Review by Woodrow Phoenix

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat may be the greatest comic strip ever created. Critics rate Herriman up there with Picasso, Stravinsky and Samuel Beckett for the way he took his medium apart and reassembled it in a unique and brilliantly idiosyncratic form. And just like those avant-garde titans, for every person who hails his work as indisputable genius there are three who just don’t get it and think it’s scratchy nonsense. It’s almost 100 years since Herriman began drawing and writing his masterpiece, supported by publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst who loved the strip so much that he forced all the newspapers he owned to carry it whether the editors liked it or not. This act of extreme patronage kept Krazy Kat alive despite the indifference of the general public who felt (much like many people today) that it was far too intellectually abstruse and just plain weird.

The premise of Krazy Kat is simple. Krazy is besotted with a mouse called Ignatz. Ignatz thinks Krazy is ridiculous and shows his contempt by throwing bricks. Every time Krazy is hit by one of these missiles s/he interprets it as a sign of devotion. Officer Pupp secretly loves Krazy, sees Ignatz for the villain that he is, and tries mostly in vain to prevent Ignatz from striking Krazy with bricks by jailing him. This love triangle structure underpinned stories of astonishingly intricate and baroque variation in daily strips and Sunday pages for almost thirty years. It’s the Sunday pages with their continual variety and invention that Herriman’s reputation rests on, and they are the focus of these reprint volumes from Fantagraphics.

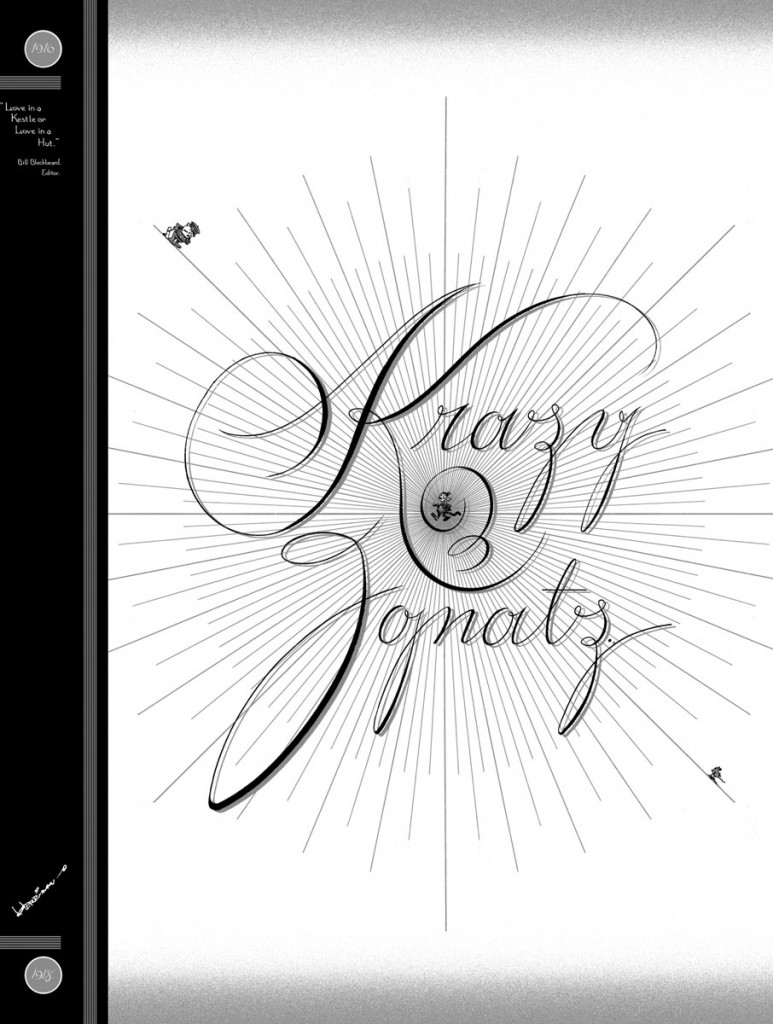

Krazy and Ignatz 1916-1918 features the first two years of Krazy Kat Sunday pages. There’s a great deal of supporting material from editor Bill Blackbeard to help with the context for these strips, including a history/backstory of Krazy’s origins in Herriman’s The Dingbat Family (1910), Baron Mooch (1909) and earlier Herriman strips Lariat Pete, Rosy’s Mama (aka Rosy Posy Grandma’s Girl), Bud Smith, and Zoo Zoo. There is also an “Ignatz Mouse Debaffler Page” which explains the topical references for some of the jokes.

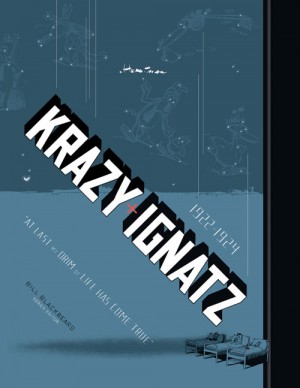

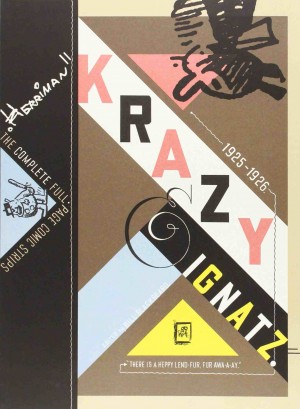

While this is the beginning of Krazy Kat it’s the 11th volume in Fantagraphics’ reprint series. Many publishers have attempted to reissue these strips from the beginning and none of them have managed to publish more than a few years. So when Fantagraphics started this definitive collection of Krazy Kat Sunday pages back in 2002, it began with the 10th and 11th years (1925-1926) because they hadn’t ever been reprinted. After coming to the end, they circled back to the earliest years. This volume and the next two contain references to completing this republishing odyssey, but you can ignore them. There are another twelve Krazy and Ignatz volumes to go before you reach the chronological end of Krazy Kat in 1944.

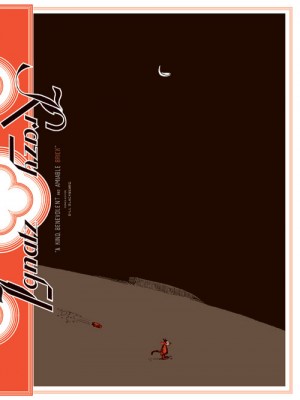

This is the first time the entirety of the 28-year run has been available since originally appearing in newspapers last century. Each large softcover volume has been compiled by the San Francisco Cartoon Art Museum’s Bill Blackbeard, the authority on early 20th Century American comic strips, with the art painstakingly scanned and retouched from original archival tearsheets. The series designer is Jimmy Corrigan author Chris Ware, who has echoed Herriman’s continual experiments with form and designed the covers for each of the thirteen volumes in a completely different style. This is a truly superb packaging and restoration of one of the most highly lauded of all American comics. The best material is yet to come, but these early Sunday pages are already funny, strange and fantastically skilful.