Review by Frank Plowright

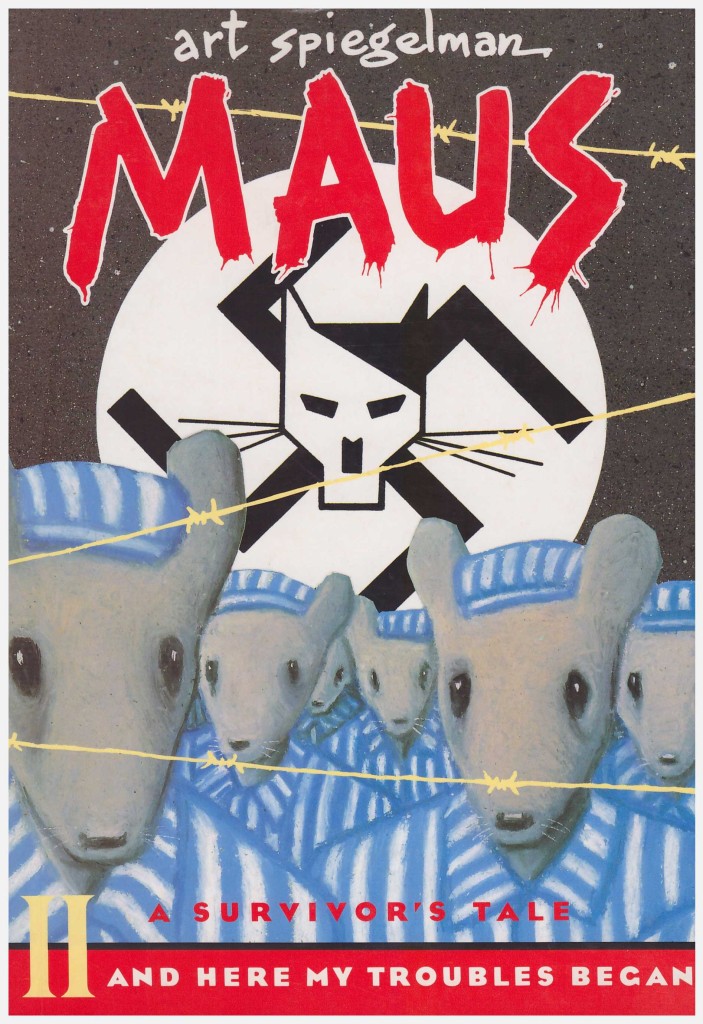

Now available for many years as a collected edition, when first published, Maus spread over two volumes. The end of the previous book saw Vladek Spiegelman arriving at the gates of Auschwitz in 1944, and Art Spiegelman in the early 1980s berating his father for the destruction of Vladek’s wife’s diaries. There’s an early insight into the irritating and selfish nature of the 1980s Vladek. When on holiday Art and his wife receive a message that he’s phoned saying he’s had a heart attack. There’s no truth to this claim, but it’s a ruse used to ensure the call would be returned. The real problem is that his second wife has left him after clearing out their bank account. The first book related her frequent complaints that Vladek never provided enough money to cover basics despite not being short, and gave ample examples of his nature.

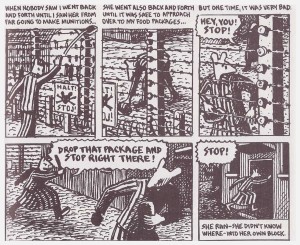

By 1944 European Jews were aware that their lifespan wasn’t measured in years within Auschwitz. One of Vladek’s friends was walking beside him when a guard grabbed his cap, threw it a short distance away and ordered him to retrieve it. As Mandelbaum ran in the opposite direction from the remainder of the group the guard shot him dead, and earned a few extra days holiday for preventing a prisoner from escaping. Such random deaths weren’t rare, but it was for the more systematic extermination that the camp was feared, and there was no escaping the knowledge of what occurred. Vladek’s eventual survival was due to good fortune, others looking out for him, and a capacity to keep his head down, although there are several terrifying moments depicted.

Maus is every bit as good as its reputation suggests, and that reputation has now been sustained over thirty years. The subject matter had never been previously attempted in comics form, and it applies a consistent gravitas, but the glue that cements is the present-day interaction between Art and his father.

No-one can exist under such horrific conditions for an extended period while witnessing atrocities on a daily basis without it having some sort of transformative effect. Vladek survived, but not intact, and while his wife Anja’s experiences aren’t recounted in such detail, they had an even more tragic effect on her. As callous and cantankerous as the elder Vladek comes across, there’s a declaration of love toward his wife that with the hindsight of time is profoundly unsettling. Having been freed from Auschwitz he finds a clean concentration camp uniform, puts it on, and has souvenir photographs taken to present to Anja when he returns home.

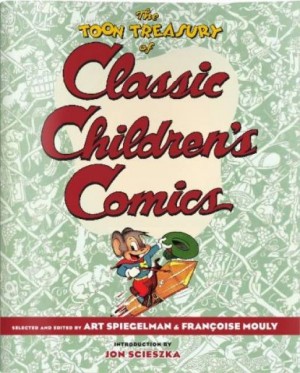

Spiegelman has noted in succeeding years that drawing a comic strip now takes its toll on him, yet here he packs his panels and packs his pages. The metaphorical device of characterising nationalities as animals expires after mice representing jews and cats Germans, but it’s also an efficient artistic shortcut, while the reduction to stereotypes surely intentionally draws some of the sting from the sustained dire circumstances.

Films dealing with the holocaust have had to leaven their narrative with sentimentality, but there’s precious little of that in Maus. It’s stark, it’s terrifying and a story that will be read for decades to come.