Review by Frank Plowright

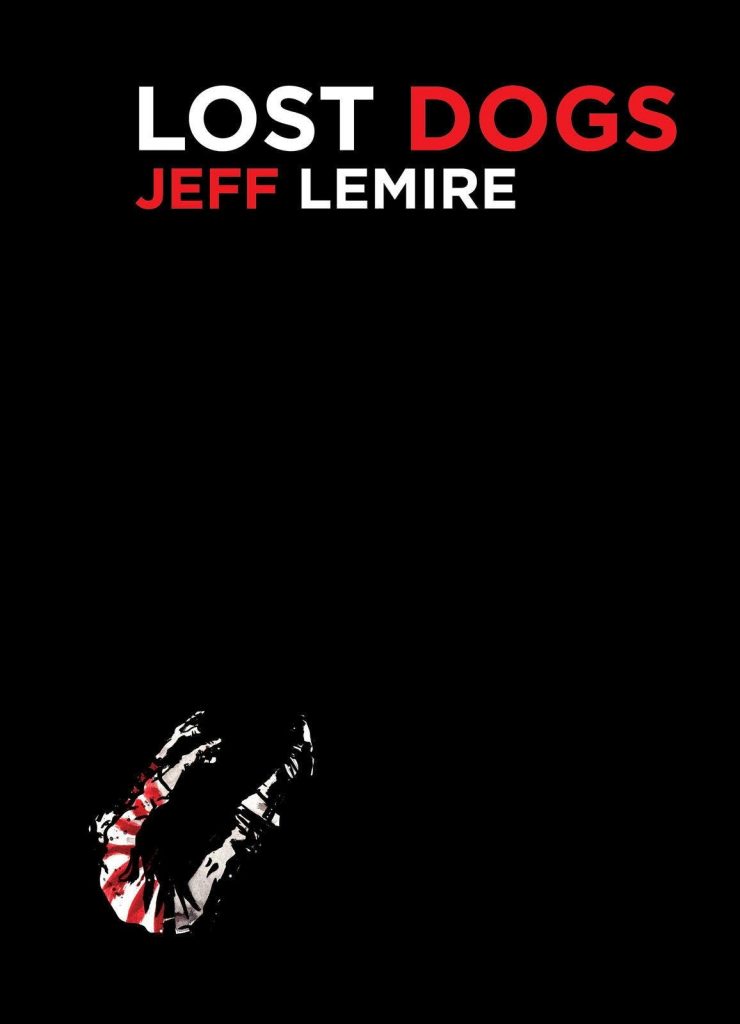

Lost Dogs was a career launching pad for the exceptionally talented Jeff Lemire. A couple of earlier self-published projects earned the award of a Xeric grant to ensure completion of this project, Lemire imprinting his uniqueness with a haunting text and logo-free cover to the original edition. Even the title is relegated to the back cover.

A gentle giant of a protagonist is never named beyond what others call him, and he’s a man of very few words himself. He, his wife and young daughter live a solitary rural existence. The opening pages establish the timeless simplicity of their life, and their daughter is thrilled at the thought of visiting the city the next day. When they do, tragedy occurs.

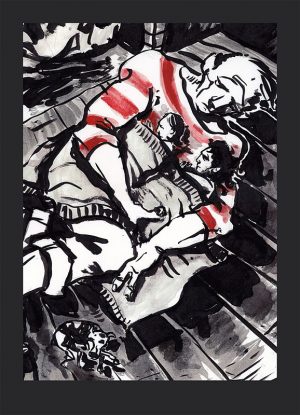

Lemire’s personal projects display a recurring approach to narrative themes and the characters he weaves into them. Those of the isolation of the lost soul, tattered or diminished reputation and a supernatural tenacity are already evident in Lost Dogs. It’s a memorable and tragic work, hinting at what Lemire would later refine without fully displaying it. His art would improve immensely. He still draws the same sort of blocky people, but with more finesse, far fewer lines and less black ink. While there’s a deliberate contrast between the lightness of the countryside and the darkness of the city, there’s also a feeling the ink conveys a lack of total confidence, designed to disguise perceived shortcomings. These are actually more apparent in the layouts, as Lemire hasn’t yet learned how to let his stories breathe, and several sequences of people talking suffer from a rigidity to the page design and the viewpoints to individual panels. Yet there’s an awful lot he does right. The colour is limited to blood and the distinctive red hoops of the protagonist’s shirt, so instantly drawing the eye to any panel in which he features. The craggy, careworn people are far removed from the customary idealisations of comics, and were unlike anything seen even in small run projects in 2005, there’s a viable grubbiness to the period setting, and black pages are a novelty.

The story is relatively simple, yet with elements of redemption, struggle and quest echoing back to Greek myth. The protagonist is separated from his family and left for dead, and the offer of faint hope comes with the price of someone else’s salvation.

Lemire would take immense strides with his following trilogy of Essex County tales for Top Shelf, publishers of Lost Dogs’ second edition in 2012, but this is notable on its own merits as a late 19th century tragedy.