Review by Frank Plowright

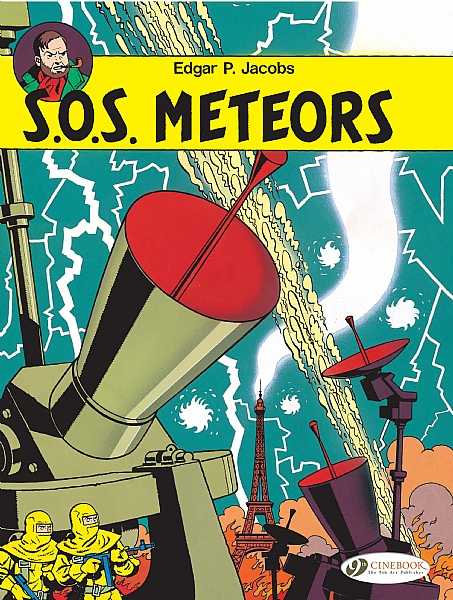

Edgar P. Jacobs was well ahead of the curve in 1959 when he produced this tale of devastation caused by unseasonable climate conditions. If ever there was an example of not judging a book by its cover, though, this is it. The illustration of fantastic machines in the vicinity of the Eiffel Tower, men in radiation suits and the title collectively point to an all-action science fiction blockbuster. While the cover elements have a place, the bulk of S.O.S. Meteors is procedural mystery, and it’s the nearest Jacobs came to duplicating the Tintin books on which he cut his artistic teeth.

Professor Mortimer leaves Paris where incessant rain has compromised the flow of traffic, only to discover the situation is far more precarious in rural areas. He experiences quite the adventure before reaching his destination, and puzzled by the details he decides to investigate the following morning. This is all superbly rendered by Jacobs, from the rain-soaked Parisian streets and the vehicles on them, to the perils of the countryside.

Mortimer also finds it strange that the deranged atmospheric patterns only appear to be affecting Western Europe. Fantastic as it may sound, it’s almost as if the weather is being controlled! The use of poor weather throughout is a fine plot device effectively illustrated by Jacobs, and worked well into several scenes.

The plot splits conveniently into two parts and an ending. Mortimer’s investigations occupy the first half, before we switch to Blake. Rather neatly, it’s not until the final page that they’re actually in each other’s company.

This is a problematical book. Even accepting Jacobs’ notorious word count as given, the plot is meandering and padded, and certain elements have all the subtlety of a punch to the face. The opening sections with Mortimer are the finest, when a considerable mystery requires a peripatetic investigation, and he’s in strange territory with only his wits and instinct to rely on. Almost as good is a ten page chase sequence involving Blake, which is thrilling, yet delivered in an understated fashion by Jacobs.

The final quarter of the book, though, is dull, and the understatement, so effective elsewhere, is maintained in a sequence crying out for more than a couple of panels of widescreen action. It’s here that Jacobs is at his most verbose, and it’s further hampered by both an insight that surely would have come sooner and a clumsy scene foreshadowing a pivotal plot element. When that comes into play it’s beyond belief that the resulting danger is instigated via a mechanism that could easily be activated by chance or accident. Furthermore, regular Blake and Mortimer readers won’t be at all surprised by the identity of the criminal mastermind behind everything. Their overuse is another weakness.

There’s an inherent frustration in assessing the work of Edgar P. Jacobs. He’s revered in Europe, and in Blake and Mortimer he created characters with an appeal spanning decades. His artwork is wonderful and each of his books has some magnificent moments, but many are also fatally flawed. Perhaps Europeans have a greater natural tolerance for imperfection. Jacobs’ version of Blake and Mortimer peaked with The Yellow “M”.