Looney family. When they betray him, though, he becomes an Angel of Vengeance.

The title stems from the cross-country journey O’Sullivan takes with his son Michael Jr, whom he intends to deposit with relatives in Perdition, Kansas, before going about his business. It doesn’t quite work out that way. Collins intercuts the first hand experiences of Michael Jr with events he’s pieced together later in life from the accounts of historians, filtering through the hyperbole to impart an air of realism. It’s a transformative period for him, as Collins scripts his father executing a methodical retribution.

Rayner casts his characters. O’Sullivan resembles Val Kilmer much of the time, for instance, and other faces may be familiar. Around the midway point there’s an extensive gunfight slaughter sequence. It’s sadly absent from the more introspective film, yet Rayner’s depiction of this provides all the spectacle of cinema, while during the many suspenseful conversation scenes he’s disciplined and true to the script. It’s first rate art.

It’s not only O’Sullivan who has an old-fashioned sense of moral justice, as that extends to the script also. There’s a price to be paid throughout for transgressions, a price that hypocritical trips to the confessional doesn’t wipe out. Collins provides a very satisfying and enthralling read to the end and a final neat twist on fatherhood.

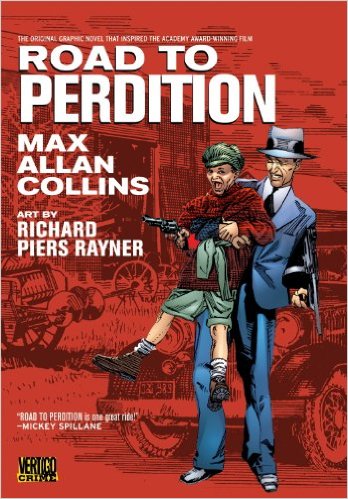

The cover image is strange, yet presumably approved by Collins, depicting O’Sullivan and son seemingly embracing gangster culture together. It’s odd as it flies in the face of what’s reinforced inside where O’Sullivan attaches no trivial allure to his trade, and exhorts his son not to follow in his footsteps.

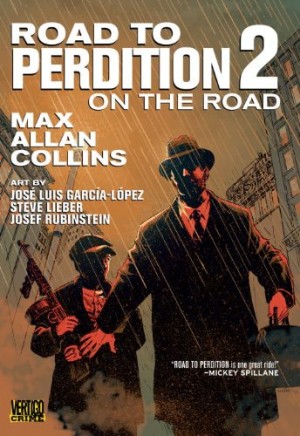

Road to Perdition was later expanded by three slimmer volumes, which are now collected as Road to Perdition 2: On the Road. Both have now been added to Vertigo’s crime list, having previously extended the life of DC’s otherwise short-lived Paradox Press imprint by several years.