Review by Frank Plowright

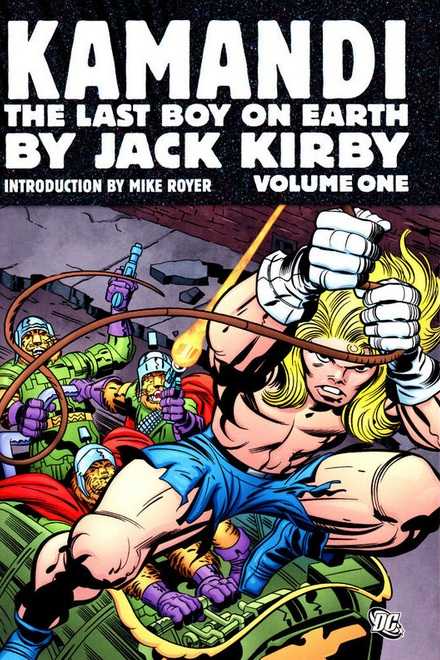

This re-presents material originally available as the first twenty issues of Kamandi’s 1970s comic or Kamandi Archives 1–2. The major difference is the use of modified newsprint paper, which while white, removes the excess vibrancy of the previous editions on gloss stock.

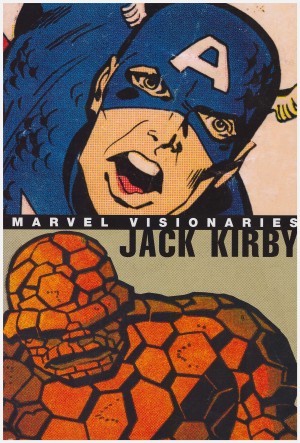

When ageing comic fans gather round the fire to complain about their lumbago, their discussion inevitably leads to Kirby, and consensus would have it that New Gods was his finest work of the 1970s. With its heroic archetypes and updating of themes from classical Greek literature, there’s certainly a case to be made, yet Kamandi could be considered better.

Both titles are characterised by Kirby’s prodigious imagination, but whereas New Gods suffers from his perpetual compulsion to excise his continual ideas, Kamandi is constructed to facilitate that immediacy. He’s among the few intelligent humans left on Earth after a vague catastrophe referred to as ‘The Great Disaster’ has reverted the remainder to near mindless cattle and let animals take their place. Kamandi emerges from the bunker that’s sheltered his forebears through the cataclysm and wanders this new world exploring its wonders. It enabled Kirby to slot a new idea in without consideration of how it affected the bigger picture. So, when he wanted a pause from fighting animals he could return to a theme he always enjoyed, 1920s rod-packing gangsters, or if the idea of Watergate caught his imagination when absorbing the news, that could be incorporated as well. When doing so he transformed what we associate with that name, and developed it instead into the revelation as to how animals came to rule the world.

When asked to create a post-cataclysm comic after DC failed to land the rights to Planet of the Apes, Kirby cast his mind back to a stillborn caveman series he’d created in the 1950s, recycled the design and name of the lead character, and he was away. Kamandi is big screen action reels of an apocalyptic future. Survival is a unifying theme, and Kamandi himself is no passive observer, but a violent, proactive warrior whose continued existence is his most precious commodity.

Kirby’s humanised animals retain the characteristics we associate with them. The big cats and apes are fierce warriors, the snake a devious trader, and the dog loyal to perceived masters. It appears only horses have somehow avoided this evolution, but why pick at that lapse of logic if it permits Kirby to illustrate a charge of mounted tiger cavalry?

Such was his prodigious imagination that Kirby rarely runs a story beyond two chapters, but the one time he does results in the best material here. It’s a rip-roaring, page-turning, ultimately tragic adventure, the plot squirming around like an eel in the fist. It involves a giant monster feared by all who mention it, yet which turns out to be something else entirely, a mad race sequence, a department store that deals in everything available, and the return of some old friends.

Also notable are a two-part tale debating whether it might be better to destroy what Earth has become to permit a clean slate, and the heartbreak of Kamandi setting up home with Flower.

Kirby’s phenomenal art is better for inkers Mike Royer and D. Bruce Berry facilitating the flow rather than attempting polish. It results in a few rough edges, but the sheer kinetic rush compensates. Royer has noted that Kirby equated the content of the comic panel to viewing a movie screen, and that’s very apparent here.

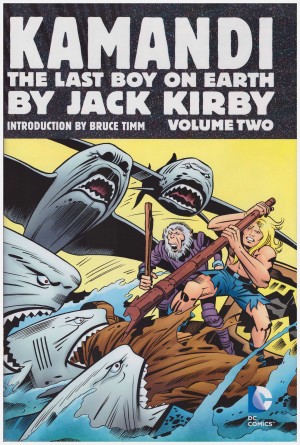

A second volume reprints the remainder of Kirby’s Kamandi. Alternatively his entire run is available in an oversize Omnibus.