Review by Graham Johnstone

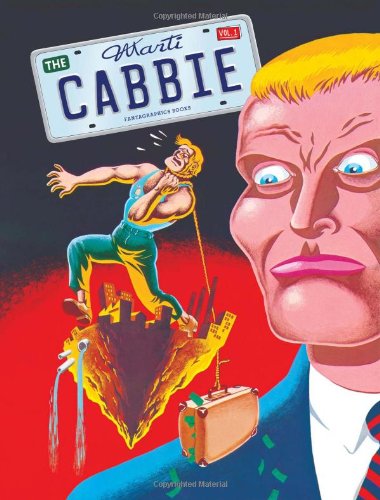

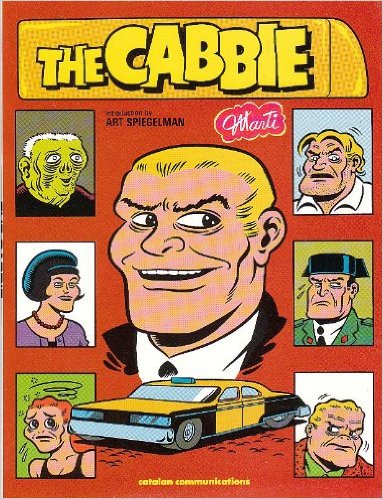

Finally again available in English, The Cabbie is Catalan Marti Riera’s twisted riff on the Dick Tracy newspaper strip.

The protagonist of this book lives his job: so much so that his own sister, reunited with him at their mother’s funeral, calls him Cabbie. He’s passionately religious, and at the start of the book lives with his mother, with his father’s coffined corpse in the back room.

The story begins outside a casino, where John, a desperate man, spots a patron looking “too happy to have lost” get into a cab. Seeking to relieve him of his winnings, he follows on a motorbike. At the first opportunity he jumps into the cab – threatening passenger and driver with a knife, but this is the wrong cab to invade. Primed for such a situation, Cabbie activates the security screen, trapping his assailant’s knife arm, before climbing into the back to administer a savage beating.

As the feud continues, their paths cross and recross, and we learn more about the depredations and struggles of each man’s family. The plot then becomes too implausible and too dark, withstanding further summary. It feels gratuitous and in parts it’s beyond uncomfortable to read. Although he would consider himself pious, Cabbie is hardly any more moral than the Petersons, who at least care about each other and are trying improve their squalid circumstances. Their conflict brings massive cost for each.

Anyone familiar with Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, will recognise both the premise, and the protagonist’s worldview. Marti himself has been upfront about this. Yet in the film the troubled protagonist finds a route to redemption. Cabbie only reaches anxiety – he sees his own suffering, but shows no remorse or contrition. The darkness is perhaps mitigated by the unreality. Cabbie seems set in the past, even an unreal time and place, that and the stylised depiction, slightly distances us from the cruel and ugly events.

Marti’s art style is a consummate homage to Chester Gould’s diagrammatic and forensically detailed work on Dick Tracy. It has the paraphernalia of Gould: the grotesquely caricatured faces, the cars, guns, ladders, rooftops, and zoomed in details. Yet Marti modernises Gould’s style. The loose fluid brushstrokes are replaced by tidy, exact lines, hiding their origins in the human hand. He sticks to the palette of black, white, lines, and only minimal hatching, but Marti’s hatched lines don’t try to fool the eye that they’re shades or depth. They assert their identity as lines on paper, part of an almost systematic visual language.

There’s amazing detail and exactitude, as for example a panel on page 12 when John’s mugshot is taken. The bellows camera and tripod are rendered in plain, mechanical lines, yet with stunning accuracy. It even has John’s image reflected upside down on the viewfinder, and a hand pressing the cable release – caught in the instant of taking the shot. All this is in a two by three inch panel. It would merit being printed bigger, but the small size is true to how Gould’s dense newspaper strips would have appeared.

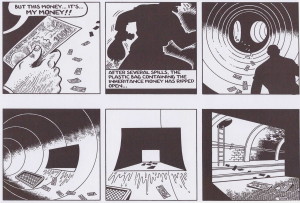

The climactic chase sequence is absolutely gripping, and the sequence in the sewers is a minor masterpiece of design, clarity and economy. That on it’s own would make this book worth having.

If you’ve got the stomach, there’s a thrilling pace to this, and a powerful mastery of the language of comics. Marti may even better Chester Gould.

This is a new translation, but some material was printed by Catalan in the 1980s. At time of writing, the delayed volume two was heading to the presses for release in late 2015.