Review by Graham Johnstone

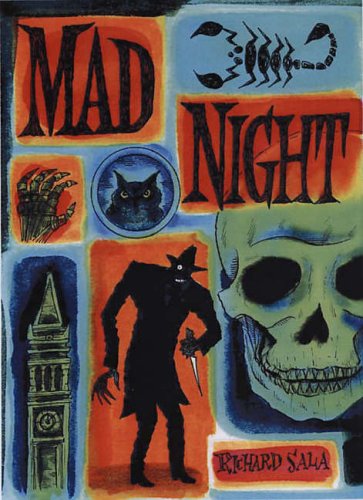

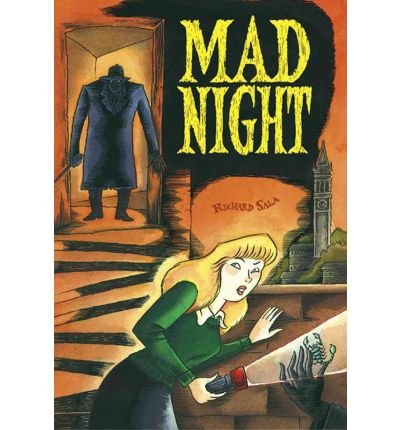

Mad Night collects all twelve issues of Richard Sala’s Evil Eye series. It’s useful to understand these roots, as it makes more sense as a serial than a novel.

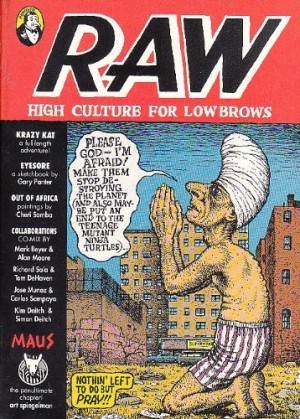

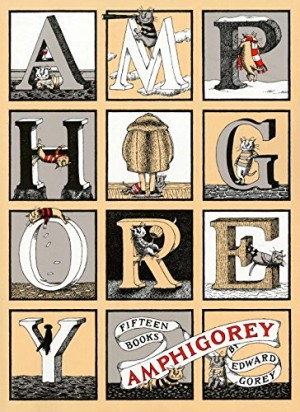

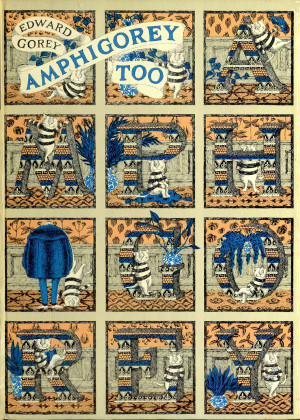

Sala has created a niche for himself with a series of entertaining and stylish books of postmodern gothic. It’s relevant to know that Sala caught many people’s eye in Spiegelman and Mouly’s Raw anthology. In common with other Raw artists like Charles Burns, he combines a genuine and deep love of popular culture, with a critical, ironic, and (politically) liberal twist. Where Burns drew on pulp comics and sci-fi, Sala draws on older gothic traditions, filtered through B-movie horror, Charles Addams, and Edward Gorey.

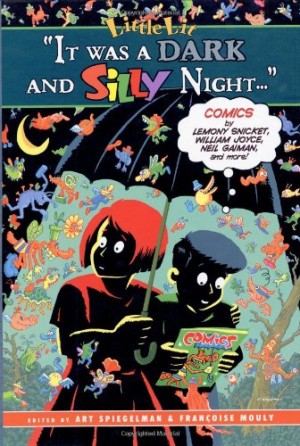

Sala’s tales are probably suitable for those aged ten upwards, who’ll enjoy the adventure and mild horror, although adults will appreciate the wry humour and ironic twists. He’s comics’ nearest equivalent to Lemony Snicket, with whom he collaborated in Little Lit: It was a Dark and Silly Night.

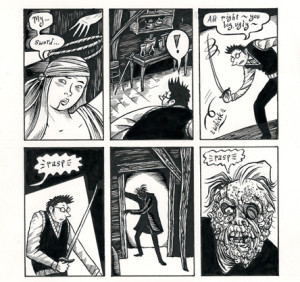

Sala at his best is super concentrated, his pages intricately composed, and precisely rendered. His style is a modern take on old master engravings – a style also used to illustrate gothic fiction. He uses what’s called ‘contour hatching’ where lines used to convey shade, also follow form. Mad Night though, is not quite his best, perhaps the demands of such an extended series required some journeyman satisficing to complete it at a viable pace. The art is here is generally competent, but only occasionally dazzling.

Mad Night is a gothic take on campus fiction. For an American like Sala, their hallowed Universities, often built in the mock medieval, gothic style might seem the most notable remnants of the Old World in the New. Equally, one can imagine arcane, esoteric knowledge and practices surviving there. Tenured professors could have the security, and inbuilt narrow focus to slide into eccentricity and extreme obsession. That’s what seems to have happened here, with the mysterious Ibex, and his colleagues on the science faculty.

Over its two hundred odd pages, the plot is too elaborate to summarise. It’s in any case more about the characters, setting, and general quirky weirdness. Like the detective fiction of Raymond Chandler, the plot is a device to take us through the environment, and take the reader past closed doors. It begins with people needing photographs for different purposes. A stolen camera – a case of mechanical mistaken identity – is the device that sets things in motion.

One of Sala’s subversions of genre tradition is to make a young blonde woman, Judy Drood, the hero instead of the victim. The name recalls the title character of Dickens’ unfinished serial The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and the other characters have similarly Dickensian names. The next most heroic characters are Aunt Azalea’s crew of girl pirates, and the nearest to a male hero, the sheltered Kasper Keene. A dozen colourful characters include bumbling campus cop Officer Pinch, escaped Nazi Herr Schpook, Phleming Lungwort, and scientists Larva, Penumbra and Rhombus.

They pursue their individual agendas, and the story rattles forward entertainingly, with the episode cliffhangers. By the end you’ll probably have forgotten half of what happened at the beginning, but won’t be worrying too much about it. It’s not Sala at his super-distilled best, but it’s an enjoyable romp.